Hachijō-jima

Hachijō-jima (八丈島) is a volcanic Japanese island in the Philippine Sea. It is about 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of the special wards of Tokyo, to which it belongs. It is part of the Izu archipelago and within the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park. Its only municipality is Hachijō. On 1 March 2018, its population was 7,522 people living on 63 km2. The Hachijō language is spoken by some inhabitants, but it is considered an endangered language and the number of speakers is unknown. The island has been inhabited since the Jōmon period, and was used as a place of exile during the Edo period. In modern times, it has been used for farming sugarcane and housing a secret submarine base during World War II; it is now a tourist destination within Japan.

| Native name: 八丈島 | |

|---|---|

Hachijō-fuji and the smaller island of Hachijō-kojima (left) as seen from Osaka Tunnel, 2018 | |

Hachijō-jima | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Izu Islands |

| Coordinates | 33°06′34″N 139°47′29″E |

| Archipelago | Izu Islands |

| Area | 62.52 km2 (24.14 sq mi) |

| Length | 14 km (8.7 mi) |

| Width | 7.5 km (4.66 mi) |

| Coastline | 58.91 km (36.605 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 854.3 m (2,802.8 ft) |

| Administration | |

Japan | |

| Prefecture | Tokyo |

| Subprefecture | Hachijō Subprefecture |

| Town | Hachijō |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 7522 (March 2018) |

Hachijō-jima receives about 3,000 millimetres (120 in) of precipitation annually. With a humid subtropical climate, and an average high temperature of 21 °C (70 °F), the island and the surrounding oceans support a wide variety of sea life, birds, mammals, plants, and other life. The tallest peak within the Izu Islands, a Class-C active volcano, is found there. Transportation to the island is either by air or ferry. There are many Japanese-style inns, hot spring resorts, and hotels to accommodate tourists and visitors. The island is a popular destination for surfers, divers and hikers. It has several local variations on Japanese foods, including shimazushi and kusaya, as well as many dishes that include the local plant ashitaba.

Geography

Location

Hachijō-jima is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of the Izu Peninsula[1]—or about 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of Tokyo[2]—in the Philippine Sea.[3] The smaller island of Hachijō-kojima is 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) northwest of Hachijō-jima,[4] and can be seen from the top of Nishiyama.[2] The Pacific Ocean is to the east of the island, with Mikura-jima about 79 kilometres (49 mi) to the north and Aogashima about 64 kilometres (40 mi) to the south. The island is within the boundaries of Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park.[5]

Municipalities

The only municipality on the island is the town of Hachijō,[4] which encompasses both Hachijō-jima and the neighbouring Hachijō-kojima, though no one lives on the latter.[4] The town is divided into five areas: Mitsune (三根), Nakanogo (中之郷), Kashitate (樫立), Sueyoshi (末吉), and Ōkago (大賀郷).[4]

Population

The population of Hachijō-jima on 1 March 2018 was 7,522.[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

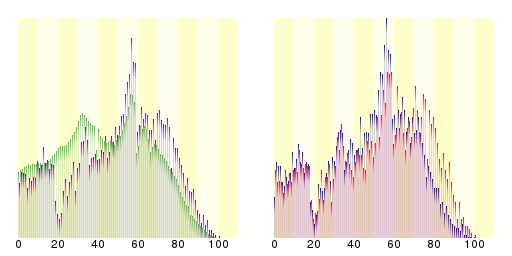

| Comparison of Population Distribution between Hachijō-jima and Japanese National Average | Population Distribution by Age and Sex in Hachijō-jima | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

■Hachijō-jima ■Japan (average) |

■Male ■Female | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 Census, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications - Statistics Department | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Language

The Hachijō language is the most divergent form of Japanese; it is the only surviving descendant of Eastern Old Japanese.[7] The number of speakers is not certain; it is on UNESCO's list of endangered languages,[8] and is likely to be extinct by 2050 if counter-measures are not taken.[9]

