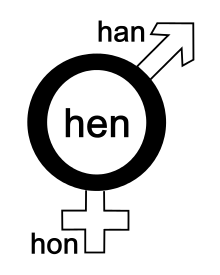

Hen (pronoun)

Hen (Swedish: [ˈhɛnː] (![]()

It is currently treated as a neologism by Swedish manuals of style. Major newspapers like Dagens Nyheter have recommended against its usage, though some journalists still use it. The Swedish Language Council has not issued any specific proscriptions against the use of hen, but recommends the inflected forms hens ("her(s)/his") as the possessive form and the object form hen ("her/him") over henom, which also occurs. Hen has two basic usages: as a way to avoid a stated preference to either gender; or as a way of referring to individuals who are agender, genderqueer or non-binary, or those who reject the notion of binary gender on ideological grounds.

Linguistic background

The Swedish language has a set of personal pronouns which is more or less identical in form to that of English. The common pronouns used for human beings are either han ("he") or hon ("she"). While Swedish and Danish historically had the same set of three grammatical genders as modern German, with masculine, feminine and neuter, the three-gender system fell out of use from the dialects out of which the respective standard languages were developing sometime in the late Middle Ages. The system contracted so that words of masculine and feminine gender folded into a common gender while the neuter gender remained. In Swedish and Danish, there are two words that would translate to the English pronoun "it": den for common gender words and det for neuter gender words. Both are gender-neutral in the sense of not referring to male or female, but they are not used to refer to human beings except in specific circumstances.[1]

History of usage

Attempts to introduce hen as a gender-neutral pronoun date back to 1966 when linguist Rolf Dunås suggested it in the regional newspaper Upsala Nya Tidning. In 1994, it was again proposed by linguist Hans Karlgren in the national newspaper Svenska Dagbladet as a practical alternative to more complicated literary alternatives.[2] In 2007, the feminist cultural magazine Ful[3] became the first periodical to adopt a consistent usage of hen.[4] By 2009, Nationalencyklopedin, the modern standard Swedish encyclopedia, had created an article about hen describing it as a "suggested gender-neutral personal pronoun instead of hon and han".[5]

In January 2012, the children's book Kivi och Monsterhund ("Kivi and Monster Dog") by Jesper Lundqvist was published. The book consistently used hen instead of han or hon and sparked a lively media debate.[6] In the February 2012 issue of Nöjesguiden, a Stockholm-based arts and entertainment monthly, hen was used consistently in all texts with the exception of direct quotes.[7] By late 2012, the word had generated so much publicity that Hufvudstadsbladet, Finland's largest Swedish-language newspaper by circulation, declared that "hen is here to stay".[8]

In November 2012, Swedish linguist Per Ledin made a survey of the use of hen in a corpus of Swedish blogs. His conclusion was that use among bloggers had been rising steadily from 2009 to 2012 and that it should be considered as an established word. However, hen accounted for just 0.001% of total usage of personal pronouns.[9]

The airline Norwegian employed the term in an ad campaign in 2012 as a tongue-in-cheek provocation with the slogan "The businessHEN's airline".[10][11] By late 2012, hen began to see use in official documents in some government agencies. The Court of Appeal for Lower Norrland applied the term in a ruling on official misconduct by a police officer.[12]

Hen appeared in an official political context for the first time in February 2013 when Swedish Minister for Gender Equality Maria Arnholm used it in a debate in the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament. In commenting on the debate afterwards, Arnholm described the word as "a practical way of simplifying" and "a smart way of developing language".[13] By 2013, Boden Municipality had adopted manuals of style to be used by their employees in an official context where hen was recommended "to avoid repetition of he/she in texts where sex is unclear or where we wish to include both sexes".[14]

By early 2014, hen had become an established term both in traditional media and among bloggers. The language periodical Språktidningen concluded that the instances of usage had gone from one instance for every 13,000 uses of hon/han to just under 1 in 300.[15] In late July 2014, the Swedish Academy announced that in April 2015, hen would be included in Svenska Akademiens ordlista, the most authoritative glossary on the Swedish language. Its entry will cover two definitions: as a reference to individuals belonging to a specified sex or third gender, or where the sex is not known.[16] In May 2015, hen was introduced in legal text (the driver's license law), in the self-ruling area Åland, a part of Finland which is officially Swedish-speaking.[17]

Recommendations

While the Swedish Language Council, the primary regulatory body of the Swedish language, suggests hen as one of several gender-neutral constructions, the word is not necessarily recommended above the alternatives. Rather, the Council advises the reader to use whichever construction is more contextually apt, considering the target audience. Alternatives to hen include den, equivalent to English it; rewriting as plural, which is ungendered in Swedish much like in English; repeating the noun instead of using a pronoun or using han eller hon ("he or she").[18] The council also recommends against using the object form henom ("her/him") with the reasoning that it is too similar to honom ("him"), which undermines the gender-neutral intention of the word, and that the case system on which the form is based is a remnant that is no longer used in Swedish; hen is instead recommended as both the subject and object form (as in jag såg hen; "I saw him/her") while hens is the recommended possessive form (i.e. "her(s)/his").[19]

After the use of hen by the Minister for Gender Equality, and following a meeting of the Speaker of the Riksdag together with party representatives, the Parliament made an official announcement that hen should not be used in official government documents, but that individual members of parliament are free to use it in spoken debates and written motions.[20] A handful of other authorities, such as the Equality Ombudsman and the National Financial Management Authority, use the pronoun routinely.[21]

