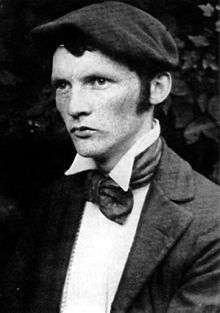

Heinrich Vogeler

Heinrich Vogeler (December 12, 1872 – June 14, 1942) was a German painter, designer, and architect, associated with the Düsseldorf school of painting.

Early life

He was born in Bremen, and studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1890–95. His artistic studies during this period included visits to Belgium and Italy.

Vogeler was a central member of the original artist colony in Worpswede, which he joined in 1894. In 1895 Vogeler bought a cottage there and planted many birch trees around it, which gave the house its new name: Barkenhoff (Low German for Birkenhof, or "birch tree cottage"). In 1901, he married Martha Schröder.

He made book illustrations in an art nouveau style, and executed decorative paintings for the town hall of Bremen shortly before traveling to Ceylon in 1906. During a trip to Łódź, he studied Maxim Gorky's works, which resulted in the development of a deep sympathy for the working class. This feeling reached further heights when he saw life in the slums of Glasgow and Manchester during a trip.[1] In 1908 he and his brother Franz founded the 'Worpsweder Werkstätte', which produced household objects. His paintings increasingly reflected his sympathy for the working class.

During the First World War

He volunteered for military service in World War I in 1914, and he was sent to the eastern front in 1915. Vogeler came to know of the Bolsheviks ideology during his time at the front as well as through his trips to Poland, Romania, Dobrudscha and Russia.[1] After he made a written appeal for peace to the German Emperor, he was briefly sent to a mental hospital in Bremen before being discharged from military service.

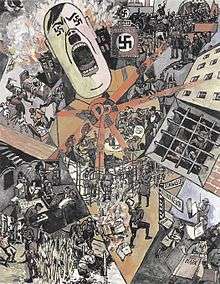

Political activism

After the war he became a pacifist. During the German Revolution of 1918–19, he joined the workers' and soldiers' council of the Bremen Soviet Republic, together with his friend Curt Stoermer. He joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), but when it split, he joined the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD). He was close to Franz Pfemfert, who published Die Aktion.[2] After the end of the Revolution, he was arrested for some time. It was at that time that he and his wife Martha were divorced. From that point on, he wanted to work ideologically, and the romanticism of his earlier work gave way to proletarian content. In 1931 Vogeler and his second wife Zofia "Sonja" Marchlewska, daughter of Julian Marchlewski, emigrated to Russia. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union he along with other German citizens was deported in 1941 to Kazakhstan by the Soviet authorities, and died there in 1942.

KPD leader Wilhelm Pieck apparently had wanted to prevent his deportation, but Vogeler himself refused privileged treatment. As his wife Zofia and son Jan were Polish citizens they were drafted instead of being deported with him. Jan soon became a founding member of the National Committee for a Free Germany and after a long post-war academic career in Moscow died in his father's Worpswede in 2005. Zofia emigrated to Poland and died in Warsaw in 1983.

Meanwhile, the Barkenhoff became a children's home. It was recently restored and has re-opened as a Heinrich Vogeler Museum in 2004.

Late works from Heinrich Vogeler's ourvre appear to have some Egyptian influences, particularly in images such as Der Aufbau der zentralasiatischen Sowjetrepubliken (1927). The influence remains in Worpswede amongst particular sculptures, and market performances.

Gallery

Abendsonne im Moor, before 1903

Abendsonne im Moor, before 1903 Frühlingsabend 1901

Frühlingsabend 1901 Der Moorgraben

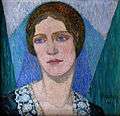

Der Moorgraben Johanna Schulze

Johanna Schulze_1912.jpg) Die Erwartung (Träume II)

Die Erwartung (Träume II) Frühling

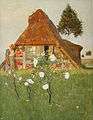

Frühling Frühlingshecken im Bauerngarten

Frühlingshecken im Bauerngarten_c1900.jpg) Sehnsucht (Träumerei)

Sehnsucht (Träumerei) Sommergarten

Sommergarten Straßenszene in Kalusz

Straßenszene in Kalusz Versammlung kurdischer Hirten vom Kolchos Lenin

Versammlung kurdischer Hirten vom Kolchos Lenin Träume

Träume Träume

Träume Verkündigung an die Hirten

Verkündigung an die Hirten Die rote Marie/Red Marie (Marie Griesbach)

Die rote Marie/Red Marie (Marie Griesbach)

References

- "Heinrich Vogeler". Art Directory. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- Bourrinet, Phillippe. "Lexikon des deutschen Rätekommunismus" (PDF). lib Com. Verlag moto propri. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

External links

- Works by Heinrich Vogeler at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Heinrich Vogeler at Internet Archive

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heinrich Vogeler. |