Flora and fauna

Since November 2015, humpback whales have been observed gathering around the island, far north from their known breeding areas in the Bonin Islands. All breeding activities except for giving births have been confirmed, and research is underway by the town of Hachijō and the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology to determine whether Hachijō-jima may become the northernmost breeding ground in the world, and possible expectations for opening a future tourism attraction.[10] Whales can be viewed even from hot springs.[11] Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, likely (re)colonised from Mikura-jima, also live around the island,[12] among other cetaceans such as false killer whales,[13] sperm whales,[14] and orcas (being sighted during humpback whale research in 2017).[15]

The waters around the island are important for the nourishment of green sea turtles.[16]

The island is home to bioluminescent mushrooms, including Mycena lux-coeli—meaning "heavenly light mushrooms"—and Mycena chlorophos. M. lux-coeli are widely found and for decades were believed only to exist on the island.[17] The local name for the mushrooms is hato-no-hi, literally "pigeon fire".[17]

The Izu thrush makes its home on the island, as does the Japanese white-eye.[4][18] Hamatobiuo (a type of flying fish) is found in the waters surrounding the island.[4][19] Many different plants are native to the island, including the pygmy date palm, aloe, freesia, hydrangea, hibiscus, Oshima and Japanese cherry, and bird of paradise.[4][18]

Climate

Hachijō-jima has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with very warm summers and mild winters. Precipitation is abundant throughout the year, but is somewhat lower in winter.[20]

| Climate data for Hachijō-jima | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

29.8 (85.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.7 (69.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 190.0 (7.48) |

202.9 (7.99) |

308.6 (12.15) |

226.8 (8.93) |

251.2 (9.89) |

380.5 (14.98) |

224.6 (8.84) |

179.3 (7.06) |

338.9 (13.34) |

465.9 (18.34) |

250.7 (9.87) |

182.9 (7.20) |

3,202.3 (126.07) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 15.8 | 15.0 | 18.3 | 13.8 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 15.6 | 17.4 | 14.3 | 14.8 | 180 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 68 | 69 | 80 | 86 | 96 | 92 | 86 | 86 | 82 | 73 | 70 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 85.7 | 83.8 | 122.3 | 133.5 | 135.6 | 91.8 | 118.5 | 170.0 | 134.2 | 106.8 | 108.1 | 108.2 | 1,398.5 |

| Source: JMA (1981–2010) [21] | |||||||||||||

Geology

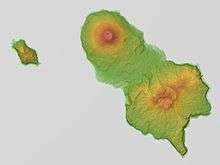

Hachijō-jima is a compound volcanic island that is 14.5 kilometres (9 miles) in length with a maximum width of 8 kilometres (5 miles). The island is formed from two stratovolcanoes.[22] Higashi-yama (東山)—also called Mihara-yama (三原山)—has a height of 701 metres (2,300 ft) and was active from 100,000 BC to around 1700 BC.[23] It has eroded flanks and retains a distinctive caldera.[23][24]

Nishi-yama (西山)—also called Hachijō-fuji (八丈富士)—has a height of 854.3 metres (2,803 ft). It is the highest point on the island and the tallest peak in the Izu island chain.[23][25][26] The summit is occupied by a shallow caldera with a diameter of 400 metres (1,300 feet) and a depth of around 50 metres (160 feet). It is rated as a Class-C active volcano[27] by the Japan Meteorological Agency with recent eruptions recorded in 1487, 1518–1523, and 1605, with seismic activity as recently as 2002.[28] Between these two peaks are over 20 flank volcanoes and pyroclastic cones.[23]

History

Hachijō-jima has been inhabited since at least the Jōmon period, and archaeologists have found magatama and other remains.[29] Under the Ritsuryō system of the early Nara period, the island was part of Suruga Province. It was transferred to Izu Province when Izu separated from Suruga in 680. During the Heian period, Minamoto no Tametomo was banished to Izu Ōshima after a failed rebellion, but per a semi-legendary story, escaped to Hachijō-jima, where he attempted to establish an independent kingdom.[30]

During the Edo period, the island became known as a place of exile for convicts,[1] most notably Ukita Hideie,[31] a daimyō who was defeated at the Battle of Sekigahara. Originally the island was a place of exile mainly for political figures, but beginning in 1704 the criteria for banishment were broadened. Crimes punishable by banishment included murder, theft, arson, brawling, gambling, fraud, jailbreak, rape, and membership of an outlawed religious group. Criminals exiled to the island were never told the length of their sentences, and the history of the island is filled with foiled escape attempts. Its use as a prison island ended during the Meiji Restoration: after a general amnesty in 1868 most of the island's residents chose to move to the mainland; however, the policy of banishment was not officially abolished until 1881.[32]

