Henryk Dobrzański

Major Henryk Dobrzański (22 June 1897 – 30 April 1940) was a Polish soldier, sportsman and partisan. He was one of the first guerrilla commanders of the Second World War in Europe.

Henryk Dobrzański | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Hubal |

| Born | 22 June 1897 Jasło, Austria-Hungary (now in Poland) |

| Died | 30 April 1940 (aged 42) Near Opoczno, Poland |

| Years of service | 1912–1940 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | World War I, Polish-Ukrainian, Polish-Bolshevik, World War II |

| Awards | Krzyż Walecznych (4) Virtuti Militari (2) |

| Part of a series on the |

Underground State |

|---|

|

|

Authorities

|

|

Political organizations Major parties Minor parties

Opposition

|

|

Military organizations Home Army (AK) Mostly integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army Partially integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army

Non-integrated but recognizing authority of Armed Resistance and Home Army Opposition |

|

Related topics |

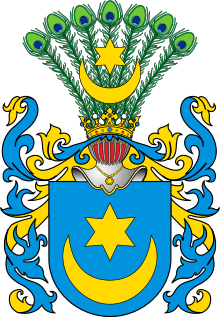

Early life and career

Henryk Dobrzański was born on 22 June 1897 in Jasło, Austria-Hungary to a Polish noble family (Coat of arms of Leliwa), of Henryk Dobrzański de Hubal and Maria Dobrzańska née Lubieniecka. In 1912 he joined the "Drużyny Strzeleckie", a Polish pro-independence youth organisation. When World War I broke out he volunteered to join Józef Piłsudski's Polish Legions. He served with distinction in the 2nd Regiment of Uhlans and participated in many battles such as Stawczany and Battle of Rarańcza. In 1918 after Poland regained its independence he joined the Polish Army.

He took part in the Polish-Ukrainian War of 1918 and fought with his cavalry platoon during the Siege of Lwów. Later he participated in Polish-Bolshevik War of 1919-1921. For his bravery he was awarded the Virtuti Militari, the highest Polish military award, and four times the Krzyż Walecznych, in addition to many other military awards.

After the Peace of Riga he remained in the Polish Army. He became a member of the Polish equestrian team, winning many international competitions. He also took part in the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam and came fourth at the prestigious Aldershot competition. In his sports career he gained 22 gold, three silver and four bronze medals altogether.

World War II

Shortly before the 1939 Invasion of Poland he was assigned to the 110th reserve Cavalry Regiment as a deputy commander. His unit was to enter combat as a second-line formation, but fast advances of the Wehrmacht made the completion of training impossible. On 11 September it was moved to Wołkowysk, from where it marched towards Grodno and Augustów Forest. It fought several skirmishes against the German army and took part in the defense of the city against the Red Army.

After two days of heavy fighting against the numerically superior Soviets, on 20 September Grodno was lost and three days later gen. bryg. Wacław Przeździecki, the commander of the defense of the Grodno area, ordered all his troops to escape to neutral Lithuania. The 110th Regiment was the only unit to disobey this order. The unit joined with the remnants of several routed regiments and fought its way towards the capital Warsaw. The unit got surrounded by the Red Army in the Biebrza river area and suffered serious casualties, but managed to break through the enemy defenses. After that, Lieutenant Colonel Jerzy Dąbrowski, the commander of the regiment, decided his unit should disband. A group of approximately 180 men wanted to continue, and Dobrzański took command of them and led them towards Warsaw, which was under siege.

