Centrohelid

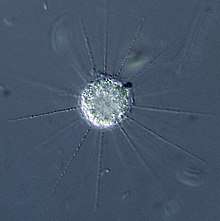

The centrohelids or centroheliozoa are a large group of heliozoan protists.[3] They include both mobile and sessile forms, found in freshwater and marine environments, especially at some depth.

| Centrohelids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Raphidiophrys contractilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Class: | Centrohelea Kuhn 1926 stat. n. Cavalier-Smith 1993 |

| Families[1] | |

|

Raphidiophryidae

| |

| Synonyms | |

Characteristics

Individuals are unicellular and spherical, usually around 30–80 μm in diameter, and covered with long radial axopods, narrow cellular projections that capture food and allow mobile forms to move about.

A few genera have no cell covering, but most have a gelatinous coat holding scales and spines, produced in special deposition vesicles. These may be organic or siliceous and come in various shapes and sizes. For instance, in Raphidiophrys the coat extends along the bases of the axopods, covering them with curved spicules that give them a pine-treeish look, and in Raphidiocystis there are both short cup-shaped spicules and long tubular spicules that are only a little shorter than the axopods. Some other common genera include Heterophrys, Actinocystis, and Oxnerella.

The axopods of centrohelids are supported by microtubules in a triangular-hexagonal array, which arise from a tripartite granule called the centroplast at the center of the cell. Axopods with a similar array occur in gymnosphaerids, which have traditionally been considered centrohelids (though sometimes in a separate order from the others). This was questioned when it was found they have mitochondria with tubular cristae, as do other heliozoa, while in centrohelids the cristae are flat. Although this is no longer considered a very reliable character, on balance gymnosphaerids seem to be a separate group.

Classification

The evolutionary position of the centrohelids is not clear. Structural comparisons with other groups are difficult, in part because no flagella occur among centrohelids, and genetic studies have been more or less inconclusive. Cavalier-Smith has suggested they may be related to the Rhizaria,[4] but for the most part they are left with uncertain relations to other groups. A 2009 paper suggests that they may be related to the cryptophytes and haptophytes (see Cryptomonads-haptophytes assemblage).[5] They are currently classified as Hacrobia, under the Plants+HC clade, although some research studies have found evidence against the monophyly of this group.[6] Centrohelids are currently divided into two orders with contrasting scale morphology and ultrastructure: Pterocystida and Acanthocystida.[1]

- Class Centrohelea Kuhn 1926 stat. n. Cavalier-Smith 1993[7]

- Genus Spiculophrys Zlatogursky 2015

- Order Pterocystida Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Family Choanocystidae Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Genus Choanocystis Penard 1904 non Cognetti 1918

- Family Oxnerellidae Cavalier-Smith & Chao 2012

- Genus Oxnerella Dobell 1917

- Family Heterophryidae Poche 1913

- Genus Heterophrys Archer 1869

- Genus Parasphaerastrum Mikrjukov 1996

- Genus Sphaerastrum Greeff 1873

- Family Pterocystidae Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Genus Chlamydaster Rainer 1968

- Genus Pterocystis Siemensma & Roijackers 1988 non Lohmann 1904

- Genus Raineriophrys Mikrjukov 2001 [Rainierophrys (sic); Raineria Mikrjukov 1999 non Osswald 1928 non de Notaris 1838; Echinocystis Mikrjukov1997 non Haeckel 1896 non Bhatia & Chatterjee 1925 non Torrey & Gray 1840 non Gregory 1897]

- Family Choanocystidae Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Order Acanthocystida Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Suborder Marophryina Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Family Marophryidae Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Genus Marophrys

- Family Marophryidae Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Suborder Chalarothoracina Hertwig & Lesser 1874 stat n. Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Family Raphidiophryidae Mikrjukov 1996 emend. Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Genus Heteroraphidiophrys Mikrjukov & Patterson 2000

- Genus Polyplacocystis Mikrjukov 1996

- Genus Pseudoraphidiophrys Mikrjukov 1997

- Genus Raphidiophrys Archer 1867 [Raphidiaphrys (sic) Greeff 1869]

- Family Acanthocystidae Claus 1874 emend. Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Genus Raphidocystis Penard 1904 [Raphidiocystis (sic) Doflein 1928 ; Rhaphidocystis (sic)]

- Genus Pseudoraphidocystis Mikrjukov 1997 [Pseudoraphidiocystis (sic)]

- Genus Acanthocystis Carter 1863 non Kuehner 1926 non Bather 1889 non Haeckel 1896 nomen nudum

- Family Raphidiophryidae Mikrjukov 1996 emend. Cavalier-Smith & von der Heyden 2007

- Suborder Marophryina Cavalier-Smith 2011

References

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Chao, Ema E. (2012). "Oxnerella micra sp. n. (Oxnerellidae fam. n.), a Tiny Naked Centrohelid, and the Diversity and Evolution of Heliozoa". Protist. 163 (4): 574–601. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.12.005. PMID 22317961.

- Kühn, A. (1926). Morphologie der Tiere in Bildern. Heft 2: Protozoen. Teil 2. Rhizopoden. Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin.

- Nikolaev SI; Berney C; Fahrni JF; et al. (May 2004). "The twilight of Heliozoa and rise of Rhizaria, an emerging supergroup of amoeboid eukaryotes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (21): 8066–8071. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308602101. PMC 419558. PMID 15148395.

- Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE (April 2003). "Molecular phylogeny of centrohelid heliozoa, a novel lineage of bikont eukaryotes that arose by ciliary loss". J. Mol. Evol. 56 (4): 387–396. Bibcode:2003JMolE..56..387C. doi:10.1007/s00239-002-2409-y. PMID 12664159.

- Burki, F; Inagaki, Y; Bråte, J; Archibald, J.; Keeling, P.; Cavalier-Smith, T; Sakaguchi, M; Hashimoto, T; Horak, A; Kumar, S; Klaveness, D; Jakobsen, K.S; Pawlowski, J; Shalchian-Tabrizi, K (2009). "Large-scale phylogenomic analyses reveal that two enigmatic protist lineages, Telonemia and Centroheliozoa, are related to photosynthetic chromalveolates". Genome Biology and Evolution. 1: 231–238. doi:10.1093/gbe/evp022. PMC 2817417. PMID 20333193. Archived from the original (Free full text) on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Zhao, Sen; Burki, Fabien; Bråte, Jon; Keeling, Patrick J.; Klaveness, Dag; Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran (2012). "Collodictyon—An Ancient Lineage in the Tree of Eukaryotes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (6): 1557–68. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss001. PMC 3351787. PMID 22319147.

- "Virae, Prokarya, Protists, Fungi". Collection of genus-group names in a systematic arrangement. Archived from the original on 2016-08-14. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

Further reading

- Patterson DJ (October 1999). "The Diversity of Eukaryotes". Am. Nat. 154 (S4): S96–S124. doi:10.1086/303287. PMID 10527921.