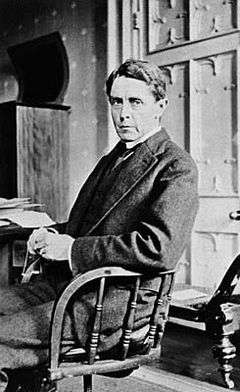

Harrison Moore

Sir William Harrison Moore KBE CMG (30 April 1867 – 1 July 1935), usually known as Harrison Moore or W. Harrison Moore, was an Australian lawyer and academic who was a professor at the University of Melbourne and the third dean of the Melbourne University Law School.

Early life and education

Moore was born in London, England in 1867, the son of printer John Moore and of Jane Dorothy Moore, née Smith. Moore left school at the age of 17, and worked as a journalist in the gallery at the British House of Commons. With the help of the Barstow law scholarship from the Council of Legal Education, Moore gained entry at King's College at the University of Cambridge in 1887, and was also admitted to the Middle Temple. In 1891 Moore graduated from Cambridge with a Bachelor of Arts degree, and from the University of London with a Bachelor of Laws, winning both the George Long prize and the Chancellor's medal from King's College.[1][2]

He was admitted to the English bar by the Middle Temple later that year. He read under Thomas Edward Scrutton (a future Judge of the Court of Appeal), and intended to practise in the area of commercial law, but his poor health forced him to move to Australia, seeking a better climate.[2]

Melbourne University Law School

Moore moved to Melbourne, Victoria in 1892, having been appointed as the third Dean of the Law School of the University of Melbourne, succeeding Edward Jenks. Moore was somewhat controversial as a new dean, proposing that Roman law (a strong influence on the civil law system predominant in Europe, but less important to the common law system in Australia) no longer be taught at the University, and the removal of legal procedure as a separate undergraduate course.[3]

The Law School under Moore opened its doors to practising lawyers in addition to academics, visiting lecturers in the year of 1908 including people such as High Court Justice H. B. Higgins, Chief Justice of Victoria Sir John Madden, and judge of the Supreme Court of Victoria Leo Cussen.[4] The School, located then in what is now known as the "Old Law" building, struggled for room and resources, Moore having to contribute some of his personal library for the use of students, and some lectures having to be held in the Supreme Court building in the city.[4]

Notable students

Moore's students at the University included future Chief Justice of Australia Owen Dixon, future Prime Minister of Australia Robert Menzies and historian Keith Hancock. Dixon described Moore as having "a gentle manner, learning infused with the true spirit of liberalism, a complete grasp of legal principle to the exclusion of all that was mere dogma and a lively interest in constitutional and legal development."[4] Hancock regarded Moore's lectures, which mixed elements of political philosophy and legal history with the teaching of the law, as "the best course that I have ever known at any of my many universities."[3]

Federation of Australia

Moore was an enthusiastic supporter of Federation. Following the Corowa Conference he soon became an expert on the various draft constitutions, and by the time of the Second Constitutional Convention in Adelaide, South Australia in 1897, Moore had become "an acknowledged authority on the drafts and was used as a human reference library by convention members."[3] Moore was respected by his students as an expert without parallel in federalism, not only for his mastery of the material but for his dedication to learning the theories which were largely unknown to him before coming to Australia; federalism being a crucial part of the legal systems in the United States and Canada but not part of a Cambridge legal education.[4] In 1902 he published his first major work, The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia,[5] which was both an examination of the Constitution of Australia and a history of the Federation movement itself.

Marriage

On 10 November 1898, Moore married Edith Eliza à Beckett, daughter of a judge of the Supreme Court of Victoria – and former lecturer at the University of Melbourne – Thomas à Beckett. Edith was a passionate advocate of women's suffrage in Australia and helped to found the Queen Victoria Hospital in central Melbourne.[3]

Later career

In 1899, Moore prepared a report for the University calling for greater practical involvement with the business community, in addition to the formal and theoretical elements of the curriculum, which, despite not being immediately adopted, formed the basis for the University's commerce degree when it was introduced in 1925.[3] Moore published several more books in the early 1900s, including Imperial and Local Taxation in 1902 and The Act of State in Relation to English Law[6] in 1906.

From 1907 to 1910, Moore served as an official adviser on constitutional matters to the Government of Victoria, serving under Premiers Sir Thomas Bent and John Murray, and advised several conservative leaders in federal politics. From time to time, Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson also consulted Moore on questions of constitutional law.[3] In 1917, Moore was made a Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) and a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1925.

In the early 1920s, Moore worked with Leo Cussen on preparatory work the latter's second consolidation of Victorian law, particularly with respect to the Imperial Acts Application Act 1922.[3] Cussen would later complete the consolidation in 1928.

Moore retired from the Law School in 1927, and was appointed professor emeritus the following year. In May 1928, and again in 1929 and 1930, Moore was appointed as the Australian delegate to the League of Nations. He had previously contributed to the League's efforts to codify international law, having attended universities throughout Europe in 1928, after participating in the Rome conference that revised the Berne Convention.[3] Moore was also part of the Australian delegation to the Imperial Conference of 1930, which ultimately led to the Statute of Westminster. As a member of the Australian executive committee of the Institute of Pacific Relations, he led a delegation to Shanghai, China in 1931 to attend a conference on Pacific relations.

Shortly before his death in 1935, Moore was elected an honorary member of the Society of Comparative Legislation (now part of the British Institute of International and Comparative Law). His last work was a paper for the Society's journal, submitted shortly before his death, on the topic of inter-governmental legal actions within Australia and Canada.[7]

Death

Moore died in 1935 in the Melbourne suburb of Toorak, and was survived by his wife. They had no children.

References

- "Moore, William Harrison (MR887WH)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- C. E. A. B. (1935). "William Harrison Moore". Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law. Society of Comparative Legislation. 17 (third series) (4): 161–162.

- Re, Loretta (1986). "Moore, Sir William Harrison (1867 - 1935)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. 10: 573–575. ISBN 0-522-84327-1. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- Ayres, Philip (2003). Owen Dixon. Carlton, Victoria: The Miegunyah Press. p. 400. ISBN 0-522-85045-6.

- Moore, William Harrison (1902). The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia. London, England: John Murray. pp. 395.

- Moore, William Harrison (1906). The Act of State in Relation to English Law. London, England: John Murray.

- Moore, William Harrison (1935). "The Federations and Suits Between Governments". Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law. Society of Comparative Legislation. 17 (third series) (4): 163–209.