Herb farm

An herb farm is usually a farm where herbs are grown for market sale. There is a case for the use of a small farm being dedicated to herb farming as the smaller farm is more efficient in terms of manpower usage and value of the crops on a per acre basis.[1] In addition, the market for herbs is not as large as the more commercial crops, providing the justification for the small-scale herb farm. Herbs may be for culinary, medicinal or aromatic use, and sold fresh-cut or dried.[2][3] Herbs may also be grown for their essential oils or as raw material for making herbal products.[4] Many businesses calling themselves an herb farm sell potted herb plants for home gardens. Some herb farms also have gift shops, classes, and sometimes offer food for sale. In the United States, some herb farms belong to trade associations.

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

Categories

|

|

|

History

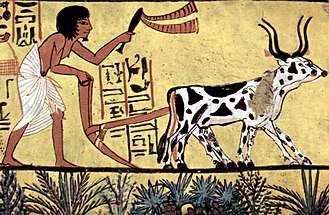

The rise of the herb farm stems from human interactions in agriculture, cultural preferences, growing conditions and availability of certain herbs. In early Egyptian times, herbs were grown for religious ceremonies, temple use, and in mummification,[5] these herbs included: frankincense, myrrh, lotuses, poppies, cornflowers and chamomile. In Islamic cultures, herb gardens are also tied to buildings and are often enclosed behind walls and arranged in geometric patterns that maximize the use of space. Christian monasteries borrowed heavily from this same style and grew their herbs in a similar manner. As these monasteries expanded in influence and Christianity spread, the needs of the garden expanded as a means of creating a self-sufficient monastery. Culturally, these buildings are also associated with healing the sick and emphasis was placed on the growing of medicinal herbs. As cities grew, certain larger houses, and small plots of land were used to expand on the growing of herbs, both for cooking and medicinal properties. Universities began to explore the development of research into medicinal herbs, which required plots of land to be set aside to grow these herbs. In Greek gardens, the herb garden was paired with the bee garden, such that they became fused. The practice of keeping both types of herb farms together was carried over into European and American Colonial gardens.[6]

In the colonial United States (in the time period from 1620-1840)[7] herbs were grown for a variety of purposes, ranging from utilitarian, to vanity gardening. In Puritanical regions herbs were grown based on their functional use in cooking, medicines, and for a source of fragrance. Whereas the established towns the herb garden followed the trends of the time frame, sometimes they were present and other times not.

In rural China, herb growing was also important, and based on the cultural and scientific interests of that region.

Growing process

Soil

Most herbs prefer a well-drained, friable soil. This allows the roots to receive the water they need without the danger of rot and promotes a strong root system.[8] There are a variety of soil amendments to be added if the soil in a specific area is not desirable for to promote good herb growth. For outdoor herb farming the soil must be prepared ahead of time by removing vegetation and analyzing soil for pH value and amount of fertilizer needed for proper growing conditions. In commercial industries, additional soil sterilization is used to eliminate common soil derived crop diseases, pests, and for the control of weeds.[9] Additionally, crop rotation is important to diminish the possibility of common crop diseases.

Greenhouses/nurseries

Greenhouse production allows for year-round growing of herbs, giving a level of control of temperature and water conditions inside of the greenhouse which is a desired outcome for the herb farmer.[10] Other options for the greenhouse allow the grower to start seedlings early and then prepare them for transplant outdoors as the weather permits. The type of greenhouse used for growing depends on the long term needs of the herb farm, and consideration for utility costs should be factored when determining size and type of greenhouse installation necessary. Important factors for growing from the seedling stage to the full cycle of the plant are water, light, temperature control, mineral content of soil, control of the gases required in the process of photosynthesis, and pest and disease management.