Former U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant visited the island during his 1877 world tour. The island's residents were aware of his exploits in the American Civil War and gave him a jubilant welcome. He was ceremonially adopted by the village chief, being given the name Yūtarotaishō; meaning "courageous general" in the local dialect, and was presented with prayer beads made with pearls and gemstones. He declared that the island's residents were the "friendliest people in the Pacific".[33]

In 1900, pioneers from Hachijō became the first inhabitants of the Daitō Islands, where they established a sugarcane farming industry. The Hachijō language is still spoken on the islands to this day.[34]

During World War II, the island was regarded as a strategic point in the defense of the ocean approaches to Tokyo; and in the final stages of the war, a base of operations for the Kaiten suicide submarines was founded on the southern coast.[35] From the end of the war through the 1960s, the government made attempts to promote Hachijō-jima as the "Hawaii of Japan" to encourage tourist development,[36] and tourism remains a large component of the island's economy.[4]

There is a small mystery regarding the history of Hachijō-jima, of potential significance to the history of "women's rights". Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, a well known autobiographer from the early 20th Century states in A Daughter Of The Samurai that the island was commonly known in Japan during her childhood for being a place where standard gender roles were reversed; women did heavy field work and "made laws", and men tended the home and children. The mystery comes from the fact that no other current source mentions this today. A brief quote to illustrate the significance of the information:

" 'We have a whole island where women do men's work from planting rice to making laws.'

'What do the men do?'

'Cook, keep house, take care of the children, and do the family washing.'

'You don't mean it!' exclaimed Miss Helen, and she sat down again.

But I did mean it, and I told her of Hachijo, a little island about a hundred miles off the coast of Japan, where the women, tall, handsome, and straight, with their splendid hair coiled in an odd knot on the top of the head, and wearing long, loose gowns bound by a narrow sash tied in front, work in the rice fields, make oil from camellia seeds, spin and weave a peculiar yellow silk, which they carry in bundles on their heads over the mountains, at the same time driving tiny oxen, not much larger than dogs, also laden with rolls of silk to be sent to the mainland to be sold. And in addition to all this, they make some of the best laws we have, and see that they are properly carried out. In the meantime, the older men of the community, with babies strapped to their backs, go on errands or stand on the street gossiping and swaying to a sing-song lullaby; and the younger ones wash sweet potatoes, cut vegetables, and cook dinner; or, in big aprons, and with sleeves looped back, splash, rub, and wring out clothes at the edge of a stream."[37] LCC Card No 66-15849, pp 202–203

Transportation

Hachijō-jima is accessible both by aircraft and by ferry. In 2010 a pedestrian ferry would leave Tōkyō once every day at 10:30 pm, and arrive at Hachijō-jima at 8:50 am the following day. Air travel to Hachijojima Airport takes 45 minutes from Tōkyō International Airport (Haneda).[2] In 2000, there were three metropolitan roads on Hachijō-jima: 215 (formally, 東京都道215号八丈循環線),[38][39] 216 (都道216号神湊八重根港線, 8.3 km),[38][40] and 217 (東京都道217号汐間洞輪沢港線).[38]

Tourism

Notable landmarks

The island is home to the Hachijo Royal Resort, a now-abandoned French baroque-style luxury hotel that was built during the tourism boom of the 1960s. When the hotel was built in 1963 it was one of the largest in Japan, and attracted visitors from all over the country. The hotel was finally closed in 2006 due to declining tourism to the island. As of April 2016, the grounds were overgrown and the building severely dilapidated.[36][41]

The Hachijō-jima History and Folk Museum (八丈島歴史民俗資料館, Hachijō-jima Rekishi Minzoku Shiryōkan) contains displays covering the history of the island, local industries, as well as the animals and plants found on and around the island.[42][43] The Hachijō Botanical Park (八丈植物公園, Hachijō Shokubutsu Kōen) is a botanical and animal park next to the Hachijojima Visitors Center.[42][43]

Activities and accommodation

In 2005, accommodation on Hachijō-jima was plentiful, with many Japanese-style inns, hot spring resorts, campsites, and several larger hotels.[44] Hachijō-jima is popular with surfers, with three reef breaks and consistently warmer water than mainland Japan because of the Kuroshio Current.[32] Because Hachijō-jima is a volcanic island, there are several black sandy beaches, including one next to the main harbour of Sokodo.

