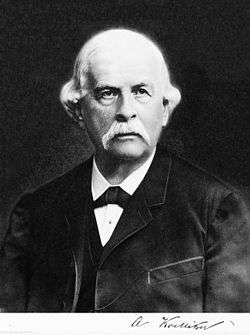

Albert von Kölliker

Albert von Kölliker (born Rudolf Albert Kölliker; 6 July 1817 – 2 November 1905) was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, and histologist.

Rudolf Albert von Kölliker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Rudolf Albert Kölliker 6 July 1817 Zurich, Switzerland |

| Died | 2 November 1905 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | Switzerland |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich University of Bonn University of Berlin |

| Known for | Contributions to zoology |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1897) Linnean Medal (1902) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anatomy, physiology |

| Doctoral advisor | Johannes Peter Müller Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle |

Biography

Albert Kölliker was born in Zurich, Switzerland. His early education was carried on in Zurich, and he entered the university there in 1836. After two years, however, he moved to the University of Bonn, and later to that of Berlin, becoming a pupil of noted physiologists Johannes Peter Müller and of Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle. He graduated in philosophy at Zurich in 1841, and in medicine at Heidelberg in 1842. The first academic post which he held was that of prosector of anatomy under Henle, but his tenure of this office was brief – in 1844 he returned to Zurich University to occupy a chair as professor extraordinary of physiology and comparative anatomy. His stay here was also brief; in 1847 the University of Würzburg, attracted by his rising fame, offered him the post of professor of physiology and of microscopical and comparative anatomy. He accepted the appointment, and at Würzburg he remained thenceforth, refusing all offers tempting him to leave the quiet academic life of the Bavarian town, where he died.[1]

At Zurich, and afterwards at Würzburg, the title of the chair which Kölliker held laid upon him the duty of teaching comparative anatomy. Many of the numerous memoirs which he published, (including the very first paper he wrote) and which appeared in 1841, before he graduated, were on the structure of animals of the most varied kinds. Notable among these were his papers on the Medusae and allied creatures. His activity in this direction led him to make zoological excursions to the Mediterranean Sea and to the coasts of Scotland, as well as to undertake, conjointly with his friend Carl Theodor Ernst von Siebold, the editorship of the Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie, which, founded in 1848, continued under his hands to be one of the most important zoological periodicals.[2]

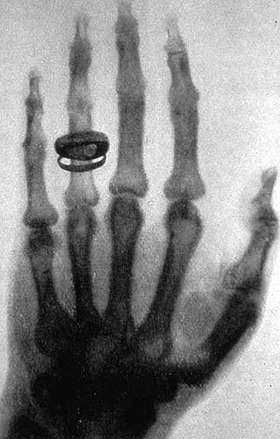

His hand was one of the first to be x-rayed, by his friend Wilhelm Roentgen.[3]

Works

Kölliker made contributions to the study of zoology. His earlier efforts were directed to the invertebrates, and his memoir on the development of cephalopods (which appeared in 1844) is considered a classical work. He soon passed on to the vertebrates, and studied the amphibians and mammalian embryos. He was among the first, if not the very first, to introduce into this branch of biological inquiry the newer microscopic technique – the methods of hardening, sectioning and staining. By doing so, not only was he enabled to make rapid progress himself, but he also placed in the hands of others the means of a similar advancement. The remarkable strides forward which embryology made during the middle and latter half of the 19th century will always be associated with his name. His Lectures on Development, published in 1861, at once became a standard work.[2]

But neither zoology nor embryology furnished Kölliker's chief claim to fame. If he did much for these branches of science, he did still more for histology, the knowledge of the minute structure of the animal tissues. Among his earlier results was the demonstration in 1847 that smooth or unstriated muscle is made up of distinct units, of nucleated muscle cells. In this work, he followed in the footsteps of his master Henle. A few years before this, there was doubt whether arteries had muscle in their walls – in addition, no solid histological basis as yet existed for those views as to the action of the nervous system on the circulation, which were soon to be put forward, and which had such a great influence on the progress of physiology.[2]

