Henry and Cato

Henry and Cato is a novel by Iris Murdoch. Published in 1976, it was her eighteenth novel.

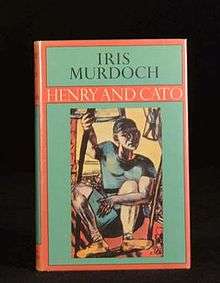

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Iris Murdoch |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Max Beckmann[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Chatto & Windus |

Publication date | 1976 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 340 |

| ISBN | 0701121955 |

| OCLC | 644376533 |

Set in London and the English countryside, the plot centres on two childhood friends who have not seen each other for several years. Henry is an art historian who returns to England from the United States upon inheriting his family estate, and Cato is a Roman Catholic priest who is losing his faith and has secretly fallen in love with a seventeen-year-old boy . Their stories, separate at the beginning of the novel, converge as it progresses.

The complex story is supported by formal plot symmetries and doubleness is an important theme throughout. The plot, which involves a violent kidnapping, has elements of the thriller genre. The book was generally favourably received by contemporary reviewers.

Plot

The two main characters, Henry Marshalson and Cato Forbes, were childhood friends who grew up as neighbours in the English countryside. As the novel begins, they are in their early thirties, and have not seen each other for several years. Their stories are presented separately at first but converge as the novel progresses.

Henry is the younger son of a wealthy landowner. On his father's early death, Henry's elder brother Sandy inherited all the property, including the family home, Laxlinden Hall. Henry went to the United States as a graduate student and then taught art history at a small midwestern college. When Sandy is killed in a car accident, Henry is his sole heir. Henry returns to Laxlinden, where his mother Gerda is living, to claim his inheritance.

Cato Forbes is a Roman Catholic priest living in a mission house in a poor area of London. Cato is the son of an atheist university professor and the older brother of Colette, who has left college and returned to her father's home. At the beginning of the novel the mission has been officially closed and the derelict house from which it operated has been condemned. Cato is in the process of losing his faith, and has secretly fallen in love with a seventeen-year-old boy called Beautiful Joe, who claims to be a petty criminal and an aspiring gangster.

Henry resolves to sell all his inherited property and give away the proceeds. Henry intends for his mother to live in a cottage in a nearby village, also part of the Marshalson estate. Her friend Lucius Lamb, a poet who has been living at Laxlinden Hall for several years, and whom Henry dislikes, will have to find a new home on his own. Henry first confides his plans to Cato, whom he visits in the mission, and Cato tries unsuccessfully to dissuade him. Their conversation is overheard by Joe, who questions Cato about Henry's wealth.

When going through his late brother's possessions, Henry discovers that Sandy had a flat in London. He visits the flat and finds a woman named Stephanie Whitehouse living there. Stephanie tells Henry that she was Sandy's mistress, and that she is a former sex worker, both stripping and full service. Henry begins an affair with her, and decides to marry her and take her back to the United States with him. When he tells his mother that he plans to sell the property and marry Stephanie, she at first protests but later seems to accept the situation. Henry takes Stephanie to stay at Laxlinden Hall, where she is befriended by Lucius and Gerda. Stephanie disagrees with Henry's plan to sell everything and leave the country, telling him she would like to live at Laxlinden. Gerda tries to promote a marriage between Henry and Cato's younger sister Colette, who has been in love with Henry since she was a child. Colette writes to him, declaring her love and proposing marriage, but he professes not to take her seriously.

Against the advice of his friend and fellow priest, Brendan Craddock, Cato decides to leave the priesthood and go away with Joe. He obtains a job teaching at a school in Leeds, and plans to support Joe while he gets an education. Cato asks Henry to lend him £500 to help him get started in his new life, and Henry sends him the money. However, Joe turns against Cato, refusing to go with him and telling Cato that he wants nothing to do with him now that he has left the priesthood. "I cared for you once, Father, but I cared for the other you, the one that wore a robe and had nothing, not even an electric kettle." [2]:211 In despair, Cato returns to Pennwood, his father's house. His father is delighted that he has lost his faith and intends to become a schoolmaster.

