Holy Name Cathedral, Brisbane

Holy Name Cathedral was a planned but never-built Roman Catholic cathedral for the city of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Designed by Hennessy, Hennessy & Co, initially in an English Baroque style inspired by St Paul's in London, it was intended to have been the largest church building of any Christian denomination in the Southern Hemisphere. James Duhig, the Archbishop of Brisbane, was the chief proponent of the project. First designed in 1925, building began in 1927 and in the 1930s services were held in the crypt chapel on the site, the only part to be built. No further construction took place, and with Duhig's death in 1965 the project lost its impetus, but was not formally abandoned until the 1970s. The archdiocese sold the site to property developers in 1985, the crypt was demolished and an apartment complex was built on the site. Today the perimeter wall along Ann Street and part of Gotha Street are all that remain, and were heritage-listed in 1992.

Duhig the Builder

In the early years of Duhig's ecclesiastical provinciate, his archdiocese took on an extensive building program, including churches, hospitals and schools, creating his nickname "Duhig the Builder".[1] Projects included the Convent of the Sacred Heart, St Vincent's Hospital, Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola in Toowong 1920s,[2] and the Corpus Christi Church in Nundah in 1926.[3] Within Brisbane, he commissioned the Villa Maria Convent in Fortitude Valley, built in 1927-28. With plans to build a new, larger Cathedral, he completed the existing 19th century Cathedral of St Stephen, Brisbane, with an apse and sanctuary in a simpler design than originally intended in 1922.

Site

The site chosen for the cathedral was in part that of the Bishop's residence, located on a rise just outside the central city, at the southwestern end of the inner suburb of Fortitude Valley, bounded by Gotha and Gipps, Ann and Wickham Streets (27.4596°S 153.0327°E).

A house called "Dara" had been built on that site in 1850, and in 1859 it became the residence of the first Catholic Bishop of Brisbane, James Quinn (1859–1881).[4] In 1890 the house was replaced by a more substantial dwelling of the same name for the second bishop, Robert Dunne (1830–1917). It was then occupied by his successor Archbishop Duhig from 1917 until he demolished it to make way for his Holy Name Cathedral project.[4]

The rear part of the site on Gipps Street, where the crypt of the Cathedral was eventually built, was owned by Simon Kreutzer (1865-1926), who sold it for a nominal rate to the Brisbane Town Council as a possible site for a new town hall.[5] However, Charles Moffatt Jenkinson, the mayor of Brisbane in 1914, decided to construct the Brisbane City Hall at Albert Square (now known as King George Square), and he committed the council to that decision by selling the Fortitude Valley site to the Catholic Archdiocese for the construction of the cathedral.[6][7]

Design

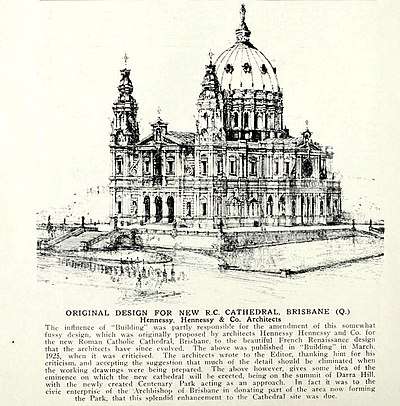

Holy Name Cathedral was designed by the Sydney-based firm of architects Hennessy, Hennessy & Co.[4]

It was intended to be "the largest sacred building in the Commonwealth", being 330 feet (100 m) long, 220 feet (67 m) wide and 270 feet (82 m) high. It was to be capable of seating 4,000 people.[8] This would have in fact been slightly smaller than Saint Joseph's Oratory in Montreal, Canada, which is 344 by 213 feet (105 by 65 m), which had just begun construction in 1924. St Joseph's was a modified version of the original design of 1914, which bears strong similarities with the Holy Name Cathedral.

A report, with published plans, in Building magazine of 12 September 1927, shows the perspective sketch at the top of this article, which is stated as the first design from 1925, and was 'somewhat fussier' than the final design shown in the plans of 1927.

