Hennessy & Hennessy

Hennessy & Hennessy was an architectural firm established in 1912 in Sydney, Australia that was responsible for a series of distinctive Art Deco office buildings in the 1930s in all capital cities in Australia, as well as New Zealand and South Africa, designed by John (Jack) Hennessy (1887–1955), described as Australia's first international architect.[1] The firm was also responsible for many projects for the Catholic Church in Brisbane in the 1920s, including the never-built Holy Name Cathedral, Brisbane, which would have been 'the largest sacred building in the Commonwealth', as well as the Great Court of the University of Queensland.

John Francis Hennessy, father and son

The firm's name dates from the period when John Francis Hennessy took his son, also named John Francis (Jack) Hennessy, but often known as Jack Hennessy, into his architectural firm as a partner in 1912.

The first John Francis Hennessy (1853–1924) was born in Ireland about 1853, and grew up and trained in architecture in Leeds, and London.[2] Deciding that there were more opportunities in Australia, he arrived in Sydney in 1880 and was soon appointed assistant to the City of Sydney architect, where he designed Centennial Hall of the Sydney Town Hall in 1883,[2] (working on it after he left that position).

Jack Hennessy then went into private partnership with Joseph Ignatius Sheerin as Sheerin & Hennessy from 1884, and they went on to design a number of projects for the Catholic Church in Sydney, and the Cathedral in Armidale. Commercial designs included Hordern Bros' drapery store (1886), the Tattersall's Club (1892) in Pitt Street, and ten stores for (Sir) John See., and they also designed many large suburban residences were built to their plans.

Sheerin left the partnership in 1912, and Hennessy then went into partnership with his son, also named John Francis Hennessy, who was also known as Jack Hennessy, and the firm became Hennessy & Hennessy. Born in 1887, Jack Hennessy had studied architecture at Sydney Technical College and at the University of Pennsylvania, returning to Australia in 1911, joining his father's firm the next year.[1] John Hennessy retired in 1923, and died on November 1924 and was buried in Rookwood Cemetery.[3] Jack Hennessy became principal of the firm, retaining the name (though they were also known as Hennessy, Hennessy & Co.). In 1925-6 the firm had more partners and was briefly known as Hennessy & Hennessy, Keesing and Co and J.P. Donoghue, but after 1926 reverted to Hennessy, Hennessy & Co / Hennessy & Hennessy.

Architectural practice

The year the younger Hennessy joined the firm they gained one of their most prestigious commissions, the completion of the huge Gothic Revival St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney. Designed by William Wardell, only the apse, crossing and transept had been finished; the Hennessy's were to build the nave and south front to Wardell's design, as well as the crypt, built to their design. Further commissions for the Catholic Church followed with St Patrick's Hall in Sydney in 1915.

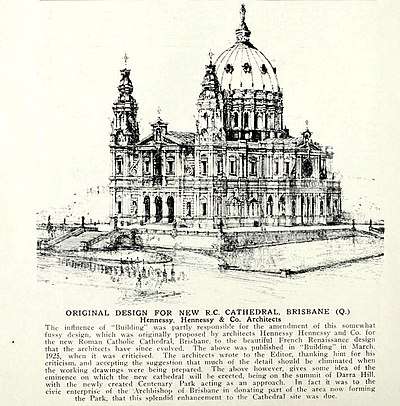

Bishop James Duhig, having already become friends with the younger Hennessy, became a major patron once he was elevated to Archbishop of Brisbane in 1917. Beginning with the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Toowong, completed in 1920, Hennessy and Hennessy designed the Convent of the Sacred Heart (1922), St Vincent's Hospital (1922) and the Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola(1929) all in Toowong, Corpus Christi Church in Nundah (1926) and the Villa Maria Convent, in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane (1928). They were also commissioned to complete the 19th century Brisbane Catholic Cathedral St Stephen's in 1920-22, in a smaller form than original envisaged because he had plans to build a far grander cathedral on another site. In 1925 Jack Hennessy produced a plan for a huge church intended to be "the largest sacred building in the Commonwealth" for a site in Fortitude Valley on the edge of the central city. The Renaissance/Baroque style design, inspired by St Paul's in London, had a dome and paired front towers, and was to be called the Holy Name Cathedral Construction began in 1927, but by the early 1930s only some retaining walls and the crypt had been built, and no further work was ever undertaken.

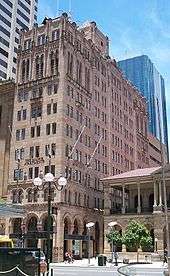

In the 1930s Hennessy designed a series large office buildings for three different insurance firms in three countries, and has been described as Australia's first international architect.[1] The series of buildings for the Colonial Mutual Life insurance company were all versions of each other, in different sizes, in an elaborate Romanesque/Norman style, complete with gargoyles.

