History of Toruń

The first settlement in the vicinity of Toruń is dated by archaeologists to 1100 BC (Lusatian culture).[1] During early medieval times, in the 7th through 13th centuries, it was the location of an old Slavonic settlement,[2] at a ford in the Vistula river.

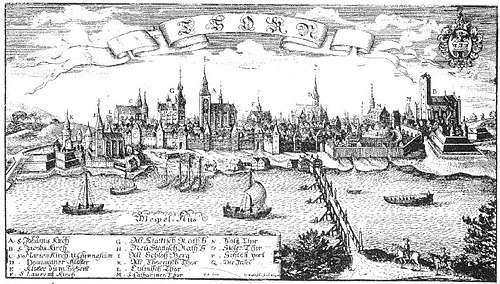

In spring 1231 the Teutonic Knights crossed the river Vistula at the height of Nessau and established a fortress. On 28 December 1233, the Teutonic Knights Hermann von Salza and Hermann Balk,[3] signed the foundation charters for Thorn and Chełmno. The original document was lost in 1244. The set of rights in general is known as Kulm law. In 1236, due to frequent flooding,[4] it was relocated to the present site of the Old Town. In 1239 Franciscan friars settled in the city, followed in 1263 by Dominicans. In 1264 the adjacent New Town was founded predominantly to house Toruń's growing population of craftsmen and artisans. In 1280, the city (or as it was then, both cities) joined the mercantile Hanseatic League, and thus became an important medieval trade centre.

The First Peace of Thorn ending the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War was signed in the city in February 1411. In 1440, the gentry of Thorn formed the Prussian Confederation, and in 1454 rose with the Confederation against the Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, when its delegation submitted a petition to Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon asking him to regain power over Prussia as the rightful ruler. An act of incorporation was signed in Kraków (6 March 1454), recognizing the region, including Toruń, as part[5] of the Polish Kingdom. Those events led to the Thirteen Years' War. After almost 200 years, the New and Old Towns amalgamated in 1454. The Poles destroyed the Teutonic castle. During the war Toruń financially supported the Polish Army. The Thirteen Years' War ended in 1466 with the Second Peace of Thorn, in which the Teutonic Order ceded their control over western provinces, henceforth Royal Prussia. Toruń became part of Kingdom of Poland.

The Polish King granted the town great privileges, similar to those of Gdańsk. In 1501, Polish King John I Albert died in Toruń and his heart was buried in Toruń's St. John's Church. In 1506 Toruń became a royal city of Poland. In 1528, the royal mint started operating in Toruń. A city of great wealth and influence, it enjoyed voting rights during the royal election period.[6] It was also one of four largest cities of Poland.[7] Sejms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were held in Toruń in 1576 and 1626.[8]

In 1557, during the Protestant Reformation, the city adopted Protestantism, while most Polish cities remained Roman Catholic. Under Mayor Henryk Stroband (1586–1609), the city became centralized. Administrative power passed into the hands of the city council. In 1595 Jesuits arrived to promote the Counter-Reformation, taking control of St. John's Church. The Protestant city officials tried to limit the influx of Catholics into the city, as Catholics (Jesuits and Dominican friars) already controlled most of the churches, leaving only St. Mary's to Protestant citizens.

In 1677 the Prussian historian and educator Christoph Hartknoch was invited to be director of the Thorn Gymnasium, a post which he held until his death in 1687. Hartknoch wrote histories of Prussia, including the cities of Royal Prussia.

During the Great Northern War (1700–21), the city was besieged by Swedish troops. The restoration of Augustus the Strong as King of Poland was prepared in the town in the Treaty of Thorn (1709) by Russian Tsar Peter the Great. In the second half of the 17th century, tensions between Catholics and Protestants grew, similarly to religious wars throughout Europe in the previous century. In the early 18th century about 50 percent of the populace, especially the gentry and middle class, were German-speaking Protestants, while the other 50 percent were Polish speaking Roman Catholics.[9] Protestant influence was subsequently pushed back after the Tumult of Thorn of 1724.

