Christian Friedrich Hebbel

Christian Friedrich Hebbel (18 March 1813 – 13 December 1863) was a German poet and dramatist.

Christian Friedrich Hebbel | |

|---|---|

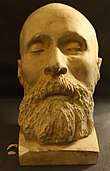

Portrait (1851) by Carl Rahl | |

| Born | 18 March 1813 Wesselburen, Dithmarschen, Holstein |

| Died | 13 December 1863 (aged 50) Vienna, Austrian Empire |

| Occupation | poet and dramatist |

| Nationality | Germany |

| Notable awards | Schiller Prize |

Biography

Hebbel was born at Wesselburen in Dithmarschen, Holstein, the son of a bricklayer. He was educated at the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums, a grammar school in Hamburg, Germany. Despite his humble origins, he showed a talent for poetry,[1] resulting in the publication in the Hamburg Modezeitung, of verses which he had sent to Amalie Schoppe (1791–1858), a popular journalist and author of nursery tales. Through her patronage, he was able to go to the University of Hamburg.

A year later he went to Heidelberg University to study law, but gave it up and went on to the University of Munich, where he devoted himself to philosophy, history and literature. In 1839, Hebbel left Munich and walked all the way back to Hamburg, where he resumed his friendship with Elise Lensing, whose self-sacrificing assistance had helped him over the darkest days in Munich. In the same year he wrote his first tragedy, Judith (1840, published 1841), which in the following year was performed in Hamburg and Berlin and made his name known throughout Germany.[1]

In 1840, he wrote the tragedy Genoveva, and the following year finished a comedy, Der Diamant, which he had begun at Munich. In 1842 he visited Copenhagen, where he obtained from King Christian VIII a small travelling studentship, which enabled him to spend some time in Paris and two years (1844–1846) in Italy. In Paris he wrote his fine "tragedy of common life", Maria Magdalena (1844). On his return from Italy Hebbel met in Vienna two Polish noblemen, the brothers Zerboni di Sposetti, who in their enthusiasm for his genius urged him to remain, and supplied him with the means to mingle in the best intellectual society of the Austrian capital.[1]

Hebbel's old precarious existence now became a horror to him, and he made a deliberate breach with it by marrying (in 1846) the beautiful and wealthy actress Christine Enghaus, giving up Elise Lensing (who remained faithful to him until her death), on the grounds that "a man's first duty is to the most powerful force within him, that which alone can give him happiness and be of service to the world": in his case the poetical faculty, which would have perished "in the miserable struggle for existence". This "deadly sin," which, "if peace of conscience be the test of action," was, he considered, the best act of his life, established his fortunes. Elise, however, still provided useful inspiration for his art. As late as 1851, shortly after her death, he wrote the little epic Mutter und Kind, intended to show that the relation of parent and child is the essential factor which makes the quality of happiness among all classes and under all conditions equal.[1]

Long before this Hebbel had become famous, German sovereigns bestowed decorations upon him; in foreign capitals he was feted as the greatest of living German dramatists. From the grand-duke of Saxe-Weimar he received a flattering invitation to take up his residence at Weimar, where several of his plays were first performed. He remained, however, at Vienna until his death.[1]

Works

Besides the works already mentioned, Hebbel's principal tragedies are:[1]

- Herodes and Mariamne (1850)[1]

- Julia (1851)[1]

- Michel Angelo (1851)[1]

- Agnes Bernauer (1855)[1]

- Gyges and His Ring (1856)[1]

- Die Nibelungen (1862), his last work (a trilogy consisting of a prologue, Der gehörnte Siegfried, and the tragedies, Siegfrieds Tod and Kriemhilds Rache), which won for the author the Schiller Prize.[1]

Of his comedies Der Diamant (1847), Der Rubin (1850) and the tragi-comedy Ein Trauerspiel in Sizilien (1845), are the more important, but they are heavy and hardly rise above mediocrity. All his dramatic productions, however, exhibit skill in characterization, great glow of passion, and a true feeling for dramatic situation; but their poetic effect is frequently marred by extravagances which border on the grotesque, and by the introduction of incidents the unpleasant character of which is not sufficiently relieved. In many of his lyric poems, and especially in Mutter und Kind, published in 1859, Hebbel showed that his poetic gifts were not restricted to the drama.[1]

Hebbel's short stories are often wry and witty observations of society. His well-known story "The master tailor Nepomuk Schlägel in the search for joy" has been published in English.[2]

His collected works were first published by E. Kuh in 12 volumes at Hamburg, 1866–1868.[1]

Music

Some of Hebbel's works were set to music, such as his poem Requiem by Peter Cornelius and in Max Reger's Hebbel Requiem. Reger set his poem "Die Weihe der Nacht" for voice, choir and orchestra. Robert Schumann's opera Genoveva is based on a play of Hebbel.

In 1872 Samuel de Lange used Hebbel's poem "Ein frühes Liebesleben" in an unusual instrumentation for voice, string quartet and harp. An arrangement with piano instead of harp was made during a centennial revival of Samuel and Daniël de Lange's music.[3]

Eduard Lassen wrote incidental music to Die Nibelungen in 1873. In 1878/79 Franz Liszt combined music from the Die Nibelungen setting with excerpts from Lassen's incidental music to Goethe's Faust, in a single piano transcription, Aus der Musik zu Hebbels Nibelungen und Goethes Faust (S.496).

In 1922 Emil von Reznicek composed an opera Holofernes after Hebbel's Judith und Holofernes.

The poem "Dem Schmerz sein Recht" was set to music by Alban Berg in 4 Gesänge, Op. 2, No 1.

Films

- Glutmensch (A man aglow, 1975), 90 min.; writer and director: Jonatan Briel; Production: SFB and Literarisches Berliner Kolloquium; Plot: Werner Brunn plays Friedrich Hebbel, who is confined to his sickbed on his 50th birthday, and recalls his youth in his feverish dreams.

References

Notes

-

- https://sites.google.com/site/bartholomewbegley/friedrich-hebbel-the-master-tailor-nepomuk-schl%C3%A4gel-in-the-search-for-joy

- "Samuel de Lange, "Ein frühes Liebesleben"". pythagoraskwartet.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2017-03-24.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christian Friedrich Hebbel |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Friedrich Hebbel. |

- Works by Friedrich Hebbel at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Friedrich Hebbel at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Christian Friedrich Hebbel at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Complete Poems of Friedrich Hebbel (in German)