Hachijō-jima's scuba diving points were regarded in 2008 as many and varied, and as including one of the top five diving spots in Japan.[45]

Hachijō-jima is known for its hiking trails, waterfalls, and natural environment. Other activities for visitors include visiting the Botanical Park, exploring wartime tunnels, and hiking to the top of Hachijō-fuji.[43]

Kihachijō, a naturally yellow silk fabric, is woven on the island.[1] One of the workshops is open to tourists.[43] The Tokyo Electric Power Company operates a free museum at its geothermal power plant.[46]

Food

Hachijō-jima is famous both for its sushi—known locally as shimazushi—and for its kusaya (a dried and fermented version of hamatobiuo).[47][48] As well as being served with sake, the latter is used in many different recipes.[49]

Local cuisine also makes use of the ashitaba plant in dishes such as ashitaba soba and tempura.[2][49]

Gallery

Mt Hachijō-Fuji and Hachijō-Koshima island seen from the Noboryō Pass

Mt Hachijō-Fuji and Hachijō-Koshima island seen from the Noboryō Pass Tamaishigaki: walls built by convicts exiled on Hachijō-jima in the Edo Period

Tamaishigaki: walls built by convicts exiled on Hachijō-jima in the Edo Period The Karataki waterfall, in the hills around Mt. Mihara

The Karataki waterfall, in the hills around Mt. Mihara

Freesia Festival

Freesia Festival Aloe growing on Mt. Hachijō-Fuji

Aloe growing on Mt. Hachijō-Fuji- Hachijō-jima view

- View from the top of the rock at Kurosuna, Hachijō

See also

- Runin: Banished, a 2004 film about convicts exiled to Hachijō-jima and their attempts to escape

- Battle Royale, a 2000 film filmed on the neighbouring, uninhabited, Hachijō Kojima, although not set on the island

- List of islands of Japan

References

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). "Hachijō-shima". Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press Reference Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-674-00770-0. LCCN 2001052570. Translated by Käthe Roth.

- "Hachijo-jima – Floral Paradise". Hiragana Times. Japan. Feb 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard (1962). Sovereign and Subject. Ponsonby Memorial Society. p. 332.

- 八丈町の概要 [Overview of Hachijō] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- 人口 八丈町 [Population of Hachijō] (PDF) (in Japanese). Hachijō. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger - Hachijō". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Heinrich, Patrick (2012). The Making of Monolingual Japan: Language Ideology and Japanese Modernity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-84769-659-5.

- 八丈島ザトウクジラ調査について [Regarding the Hachijō-jima Humpback Whale Survey] (in Japanese). Town of Hachijō. 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 八丈島に今年もザトウクジラがやってきた! [This year too the whales came to Hachijō-jima!] (in Japanese). 23 March 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ミナミハンドウイルカ [Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin] (in Japanese). Hachijō-jima. 2 April 2001. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- オキゴンドウと接近遭遇 [Close encounters with false killer whales] (in Japanese). 八丈島情報サイト Boogen. 31 August 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 【ツアー報告】アホウドリに会いたい!東京~八丈島航路 2016年3月26日~27日 [Tour Report: I want to meet an albatross! Cruise from Tokyo to Hachijō-jima 26–27 March 2016] (in Japanese). ネイチャリングニュース (Naturing News). 26 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 八丈島観光協会 (28 May 2015). クジラ襲うシャチを撮影 知床・羅臼沖、観光船長も興奮 [Recording of a killer whale attack in the open sea while sightseeing near Shiretoko: The ship's captain too is excited] (in Japanese). YouTube. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 島田貴裕. 「八丈島周辺に生息するアオウミガメ」、亀田和成編、『日本のアオウミガメ』 (日本ウミガメ協議会, 2013), pp. 93–98. As cited in Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Identified by Japan: 沿岸域 12401 八丈島周辺 Archived 2017-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Bird, Winifred (11 June 2008). "Luminescent mushrooms cast light on Japan's forest crisis". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- 風景 [Scenery] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (eds.). "Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus japonicus (Franz, 1910)". World Register of Marine Species at Flanders Marine Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Hachijojima Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- "Hachijojima Climate Normals 1981–2010". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- "Hachijo-jima volcano". VolcanoDiscovery.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "八丈島 Hachijojima" (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- 中之郷 - 18 三原山 [Nakanogō: 18 Mihara-yama] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Ōtake, Mioko; Nakamura, Mitsuo (2015). Yama no Namaette Omoshiroi! 山の名前っておもしろい! (in Japanese). Jitsugyō no Nihonsha. p. 109. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27.