In the age of the Polish partitions

In 1793 the Kingdom of Prussia annexed the city following the Second Partition of Poland. In 1807 Napoleon conquered part of the territory and made the city part of the Duchy of Warsaw. It was ruled by King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, but Prussia regained control after Napoleon's defeat in 1814. In 1870 French prisoners of war taken during the Franco-Prussian War were directed to build a chain of forts surrounding the town. The following year the city, along with the rest of Prussia, became part of the new German Empire.

Toruń was part of the area subject to Prussian and later German attempts to Germanise the province. Toruń became a centre of resistance to Germanization and Kulturkampf by Poles, who established a Polish-language newspaper, Gazeta Toruńska.[2] In 1875 a Polish Scientific Society was established, and in 1884 a secret organization dedicated to the restoration of Poland.[2] According to the Treaty of Versailles following World War I in 1919, Toruń was part of the Polish Corridor assigned to Poland. It became the capital of the then-Pomeranian Voivodeship. During Prussian and German rule, especially in the second half of the 19th century, the German authorities promoted ethnic German settlement in the city by falsifying census results. To diminish the number of Poles, one method involved counting all bilingual Poles who spoke German as Germans. Additionally, German soldiers stationed in the city were included in census figures as citizens for propaganda purposes.[10] In order to achieve German majority over Polish population in Toruń, German authorities helped settle large numbers of German officials, workers and craftsmen by legal and administrative means.[11] The number of Germans decreased from 30,509 in 1910 to 2,255 in 1926 and further to 2,057 in 1934.[12] In 1934 the Polish government abrogated the German-Polish treaty of protection of national minorities which was concluded as part of the Versailles treaties granting Poland the Polish corridor.[13]

In 1925, the Baltic Institute was established in the city, and worked on documenting Polish heritage and history in Pomerania. In general, the interwar period was a time of significant urban development in Toruń. Major investments were completed in areas such as transportation (new streets, tramway lines and the Piłsudski Bridge), residential development (many new houses, particularly in Bydgoskie Przedmieście suburb) and public buildings. Following the bridge's construction, in 1938 the nearby town of Podgórz, on the left bank of the Vistula, was incorporated into Toruń.

_2010-07-17_004.jpg)

The Jewish community in Toruń was very active before World War II. Just before the Nazi German invasion of Poland, Jews supported the Polish government fund-raising for Air Defence (Dz.U.R.P.Nr 26, poz. 176) much more generously than average Torunians. The German army entered the city on September 7, 1939. By the end of November the city was declared Judenfrei, with several hundred Jews who chose to stay, deported to the Łódź Ghetto and other locations in the Warthegau.[14] Nazi Germany annexed the city, and administered it as part of Danzig-West Prussia. Poles were classified as Untermenschen by German authorities, with their fate being slave-labor, executions and expulsions.

During World War II, the Germans used the chain of forts surrounding the city as POW camps, known collectively as Stalag XX-A. The city escaped significant destruction during the war. In 1945 it was taken by the Soviet Red Army. The remaining ethnic German population was forcibly expelled, primarily to East Germany, between 1945 and 1947.

After World War II, the population increased more than twofold and industry developed significantly. The founding of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in 1945 was significant. Over the years, it has become one of the best universities in Poland. The university has strongly influenced the intellectual, artistic and cultural life of the city, as well as its perception by non-locals. The university was founded by Polish professors formerly associated with the University of Wilno. After the war, they were forced to move to post-1945 Poland.