Debate

From an early stage, hen has generated controversy and reactions in media. In 2010, the early use of the word prompted reactions of ridicule and skepticism. Columnist Lisa Magnusson taunted it as a "mega-feminist piece of poultry",[22] In early 2012, a series of interviews and articles about the use of hen in Dagens Nyheter, one of Sweden's leading newspapers, generated widespread debate. Referring to young children as hen was considered especially controversial, sparking critical reactions from the general public, officials within public daycare and media pundits.[23]

In September 2012, Dagens Nyheter issued a ban on the use of hen in its articles on the advice of chief editor Gunilla Herlitz. As a reaction to this, journalist and programmer Oivvio Polite created the website dhen.se,[24] a site that mirrored the content of the paper's online edition, but with all instances of han and hon replaced with hen. An employee at Dagens Nyheter reacted by filing a complaint to the police against dhen.se for violating Swedish copyright law, but later retracted his accusation when the newspaper's management proved unwilling to pursue legal action.[25]

The most controversial aspect of the use of hen has been vis-à-vis young children, especially in public schools. Egalia, a preschool in Södermalm, an upper middle-class borough in central Stockholm, had been at the forefront of gender-neutral pedagogy, and quickly adopted the use of hen. This policy sparked debate and controversy in Sweden and received widespread attention in international media in 2011–2012.[26][27][28][29]

See also

| Look up hen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Spivak pronoun

- Gender-neutral language

- Gender-neutral pronoun

- Feminist language planning

- Lavender linguistics

Notes

- Pettersson (1996), pp. 154–155

- Svenska Dagbladet, 8 March 2012.

- See also the official manifesto by Ful regarding the use of hen.

- Margret Atladottir, "När könet är okänt", Nöjesguiden, 29 February 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Språkrådet, 15 March 2012. "Hen inte nytt i Nationalencyklopedin Archived 2013-01-29 at the Wayback Machine"; Nina Bahadur, "Swedish Gender-Neutral Pronoun, 'Hen,' Added To Country's National Encyclopedia", Huffington Post, 11 April 2013.

- Adrianna Pavlica, "Så började debatten om hen" Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine Göteborgsposten, 29 February 2012

- Margret Atladottir, "Därför använder vi ordet hen", Nöjesguiden, 29 February 2012.

- Matts Lindqvist, "Hen har kommit för att stanna". Hufvudstadsbladet, 19 September 2012.

- Per Ledin, "Hen i bloggosfären: spridningsmönster". På svenska, 28 November 2012.

- Språktidningen, "Nu debatterar vi hen igen!" 11 September 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- https://www.dagensmedia.se/marknadsforing/kampanjer/norwegian-vander-sig-till-hen-6132158

- Språktidningen, "Hens uppgång har nått hovrätten" 14 December 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Lova Olsson (2013-02-13). "Arnholm lanserar "hen" i riksdagen" (in Swedish). Svd.se. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- Original quote: "för att undvika upprepningar av han/hon i texter där vi inte vet kön eller vill omfatta bägge könen"; Språktidningen, "Så funkar klarspråk i Boden", 30 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Språktidningen, "Så snabbt ökar hen i svenska medier", 18 mars 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Benaissa, Mina (29 July 2014). "Svenska Akademiens ordlista inför hen". Sveriges Radio.

- Ja till hen i åländsk lagtext Archived 2015-05-25 at the Wayback Machine HBL.fi (Swedish) 25 May 2015

- "Frågelådan: Hur gör jag för att referera till personer utan att behöva ange kön?" [FAQ: How do I refer to people without specifying gender?] (in Swedish). Swedish Language Council. 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- "Hur använder man pronomenet hen?" [How to use the pronoun hen?] (in Swedish). Swedish Language Council. 2014-08-25. Archived from the original on 2015-05-29. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- Nyheter 00.53 (2013-03-05). "Riksdagen bör avstå från hen". DN.SE. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- "Hen blir allt vanligare hos myndigheter" [Hen becomes more common with authorities] (in Swedish). Swedish Language Council. 2014-08-25. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- Lisa Magnusson, "Hen – ett dumfeministiskt fjäderfä", Aftonbladet 19 January 2010

- Dalén, Karl (24 February 2012). "Starka reaktioner efter intervjuer om "hen"". Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- A play on the URL of Dagens Nyheter, dn.se, and its acronym "DN" which is pronounced [de: ɛn] in Swedish.

- Dante Thomsen (2012-09-10). "Herlitz inför hen-förbud". Dagens Media. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- Dave McGinn, "You're a hen, I'm a hen: gender-neutral pronoun gains ground in Sweden" The Globe and Mail, 13 April 2012

- John Tagliabue, "Swedish School’s Big Lesson Begins With Dropping Personal Pronouns", The New York Times, 12 November 2012

- Marie-Charlotte Maas, "Sei, was du willst", Die Zeit , 24 August 2012

- Soffel, Jenny. "'Gender-neutral' pre-school accused of mind control", The Independent. 3 July 2011.

References

- Pettersson, Gertrud (1996) Svenska språket under sjuhundra år: en historia om svenskan och dess utforskande. Studentlitteratur, Lund. ISBN 91-44-48221-3, OCLC 36130929