After a few days Cato goes back to the mission house in London, hoping that Joe will return. Joe does return, but kidnaps Cato and holds him for ransom in an abandoned air raid shelter, telling Cato that he working for a dangerous gang of criminals. He forces Cato to write a letter asking Henry for £100,000. Henry delivers part of the amount, and Joe demands that he bring the rest, after wounding him on the hand with a knife. Later, Joe gets Cato to summon his sister Colette, and when she arrives he tries to rape her, cutting her face with his knife when she resists. Hearing her cries, Cato manages to escape from an adjoining room where he has been locked up, and hits Joe on the head, killing him. Colette survives the attack, and she and Cato are rescued.

Back at Laxlinden Hall, Stephanie decides to return to London rather than marry Henry and go to the United States. Henry decides not to sell Laxlinden after all, but to live there and develop a model village on his property. At the end of the novel, Henry has married Colette, and Cato is on his way to Leeds to take up his teaching job.

Major themes

At the beginning of the novel each of the two main characters is at a turning point in his life. Their stories overlap and intertwine throughout, as the third-person narrative focusses alternately on Henry and Cato. The complex structure is supported by formal symmetries in the characters' situations. For example, Henry and Cato's parents are a widow and a widower respectively, Henry had an older brother and Cato has a younger sister, and Henry is sexually attracted to an older woman with whom he plans to share his life, while Cato is similarly attracted to a young boy.[3] Lorna Sage remarks in her review of the novel that this deployment of "multiple contrasts and operlaps of its two heroes' careers" is "a technique at which Miss Murdoch has become so carelessly expert that one soon loses sight of its crude binary origins".[4]

Henry and Cato is one of several Murdoch novels that borrows elements from the thriller genre. The opening scene describes Cato getting rid of a revolver, which we later find out belonged to Joe, by throwing it off a bridge into the Thames. Later, Cato is kidnapped and held prisoner, and there are several acts of criminal violence in the book.[5]

Visual art is an important theme in the novel.[4] Henry has been making a living teaching art history, and is supposed to be writing a book about Max Beckmann. Henry admires Beckmann's "vast self-confidence, that happy and commanding egoism".[2] :5 Beckmann's 1940 painting Acrobat on Trapeze was used for the cover of the first English edition of Henry and Cato. Part of Henry's inheritance is a seventeenth-century Flemish tapestry in the library at Laxlinden Hall. It depicts the goddess Athena seizing Achilles by the hair. The tapestry is taken down in preparation for being sold when Henry plans to get rid of his inheritance, and is replaced at the end after he changes his mind.[4]

Plato's Allegory of the Cave provides the novel's central metaphor for vision and moral change. According to Peter J. Conradi, Henry wants to renounce the world and live in the sun, while Cato, having lost his faith, is trying to return to the cave.[6] :279 Cato's sudden conversion is described in Platonic terms, as he feels "as if he had not only emerged from the cave, but was looking at the Sun and finding that it was easy to look at".[2]:29 Suguna Ramanathan, in her study of Murdoch's fiction, observes that this description points to a lack of authenticity in his conversion. In Plato's account, the Good, of which the sun is a symbol, is painful to look at unless one has prepared oneself by long and serious effort. "In this case, either it is not the sun, or Cato is looking at it through the protecting glass of his romantic nature".[7]:47

Literary significance and reception

Henry and Cato was Iris Murdoch's eighteenth novel, and several reviewers addressed possible objections arising from her prolific output and continuity of themes. The Washington Post review approvingly compared her "essentially 19th-century way of writing and working" to that of Anthony Trollope, and called Henry and Cato "another star for her literary firmament".[3] In The New York Times, Anatole Broyard countered the suggestion that Iris Murdoch "writes too many novels and they are all the same" by saying that "having mastered her particular form and style", Iris Murdoch should continue to work in the same vein as long as it suited her to do so.[8] Lorna Sage remarked that Murdoch's large and regular output demonstrated her "gift for making the variety of possible plots and characters seem inexhaustible".[4]