Another major project was the Great Court, University of Queensland in St Lucia, Brisbane, built between 1938-1979.[1]

In 1950, Hennessy was awarded over £25,000 by the court when he sued to recover his unpaid fees for the Holy Name Cathedral.[4]

Hennessy died of heart disease at his eldest son's home in Sydney on September 4, 1955, at the age of 68. He was buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery at Rookwood. The firm continued until 1968.[1]

Major works

- 912-1940s: completion of St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney

- 1915: St Patrick's Parish Hall and Girls' School, Harrington Street, Sydney[1]

- 1920: Stuartholme (Convent of the Sacred Heart), Toowong, Brisbane.[1]

- 1922: Cathedral of St Stephen, Brisbane, apse and transepts

- 1922: St Vincent's Hospital, Toowoomba[1]

- 1925-31: Christian Brothers' Training College (Mount St Mary) Strathfield, Sydney.[1]

- 1926: Corpus Christi Church in Nundah, Brisbane[5]

- 1927-28: Villa Maria Convent, Fortitude Valley, Brisbane[6]

- 1929: Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola in Toowong, Brisbane[7]

- 1930-31: Colonial Mutual Life, Brisbane[8]

- 1931-33: Colonial Mutual Life, Durban, South Africa[9]

- 1934: Colonial Mutual Life, Adelaide[10]

- 1935: Colonial Mutual Life, Wellington, New Zealand (demolished)[11]

- 1934: Prudential Insurance, Wellington, New Zealand[12]

- 1934-5: Cardinal Cerretti Memorial Chapel, St Patrick's Seminary, Manly, Sydney.[13]

- 1935: Colonial Mutual Life, Port Elizabeth, South Africa[1]

- 1936: Lawson Apartments, Perth

- 1936: Colonial Mutual Life, Perth (demolished)[14]

- 1936: Australasian Catholic Assurance, Sydney[1]

- 1936: Australasian Catholic Assurance, Melbourne[1]

- 1937: Colonial Mutual Life, Hobart[1]

- 1937: Colonial Mutual Life, Newcastle[1][15]

- 1937 Challis House, Martin Place, Sydney[16]

- 1937: St John of God Hospital, Belmont (Rivervale), Perth (demolished)[1]

- 1937-79: Great Court, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane[17]

- 1939: Colonial Mutual Life, Great Charles Street, Birmingham, UK[18]

- 1939: Prudential Insurance, Martin Place, Sydney (demolished)[19]

- 1941: Pius XII Provincial Seminary, Banyo, Brisbane.

Gallery

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane design 1925

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane design 1925.jpg) Villa Maria Hostel, 1928

Villa Maria Hostel, 1928- St Ignatius Church, Toowong, 1929

Colonial Mutual Life, Brisbane, 1931

Colonial Mutual Life, Brisbane, 1931 Colonial Mutual Life, Brisbane, 1931

Colonial Mutual Life, Brisbane, 1931 Colonial Mutual, Durban, South Africa, 1933

Colonial Mutual, Durban, South Africa, 1933 Colonial Mutual Life, Adelaide, 1934

Colonial Mutual Life, Adelaide, 1934 Colonial Mutual Life, Hobart, 1937

Colonial Mutual Life, Hobart, 1937 Australian Catholic Assurance Building, Melbourne, 1936

Australian Catholic Assurance Building, Melbourne, 1936- Prudential Insurance, Wellington, New Zealand, 1835

Prudential Insurance Martin Place, Sydney, 1939

Prudential Insurance Martin Place, Sydney, 1939_02.jpg) Lawson Apartments, Perth, 1937

Lawson Apartments, Perth, 1937 Queensland University Great Court frontage in 1948

Queensland University Great Court frontage in 1948 The Great Court, University of Queensland

The Great Court, University of Queensland

References

- East, John W (2013). Australia's first international architect: a sketch of the life and career of Jack F. Hennessy junior (PDF). St Lucia QLD, Australia. pp. 1–79. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Howard, Rod. "Hennessy, John Francis (Jack) (1853–1924)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "DEATH OF J. F. HENNESSY". The Catholic Press (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1942). Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 6 November 1924. p. 25. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "£25,720 TO HENNESSY". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 17 May 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Corpus Christi Church (entry 601460)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- East, John W (2013). Australia's first international architect: a sketch of the life and career of Jack F. Hennessy junior (PDF). St Lucia QLD, Australia. pp. 1–79. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola (entry 602532)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Newspaper House (entry 600150)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Colonial Mutual Building, Durban | 103515 | EMPORIS". www.emporis.com. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Australia, 5000 Adelaide. "CML Building | Adelaidia". adelaidia.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- specified, Not (1 January 1935). "Colonial Mutual Life building, Wellington". Colonial Mutual Life building, Wellin... | Items | National Library of New Zealand | National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Prudential Assurance Building - Wellington Heritage - Absolutely Positively Wellington City Council Me Heke Ki Poneke". wellingtoncityheritage.org.nz. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Cardinal Cerretti Memorial Chapel". dictionaryofsydney.org. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "The beauty Perth lost in the name of progress". The West Australian. 21 May 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Colonial Mutual Life Building | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Commercial Building "Challis House" Including Interior | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- East, John (August 2014). "Jack F Hennessy, Architect of the Great Court at The University of Queensland" (PDF). Fryer Folios. 9 (1): 15–19. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "CML Building, Great Charles Street, Birmingham". manchesterhistory.net. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Sydney Architecture Images- Prudential Building". sydneyarchitecture.com. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

External links

- "Hennessy & Hennessy". Artefacts.