Henry Koerner

Henry Koerner (born Heinrich Sieghart Körner; August 28, 1915 – July 4, 1991) was an Austrian-born American painter and graphic designer best known for his early Magical Realist works of the late 1940s and his portrait covers for Time magazine.

Henry Koerner | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 28, 1915 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 4 July 1991 (aged 75) St. Pölten, Austria |

| Spouse(s) | Joan Marlene Frasher (February 29, 1932 - September 12, 2013) |

| Children | Joseph Leo Koerner (born June 17, 1958) Stephanie Beth Koerner (born July 22, 1954) |

Early life

Born in the Leopoldstadt District of Vienna to non-observant Jewish parents Leo Körner (1879–1942) and Feige ("Fanny") Dwora Körner née Mager (1887–1942), Koerner attended the Realgymnasium Vereinsgasse. Trained in graphic design at Vienna's Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (1934–36), he worked in the studio of Viktor Theodor Slama, designing posters and book jackets. Following Hitler's annexation of Austria in 1938, he fled via Italy (Milan and Venice) to the United States, settling in New York and in 1940 marrying Viennese-born Fritzi Apfel.[1]

Employed as a commercial artist in Maxwell Bauer Studios in Manhattan, he achieved initial success as a poster artist, receiving first prize from the American Society of the Control of Cancer Poster Competition and two first prizes from the National War Poster Competition. In 1943, the Office of War Information hired Koerner in its Graphics Division in New York, where he worked alongside artists Ben Shahn, Bernard Perlin, and David Stone Martin. Shahn's pictorial style, along with the photography of Walker Evans and German Neue Sachlichkeit painters (e.g., Otto Dix), inspired Koerner's painting, which began with a rendering of his family home in Vienna (My Parents I, 1944). That first painting is the subject of the film "The Burning Child" [2]

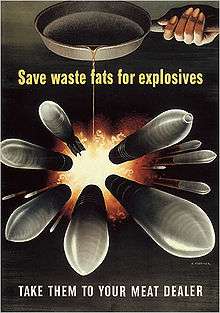

Drafted into the U.S. Army, he was ordered in 1944 to the Graphics Division of the Office of Strategic Services in Washington, D.C. where he made war posters, including Save Waste Fats and Someone Talked, the latter winning an award from the Museum of Modern Art. Shipped to London, he documented, in pen and ink sketches and photographs, everyday life during wartime. After VE Day (8 May 1945), Koerner was reassigned to Germany, working in Wiesbaden and Berlin, and sketching defendants at the Nuremberg trials.

Magical realism

Discharged from the army in 1946, Koerner returned to Vienna to discover that his parents and brother (Kurt, b. 1913), as well as all but two of his relatives, had been deported and killed. Photographs taken by the artist on this trip were discovered posthumously and exhibited in exhibitions in Naples, Florida and Columbus, Ohio.

In Berlin, having joined the Graphics Division of the U.S. Military Government, he painted his first major works, including My Parents II (Curtis Galleries, Inc., Minneapolis), The Skin of Our Teeth (Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska), and Vanity Fair (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). These paintings were exhibited in 1947, to international acclaim, in a one-person show at Berlin's Haus am Waldsee—the first exhibition of American modern art in post-war Germany and the first and for many years the only art exhibition in Germany to reflect on the holocaust. [3] Although Auschwitz had been liberated less than two years earlier, and while a generation later artists would base their undertaking on the exploration of problems of historical trauma, memory, and amnesia, some American critics complained of what they perceived as Koerner's unwarranted "bitterness" and "hysterical I-told-you-so path," advising him and like-minded artists to look forward, not back. [4]

Returning to New York later that year, Koerner exhibited the Berlin works in an exhibition at Midtown Galleries, which represented him until 1964. Life magazine wrote of the show: "No new artist in years has been accorded the sudden, unanimous praise received by Koerner."[5] Critics associated his work that of other so-called Magic, (or Symbolic) Realists such as Paul Cadmus and George Tooker.[6][7]

Inspired by the structural logic of Giotto's frescoes in the Arena Chapel, Koerner created in 1948–49 a new series of paintings—all in the same scale and viewpoint and focused on the American scene—that absorbed fantastical elements into the fabric of everyday life.

Pittsburgh

From 1952 to 1953, Koerner was Artist-in-Residence at Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University) in Pittsburgh, PA, where he met his second wife, Joan Marlene Frasher (born 1932, Escanaba, Michigan), a violinist and undergraduate music major at the College. He settled in Pittsburgh's Squirrel Hill neighborhood, which through its geography of hills and bridges, and its long-established Jewish community, reminded him of Vienna. He used friends, family, and students as models. Although a well-known personality in Pittsburgh, Koerner's pictures—enigmatic, comical, and often monumental in scale—baffled many art critics.[8]

From 1955 to 1967, Koerner painted over fifty portrait covers for Time magazine. Because he refused to work from photographs, all Koerner's sitters, including Maria Callas, John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Paul Getty, Jimmy Clark, and Barbra Streisand, posed for many hours for their portraits, usually during the most eventful times of their lives; but this method gave their likenesses an immediacy meant to outdo photographs, which were increasingly featured on Time's covers as it confronted an ever more competitive market. From 1966 on, annual trips to Vienna shifted Koerner art from American subjects, which occupied him previously, to ones mingling the landscapes and people of Vienna and Pittsburgh. The center of Koerner's output were large-scale allegorical paintings made up of sixteen canvases assembled in four rows of four.[9] In 1965 he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became a full Academician in 1967.