| Year | Population | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1768 | approx. 1,000 | |

| 1793 | 5,570 | (cit: Historia Torunia) [15] |

| 1806 | 8,954 | |

| 1815 | 7,095 | |

| 1828 | 11,265 | |

| 1831 | 8,631 | (cit: Preußische Landes 1835) [16] |

| 1864 | 14,106 | without German military: 2,111 [17] |

| 1875 | 18,631 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1880 | 20,617 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1885 | 23,906 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1890 | 27,018 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1900 | 29,635 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1906 | 43,435 | including German military [19] |

| 1910 | 46,227 | (cit: Deutschen Reichs 1903–15) [18] |

| 1931 | 54,280 | (cit: GUS) |

| 1943 | 78,224 | |

| 2009 | 205,934 | (cit: GUS) |

Since 1989, when local and regional self-government was gradually reintroduced and the market economy was introduced, Toruń, like other cities in Poland, has undergone deep social and economic transformations. Locals debate whether the changes have been as successful as they had hoped for, but Toruń has recently reclaimed its strong position as a regional leader, together with Bydgoszcz. Bydgoszcz–Toruń rivalry has existed for centuries.[20][21]

References

- Hypothetical reconstruction of a Lusatian culture settlement, built using bronze age tools: Wola Radziszowska, Poland Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, part of a study by scientists from the Jagiellonian University’s Institute Of Archaeology.

- Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN Warsaw 1976

- "Krzyżacy – założyciele Torunia" (Teutonic Knights — the founders of Thorn). (Internet Archive) Urząd Miasta Torunia. "The foundation charter for Thorn was signed on 28th December 1233 by the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Herman von Salza and the National Master for Prussia and the Slavonic Lands Herman Balka. In that way Thorn was founded by the Teutonic Order and managed by the Knights until 1454." Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- Max Töppen Historisch-comparative Geographie von Preussen: Nach den Quellen, namentlich auch archivalischen, J. Perthes, 1858; PDF

- F. Kiryk, J. Ryś, Wielka Historia polski, t. II, 1320-1506, Kraków 1997, p. 160-161.

- Polska Encyklopedia Szlachecka, t. I, Warsaw 1935, p. 42.

- Maria Bogucka, Miasto i mieszczanin w społeczeństwie Polski nowożytnej XVI-XVIII w., Warsaw 2009

- Władysław Konopczyński, Chronologia sejmów polskich 1493-1793.

- Bahlcke, Joachim (2008). Daniel Ernst Jablonski; Religion, Wissenschaft und Politik um 1700 (in German). p. 227. ISBN 978-3-447-05793-6.

- "Toruń dwóch narodów." Gazeta Miejska Nr 1 (44) z 13 stycznia 2000, Urzad Miasta Torunia (Toruń City Council).

- Lidia Kuchtówna, "Wielkie dni małej sceny," Teatr Narodowy na Pomorzu. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1972, pp. 13 - 204

- Kotowski, Albert S. (1998). Polens Politik gegenüber seiner deutschen Minderheit 1919–1939 (in German). Forschungsstelle Ostmitteleuropa, University of Dortmund. p. 55. ISBN 3-447-03997-3.

- Minderheitenschutzvertrag zwischen den Alliierten und Assoziierten Hauptmächten und Polen

- Maciej Kołyszko (2013). "Zarys historii Torunskiej mniejszosci Żydowskiej (History of Jews in Torun)". Żydzi z Torunia. Cmentarze Żydowskie w Polsce. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- Marian Biskup (ed), Historia Torunia (The History of the City of Toruń), Vol I, II. Instytut Historii (Polska Akademia Nauk). (in Polish)

- August Eduard Preuß: Preußische Landes- und Volkskunde. Königsberg 1835, pp. 413–416, no. 30.

- Steinmnn: Der Kreis Thorn – Statistische Beschreibung, Thorn 1866, p. 47.

- Michael Rademacher: Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte Provinz Westpreußen, Stadt- und Landkreis Thorn (2006).

- Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, 6th edition, Vol. 19, Leipzig and Vienna 1907, p. 501–502.

- Rywalizacja toruńskich "krzyżaków” i bydgoskich "prusaków” trwa pięćset lat!

- Ein Streifzug durch Brombergs Geschichte