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane design as published 1927:

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane elevation

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane elevation Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane section

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane section Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane plan

Holy Name Cathedral Brisbane plan

Benedict stone

Benedict stone is a mixture of cement and crushed Brisbane tuff used on building facades as an alternative to full stone construction. It was manufactured by Benedict Stone (Qld) Pty Ltd which was established by Roman Catholic Archbishop of Brisbane James Duhig, to manufacture the stone required for the Holy Name Cathedral, Fortitude Valley. The product was developed at the turn of the twentieth century by American manufacturer, Benedict. Duhig obtained a licence from America and opened the Benedict Stone works at Bowen Hills on 9 August 1929. In February 1930 Colonial Mutual Life (CML) advanced Duhig a £70,000 mortgage on his properties which included the stone works. A mutually-dependent relationship developed between CML, Duhig and Jack Hennessey, architect. CML used Benedict stone to build a number of their Australian offices, ensuring some of their mortgage was repaid and employed Hennessey and Concrete Constructions (Qld) Ltd, Brisbane (Duhig's architect and contractor for the Holy Name Cathedral).[9]

Construction commences

Concrete foundations for the building were laid in 1927, and the foundation stone was laid on 14 Sept 1928 by the papal legate, Cardinal Cerretti, with a crowd of 35,000 people in attendance.[10] Due to the Great Depression which began in late 1929, fund-raising efforts in the 1930s stalled. Because of lack of funds caused by unwise investment in oil shares of the Roma oil wells the dream did not come to fruition.[11] Nevertheless, Duhig managed to raise enough funds to build a crypt on the site which was completed in 1934.[4] In August 1935, the principal altar in the crypt was consecrated by Duhig.[12] However, fundraising efforts stalled shortly thereafter.[13]

The Holy Name Cathedral project was subject to further ongoing setbacks. In 1949 the Holy Name architect Jack Hennessy sued for unpaid fees and in 1950 the court awarded him over £25,000.[1][14]

The cathedral was never completed. In 1985 the archdiocese sold the site to property developers and an apartment complex called "Cathedral Place" was subsequently built. The perimeter walls of the cathedral which were topped by balustrades on the boundaries along Ann Street and part of Gotha Street have been preserved. The surviving remnants of the cathedral were heritage-listed in 1992.[15] St Stephen's Cathedral in the central business district continues to be the seat of the Catholic Archbishop of Brisbane.

Cathedral Place courtyard

Cathedral Place courtyard Balcony overlooking the street

Balcony overlooking the street

References

- "Who was James Duhig?". www.uq.edu.au/ University of Queensland. 8 December 2006. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- East, John W (2013). Australia's first international architect: a sketch of the life and career of Jack F. Hennessy junior (PDF). St Lucia QLD, Australia. pp. 1–79. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Corpus Christi Church (entry 601460)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Holy Name Cathedral Site". www.epa.qld.gov.au/ Environmental Protection Agency (Queensland). 8 December 2006. Archived from the original on 16 January 2004. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- Simon Kreuezer "was famous as a blacksmith". A photo of Simon outside his shop in about 1906 is available. Simon was of 8 children born to Christian Kreutzer,(1824-1896) a vinedresser, and Marianne (née Moledar)(born 1827) from Kaferthal, Baden, Germany who had sailed in 1852-3 on the 'Johan Cosar' to Sydney and later farmed land on the banks of Kedron Brook and had a house where the 'Toombultown' shopping centre is now . They were literate Roman Catholics and had 30 grandchildren in Australia. Source : "They came from Pommern (Prussia)", 1982 and First Addendum, 1984.

- "Charles Jenkinson dies". Sunday Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 4 July 1954. p. 3. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "CITY IMPROVEMENTS". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 23 May 1914. p. 4. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "LARGEST IN AUSTRALIA". The Daily News. Perth: National Library of Australia. 14 July 1927. p. 2 Edition: HOME (FINAL) EDITION. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Newspaper House (entry 600150)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Holy Name Cathedral". The Longreach Leader. Qld.: National Library of Australia. 21 September 1928. p. 26. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "They came from Pommern (Prussia)." 1982 p 176.

- "HOLY NAME CATHEDRAL CRYPT". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 17 August 1935. p. 19. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Atfield, Cameron (19 April 2015). "Catholic cathedral exists in name only". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "£25,720 TO HENNESSY". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 17 May 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Holy Name Cathedral Site (entry 600208)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holy Name Cathedral, Brisbane. |

- "History of Cathedral Place". Archived from the original on 3 October 2008.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Laying of the foundation stone".