Warsaw capitulated on 27 September, before Dobrzański and his men were able to reach it. That left him faced with three choices: disband, evacuate (via Hungary or Romania) to France, or continue the fight. Approximately 50 men volunteered to continue the fight. He led his unit southwards to try to break out and reach France. On 1 October 1939 they crossed the Vistula near Dęblin and started their march towards the Holy Cross Mountains. The same day his unit fought their first skirmish against the Germans. After that he decided to stay in the Kielce area with his unit and wait until the Allied relief came, which he expected in the Spring of 1940. He also swore that he would not take off his uniform until after the war. He named his force the "Separated Unit of the Polish Army" (Oddział Wydzielony Wojska Polskiego). On 6 October the Battle of Kock ended the resistance of the last major unit of the Polish Army. With the support of the local civilian population, Hubal and his men managed to evade the Germans.[1]

In March 1940 his unit inflicted heavy casualties on a number of German units in ambushes. The German authorities responded with reprisals against the civil population, burning several villages and killing an estimated 700 civilians. Due to these reprisals local sentiment turned against Hubal's unit, and the newly formed ZWZ became concerned that this would inhibit their ability to recruit. The ZWZ and the Government Delegate's Office at Home ordered Hubal to disband his unit. He refused to do so.[1]

Death and legacy

On 30 April 1940 his staff quarters, in a ravine near the village of Anielin (powiat of Opoczno), were ambushed. In an unequal battle Dobrzański and most of his men were killed. The Germans desecrated his body and put it on public view in the local villages. They then transported it to Tomaszów Mazowiecki and either burnt it or buried it in an unknown location. The remnants of the "Separated Unit of the Polish Army" continued the struggle until 25 June 1940, when it was disbanded.

In 1949 Dobrzański's son, Ludwik, emigrated to England and became a property developer. He died on 15 December 1990 in Bedford.

In 1966 Henryk Dobrzański was posthumously awarded the Golden Cross of the Virtuti Militari and promoted to Colonel. Currently almost 200 organisations and institutions bear his name, including 82 Scouting groups, 31 schools and several military units. There are streets named after him in almost every Polish city. The site of his burial remains unknown.

In 1973 the film Hubal, based on his resistance campaign, was released.

The pseudonym "Hubal" comes from his family coat of arms.

Hubal

Hubal Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1939

Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1939 Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1939

Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1939 Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1940

Hubal and his partisan unit, winter 1940 German soldiers with Hubal's body, 30 April 1940

German soldiers with Hubal's body, 30 April 1940- Memorial to Henryk Dobrzański in Kielce's old cemetery

Leliwa coat of arms

Leliwa coat of arms

Decorations

Military decorations awarded to Henyrk Dobrzański include:

- Order Virtuti Militari Golden Cross (posthumously in 1966)

- Order Virtuti Militari Silver Cross

- Cross of Independence

- Cross of Valour 4 times

- Medal Decade of regained Independence

- Commemorative Medal for War of 1918-1921

See also

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Polish Secret State

- List of guerrillas

References

- Citations

- Mazower 2008, p. Chapter 15.

- Bibliography

- Mazower, Mark Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe London, England, Penguine Books (2008).

Further reading

- Melchior Wankowicz: Hubalczycy, Warsaw, 1970;

- Marek Szymanski: Oddzial majora Hubala, Warszawa 1999, ISBN 83-912237-0-1;

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Z miejsca na miejsce. W cieniu legendy Hubala, Warsaw 1986, ISBN 83-904286-6-0;

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Kaja od Radoslawa, czyli historia Hubalowego krzyza, Warszawa 2006, ISBN 83-7319-975-6;

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Dwor w Krasnicy i Hubalowy Demon, Warszawa 2009, PIW, ISBN 978-83-06-03221-5;

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Lepszy dzien nie przyszedl juz, Warszawa 2012, Iskry, ISBN 978-83-244-0189-5;

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising, Introduction: Bruce E. Johansen. Lanham, MD and Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7391-7271-1.

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm: Polish Hero Roman Rodziewicz: Fate of a Hubal Soldier in Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Postwar England. Foreword by Matt DeLaMater. Lanham, MD and Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7391-7819-5.[1]

- Medical care in the unit of major Henryk Dobrzański aka "Hubal" D. Syryjczyk in Military Medicine and Pharmacy