Late style and death

Koerner produced many thousands of works in his career. In the 1980s, he worked mostly in watercolor, pressing the medium to monumental tasks and formats, including three monumental 16-panel paintings executed on heavy watercolor paper stretched like canvas over wooden frames.

During the last decade of his life, Koerner painted again mainly in oils, favoring a new, square format, and simplifying his motifs. In these works "Koerner condense[d] his experience as a plein-air painter of uncanny views."[10] Increasing interest in émigré artists brought his work new critical notice in Austria and the States.[11] After his death, his work was shown in a major retrospective in Vienna (1997) and an exhibition of his early work at the Frick Art and Historical Center in Pittsburgh (2003). Koerner's first painting, My Parents I, features prominently in Joseph Koerner's 2019 film The Burning Child.

Koerner died in 1991 in St. Pölten, Austria, following complications from a hit-and-run accident on his bicycle in the Wachau in Austria. He is buried beside his wife in Pittsburgh's Homewood[12] Cemetery. His son Joseph Koerner is a professor of history of art at Harvard University and a documentary film-maker. His daughter Stephanie Koerner is a lecturer at Liverpool University's School of Architecture.

Solo exhibitions (selection)

- Ausstellung Henry Koerner U.S.A. Gemälde und Graphik. Haus am Waldsee, Berlin. 1947.

- Henry Koerner. Midtown Galleries, New York, NY. 1948.

- Retrospective Exhibition of the Work of Henry Koerner. Pennsylvania College for Women, Pittsburgh, PA. 1952.

- Henry Koerner. Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings. M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, CA. 1953.

- Henry Koerner. Hammer Galleries, New York, NY. 1964.

- Henry Koerner Retrospective Exhibition. Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, PA. 1971.

- Henry Koerner. Concept Art Gallery, New York, Ny. 1981.

- Henry Koerner, From Vienna to Pittsburgh: The Art of Henry Koerner. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA. 1983.

- Unheimliche Heimat—Henry Koerner 1915–1991. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna. 1997.

- The Early Work of Henry Koerner. The Frick Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. 2003.

- Henry Koerner's Pittsburgh. Chatham University, Pittsburgh, PA. 2009.

- Henry Koerner: The Real and Imagined. The Von Liebig Art Center, Naples, FL. 2010–2011.

- Real Portraits: Time Covers by Henry Koerner. Yale University. 2015.

Bibliography

- Haus am Waldsee, Ausstellung Henry Koerner: Gemälde und Graphik, 1945–1947. Berlin, Haus am Waldsee, 1947.

- Cora Sol Goldstein, Capturing the German Eye: American Visual Propaganda in Occupied Germany. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 91–96.

- Gail Stravitzky, From Vienna To Pittsburgh: The Art of Henry Koerner, exh. cat. Pittsburgh: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, 1983.

- Emigrants and Exiles: A Lost Generation of Austrian Artists in America, 19200-1950. Exhibition Catalogue by John Czaplicka and David Mickenberg. Evanstan: Mary and Leigh Block Gallery, Northwestern University, 1996.

- Cozzolino, Robert. "Henry Koerner, Honoré Sharrer, and the Subversion of Veauty: 'Magic Realism' and the Photograph." In Shared Intelligence: American Painting and the Photograph, pp. 102–121. Exhibition catalogue ed. Barbara Buhler Lynes and Jonathan Weinberg. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011.

- Joseph Leo Koerner, Unheimliche Heimat—Henry Koerner 1915–1991, exh. cat. Vienna: Österreichische Galerie, 1997.

- The Early Work of Henry Koerner. Exh. cat. by Edith Balas. Pittsburgh: Frick Art & Historical Center, 2003.

- Real Portraits: "Time" Covers by Henry Koerner. Exh. cat. by Annabel Patterson, Philip Eliasoph and Jonathan Weinberg. New Haven: Yale University, 2015.

- Artists in Exile: Expressions of Loss and Hope. Exh. cat. ed. by Franke V. Josenhans. New Haven: Yale University, 2015, pp. 31–47.

- Kathrin Hoffmann-Curtius, with Sigrid Philipps, Judenmord: Art and the Holocaust in Post-war Germany, trans. Anthony Mathews. London: Reaktion Books, 2018.

References

- Gail Stravitzky, From Vienna To Pittsburgh: The Art of Henry Koerner, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, 1983), pp. 13–17.

- IMDb

- Kathrin Hoffmann-Curtius, Judenmord: Art and the Holocaust in Post-war Germany (London, 2018), pp. 150-154.

- Haus am Waldsee, Ausstellung Henry Koerner: Gemälde und Graphik, 1945–1947 (Berlin, 1947); Cora Sol Goldstein, Capturing the German Eye: American Visual Propaganda in Occupied Germany (Chicago 2009), pp. 91–96.

- Life, May 10, 1948.

- Symbolic Realism in American Painting 1940–1950, exh. cat. (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1950), p. 8.

- Cf. Roberto Cozzolino, "Henry Koerner, Honoré Sharrer, and the Subversion of Veauty: 'Magic Realism' and the Photograph." In Shared Intelligence: American Painting and the Photograph, pp. 102–121.

- Stravitzky, pp. 19-20.

- Joseph Leo Koerner, Unheimliche Heimat—Henry Koerner 1915–1991, exh. cat. (Vienna: Österreichische Galerie, 1997), pp. 57–75.

- Unheimliche Heimat, p. 71.

- E.g., Czaplicka and Mickenberg.

- newspapers.com