Pest and disease control

Options for controlling pests of the herb farm are predator insects and insecticides. Some of the known predatory insects used on the herb farm are: ladybugs, aphid parasites, lacewings, mantids, and predatory mites.[11] Insecticide use depends on the type of pest present on the herb farm. Common pests are aphids, whiteflies, and fungus gnats, each requiring a different type of pesticide and having different levels of difficulty to manage. Environmental management plans for pests include the use of a good insect screen, air movement, and ventilation: methods that reduce the stress on the plant. Common herb diseases are: botrytis, mildew, viruses, rusts, and root disease.[9] Successful management of plant diseases include environmental controls similar to that of the pest management plan. Chemical means are determined based on the type of plant disease present in the herb.[9]

Seeds and cutting/types of propagation

Herb plants can be started from seed or purchased as a seedling. Common herbs grown from seed are basil, flat and curly leaved parsley, chives, dill, sage, thyme, rosemary, cilantro. Herbs can also be grown via vegetative means, rooting cuttings, division of the plant, bulbs, or tissue culture. Rooting cuttings works best with soft stemmed herbs such as mint, lemon balm, basil and stevia. The advantage of growing via a vegetative process gives you a plant that is exactly identical to the parent plant.[10]

Farming systems

Herb farms can range from in-house gardening hobby, mini-farming, and all the way to full-scale commercial operations. Start-up farms are generally smaller and focus on local markets, they can include organic, hydroponic and traditional growing systems. The small farm generally has one or two greenhouses, an area for storage, and an area to sell the product.[12] Commercial operations focus on a larger scale of cash profit and may use some of the same growing systems, but can range vastly in their application of advanced technology and science. There are a variety of hydroponic systems for herb farming as herbs have a smaller root system and can be suited to the different types of hydroponic production.[9] Growing herbs hydroponically is considered to be more efficient, and to produce a higher quality product (pg 17),[9] and can be seen in both the small farm and in commercial operations. In contrast, organic farming systems that additional make use of a greenhouse expand the growing season, is a fast growing niche market, and offers monetary value as a result. Organic certification criteria must be met based on soil content, fertilizer sources, and method of pest control.

Economics

The concept of starting up your own small, herb farms stems from the needs of local restaurants and at-home chefs demanding fresher, locally grown products.[13] Home grown, small scale start ups often begin on a smaller piece of land and may also include areas of the house to be used to germinate seeds.

Herb garden at Kariwak Village in Tobago

Herb garden at Kariwak Village in Tobago Lavender growing on a farm

Lavender growing on a farm

References

- Miller, Richard (1985). The Potential of Herbs as a Cash Crop. Kansas City:MO: Acres U.S.A. p. 6. ISBN 0911311106.

- Traunfeld, Jerry (2000). "The Herbfarm cookbook". New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-83976-8. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- Miller, Richard Alan (2000). "Getting started : important considerations for the herb farmer". Goodwood, Ont.: Richters. Retrieved January 15, 2012. ISBN 1-894021-04-5

- Rogers,Maureen A. (1995). "Herbs: A Small-Scale Agriculture Alternative". USDA's Office for Small-Scale Agriculture. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Bown, Deni (1995). Encyclopedia of Herbs and Their Uses. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 12. ISBN 0789401843.

- Webster, Helen Noyes (1939). Herbs: how to grow them and how to use them. Boston: Hale, Cushman and Flint. pp. 18–19.

- Favretti, Rudy (1972). Colonial Gardens (PDF). Barre Publishers. ISBN 0827172303.

- Gardner, Jo Ann (1997). Living with Herbs: a treasury of useful plants for the home and garden. Woodstock:VT: The Countryman Press. p. 30. ISBN 0881503592.

- Morgan, Dr. Lynette (2001). Fresh Culinary Herb Production: a technical guide to the hydroponic and organic production of commercial fresh gourmet herb crops. New Zealand: Suntec. p. 15. ISBN 0473081075.

- Shores, Sandie (1999). Growing and Selling Fresh-cut Herbs. Pownal:VT: Storey Books. p. 78. ISBN 1580171281.

- Cranshaw, W.S. "Beneficial Insects and Other Arthropods, No. 550". Colorado State University Extension. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Parker-Clark, Vickie; Arnold, Barbara; Barney, Danny. "Small Farm Herb Production, is it for you?" (PDF). University of Idaho College of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-09.

- Shores, Sandie (1999). Growing and selling fresh-cut herbs. Pownal, VT: Storey Books. p. 2. ISBN 1580171281.