- 三根 3 八丈富士 [Mitsune: 3 Hachijō-fuji] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- 林豊; 宇平幸一 (17 April 2007). 活火山カタログの改訂と火山活動度による活火山の分類(ランク分け)について [The Revised List of Active Volcanoes in Japan and Classification (Ranking) of the Volcanoes Based on their Past 10,000 years of Activity] (PDF) (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. p. 51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- 八丈島 有史以降の火山活動 [Hachijō-jima Historically Recorded Volcanic Activity] (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Naumann, Nelly (2000). Japanese Prehistory: The Material and Spiritual Culture of the Jōmon Period. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-447-04329-8.

- Onuma, Hideharu; DeProspero, Dan; DeProspero, Jackie (1993). Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery. Tokyo: Kodansha International. p. 14. ISBN 978-4-7700-1734-5.

- Murdoch, James; Yamagata, Isoh (1996) [first pub. 1903]. A History of Japan. London: Routledge. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-415-15076-7.

- "Getting to Know Hachijo". Japanzine. Japan: Carter Witt Media. 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 588. ISBN 0-684-84926-7.

- Hayward, Philip; Long, Daniel (2013). "Language, music and cultural consolidation on Minami Daito". Perfect Beat. ISSN 1836-0343. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27.

- Hastings, Max (2008). Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944–45. New York: Knopf. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-307-27536-3.

- "The Rise and Unravelling of the Hachijo Royal Hotel Archived 2018-03-16 at the Wayback Machine", Ridgeline Images, 17 April 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Inagaki Sugimoto, Etsu. "A Daughter of the Samurai". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- 平成17年度道路交通センサス 一般交通量調査 休日調査表 Archived 2013-01-24 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), 2000; page 6. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- 八丈島 II Archived 2018-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- 再評価結果(平成18年度事業継続箇所 一般都道神湊八重根港線(大 Archived 2013-02-02 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Anika Burgess, "Japan’s Abandoned Hotels Are Being Reclaimed by Nature Archived 2018-01-28 at the Wayback Machine", Atlas Obscura, 6 September 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- 大賀郷 9 八丈島歴史民俗資料館 [Okago: 9 Hachijō-jima History and Folk Museum] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Hachijo Island". JapanVisitor.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Hachijojima: Island bliss not far from home". Tokyo Weekender. 17 June 2005. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Noorbakhsh, Sarah (3 July 2008). "Tokyo's Secret Scuba". Japan Inc. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Hachijo-town" (PDF). Hachijo Island Geothermal Energy Museum. 30 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Kendall, Philip (17 September 2012). "Just 45 minutes from Haneda Airport: 6 things that make Hachijo-jima a hidden gem". Japan Today. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- はちじょう 2015 [Hachijō 2015] (PDF) (in Japanese). Hachijō. 2015. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- あしたば [Ashitaba] (in Japanese). Hachijō. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

Further reading

- Tsune Sugimura; Shigeo Kasai. Hachijo: Isle of Exile. New York: Weatherhill, 1973. ISBN 978-0-8348-0081-6

- Teikoku's Complete Atlas of Japan. Tokyo: Teikoku-Shoin, 1990. ISBN 4-8071-0004-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hachijojima. |

- Hachijojima – Japan Meteorological Agency (in Japanese)

- "Hachijojima: National catalogue of the active volcanoes in Japan" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency.

- Hachijo Jima Volcano Group – Geological Survey of Japan

- Hachijojima: Global Volcanism Program – Smithsonian Institution