The critical response was generally favourable. Joyce Carol Oates called Henry and Cato "Murdoch's finest novel to date, and surely one of the major achievements in fiction in recent years". Because the characters and plot are convincing the ideas and themes are realistically "embodied in the narrative", which is not always the case in Murdoch's novels, according to Oates.[9] Broyard found that "just about every major character ... comes off as successful", while Sage takes particular note of the minor character Lucius Lamb as a "horribly sympathetic and funny creation".[4][8] The Times review singled out the strong female characters for mention. Supposedly secondary characters, Gerda, Stephanie and Colette "imprint their will on the two men".[10]

Less positive contemporary reviews also remarked on the characters. Writing in The Globe and Mail, Margaret Laurence acknowledged the "narrative skill" and "intelligence" displayed in Henry and Cato, but found the characters unrealistic and too often merely representatives of the author's views.[11] William H. Pritchard in The New York Times found the plot entertaining but unconvincing and "less psychologically interesting than one could wish". On the other hand, he called her descriptive passages "truly entertaining and permanently valuable" and the book as a whole "an engaging and striking work".[12]

Peter Conradi describes Henry and Cato as an "extraordinary, accomplished mixture of farcical comedy and melodrama".[6]:279 His discussion of the novel takes doubleness to be the main theme, and more specifically "chiasmus", in that the stories of the two men increasingly intersect and mirror each other. In her study of Murdoch's work, Hilda Spear includes Henry and Cato as the last of a group of four novels, beginning with The Black Prince, in a chapter called Metaphors for Life. The chapter title points to the fact that each of the novels is written in a "consciously deliberate" narrative style, in which the reader is reminded that "a story is being told". In this novel, this is accomplished by the third-person double narrative and the chiasmus noted by Conradi, in which "the overtly good" (i.e. Cato the priest) "moves toward evil and the apparently bad" (i.e. Henry the iconoclast) "strives towards good". This narrative style does not prevent the reader from becoming absorbed in the plot, however, and Spear suggests that Henry and Cato is among Murdoch's most accessible novels.[5]:74–75

In Iris Murdoch: Figures of Good, Suguna Ramanathan maintains that goodness is "the central preoccupation of the later novels". Brendan Craddock, Cato's friend and fellow priest, is a seemingly minor character who represents "a clearly defined good figure".[7]:1–2 Some critics have suggested that Murdoch relied too much on such characters as spokesmen for her own ideas.[9] On the contrary, Ramanathan argues that Brendan's character is the "deep structure on which the novel rests".[7]:1 His role is not just to give spiritual counsel and advice which Cato is unable to take, but by his own behaviour as a priest to provide a contrast with the ego-driven actions of Cato.[7]:43

References

- Saint Louis Art Museum. "Acrobat on Trapeze, 1940". Highlights of the Collection.

- Murdoch, Iris (1977). Henry and Cato. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0670366978.

- Weeks, Brigitte (9 January 1977). "Weaving the tapestry of the prodigal sons". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. 137.

- Sage, Lorna (1977). "The pursuit of imperfection". Critical Quarterly. 19 (2): 61–68. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8705.1977.tb01613.x.

- Spear, Hilda D. (2007). Iris Murdoch (2 ed.). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403987099.

- Conradi, Peter J. (2001). The Saint and the Artist: a Study of the Fiction of Iris Murdoch (3rd ed.). London: Harper Collins. ISBN 9780007120192.

- Ramanathan, Suguna (1990). Iris Murdoch: figures of good. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312045042.

- Broyard, Anatole (7 January 1977). "Books of The Times". New York Times. New York, N.Y. p. 56.

I don't see how we can have too many novels of people in significant and universally appealing crises finding themselves forced to make a philosophic leap of some sort that will illuminate their whole lives.

- Oates, Joyce Carol (18 December 1978). "Sacred and profane Iris Murdoch". New Republic. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Gillott, Jacky. "Fiction". The Times. London, England. p. 11.

- Laurence, Margaret (2 December 1976). "On Murdoch's sexual merry-go-round". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada.

- Pritchard, William H. (16 January 1977). "Murdoch's eighteenth: Henry And Cato". New York Times. New York, N.Y. Retrieved 20 January 2015.