Kölliker's contributions to histology were widespread; smooth muscle, striated muscle, skin, bone, teeth, blood vessels and viscera were all investigated by Kölliker, and he touched none of them without discovering new truths. The results at which he arrived were recorded partly in separate memoirs, partly in his great textbook on microscopical anatomy, which first saw the light in 1850, and by which he advanced histology no less than by his own researches.[2]

Albert L. Lehninger asserted that Kölliker was among the first to notice the arrangement of granules in the sarcoplasm of striated muscle over a period of years beginning around 1850. These granules were later called sarcosomes by Retzius in 1890. These sarcosomes have come to be known as the mitochondria-the power houses of the cell. In the words of Lehninger, "Kölliker should also be credited with the first separation of mitochondria from cell structure. In 1888 he teased these granules from insect muscle, in which they are very profuse, found them to swell in water, and showed them to possess a membrane."

In the case of almost every tissue, our present knowledge contains information first discovered by Kölliker – it is for his work on the nervous system that his name is most remembered. As early as 1845, while still at Zurich, he supplied the clear proof that nerve fibers are continuous with nerve cells, and so furnished the absolutely necessary basis for all sound speculations as to the actions of the central nervous system.[2]

From that time onward he continually laboured at the histology of the nervous system, and more especially at the difficult problems presented by the intricate patterns in which nerve fibers and neurons are woven together in the brain and spinal cord. From his early days a master of method, he saw at a glance the value of the new Golgi staining method for the investigation of the central nervous system, and, to the great benefit of science, took up once more in his old age, with the aid of a new means, the studies for which he had done so much in his youth. Kölliker contributed greatly to knowledge of the inner structure of the brain.[2][4] In 1889, he reproduces the histological preparations of the father of neuroscience Ramón y Cajal and confirms the theory of neuronism.

Honors

Kölliker was ennobled by Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria in 1897 and thus permitted to add the predicate "von" to his surname. He was made a member of the learned societies of many countries; in England, which he visited more than once, and where he became well known, the Royal Society made him a fellow in 1860, and in 1897 gave him its highest token of esteem, the Copley medal.[2]

A species of lizard, Hyalosaurus koellikeri, is named in his honor.[5]

Heterogenesis

In 1864 Kölliker revived Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire's theory that evolution proceeds by large steps (saltationism), under the name of heterogenesis.[7] Kölliker was a critic of Darwinism and rejected a universal common ancestor, instead he supported a theory of common descent along separate lines.[8] According to Alexander Vucinich the non-Darwinian evolution theory of Kölliker tied "organic transformism to three general ideas, all contrary to Darwin's view: the multiple origin of living forms, the internal causes of variation, and "sudden leaps" (heterogenesis) in the evolutionary process."[9] Kölliker claimed that heterogenesis functioned according to a general law of evolutionary progress, orthogenesis.[10]

Notes

- Foster 1911, p. 889.

- Foster 1911, p. 890.

- "RÖNTGEN, Wilhelm Conrad (1845-1923). Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen (Vorläufige Mittheilung). -- Eine neue Art von Strahlen. II. Mittheilung. Offprints from: Sitzungsberichte der Würzburger Physik.-medic. Gesellschaft, 1895 [no. 9], and 1896, [nos. 1-2]. Würzburg: Verlag und Druck der Stahel'schen k. Hof.-und Universitäts- Buch- und Kunsthandlung, 1895-1896". www.christies.com. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Handbuch der Gewebelehre des Menschen, t. 2, Leipzig, 1896. (in German).

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Koelliker", p. 144).

- IPNI. Koell.

- Wright, Sewall (1984). Evolution and the Genetics of Populations: Genetics and Biometric Foundations. 1. University of Chicago Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0226910499.

- Di Gregorio, Mario A. (2005). From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 303. ISBN 978-3525569726.

- Vucinich, Alexander (1988). Darwin in Russian Thought. University of California Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0520062832.

- Glick, Thomas F. (1988). The Comparative Reception of Darwinism. University of Chicago Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0226299778.

References

Further reading

- "Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905) Würzburger histologist". JAMA. 206 (9): 2111–2. 1968. doi:10.1001/jama.206.9.2111. PMID 4880509.

- Albert L. Lehninger (1964). "The Mitochondrion". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert von Kölliker. |