HMS Inflexible (1876)

HMS Inflexible was a Victorian ironclad battleship carrying her main armament in centrally placed turrets. The ship was constructed in the 1870s for the Royal Navy to oppose the perceived growing threat from the Italian Regia Marina in the Mediterranean.

.jpg) HMS Inflexible with the pole masts fitted in 1885,[1] replacing the original full sailing rig | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by: | Ajax class |

| History | |

| Builder: | Portsmouth Dockyard |

| Cost: | £812,000 |

| Laid down: | 24 February 1874 |

| Launched: | 27 April 1876 |

| Commissioned: | 5 July 1881 |

| Fate: | Scrapped 1903 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 75 ft (23 m) |

| Draught: | 26.3 ft (8.0 m) |

| Propulsion: | 12 coal-fired boilers, two single-expansion Elder and Co. steam engines, 2 twin-bladed 20 ft (6.1 m) diameter screws |

| Speed: | 14.73 knots (27 km/h) @ 6,500 hp (4.8 MW) |

| Range: | "Cross-Atlantic at economical speed" |

| Complement: | 440–470 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

The Italian Navy had started constructing a pair of battleships, Caio Duilio and Enrico Dandolo, equipped with four Armstrong 17.7-inch (450 mm) guns weighing 100 tons each. These were superior to the armament of any ship in the British Mediterranean Squadron, and Inflexible was designed as a counter to them.

Inflexible mounted larger guns than those of any previous British warship and had the thickest armour ever to be fitted to a Royal Navy ship. Controversially, she was designed so that if her un-armoured ends should be seriously damaged in action and become water-logged, the buoyancy of the armoured centre section of the ship would keep her afloat and upright.

The ship was the first major warship to depend in part for the protection of her buoyancy on a horizontal armoured deck below the water-line rather than armoured sides along the waterline.

Design

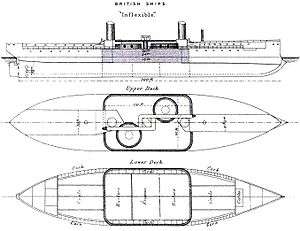

The original concept was based upon an outline design similar to that for HMS Dreadnought, but with improved armament. The ship was conceptually constructed from three components, several outline studies being produced by Nathaniel Barnaby.

A heavily armoured citadel 75 feet (23 m) wide and 110 feet (34 m) long was located amidships, which would keep the ship afloat and stable regardless of what happened to the ends. This citadel contained the main guns, the boilers and the engines. The ends were unarmoured, but with a 3-inch-thick (76 mm) armoured deck 6–8 ft below the waterline to limit damage to the underwater section to keep them buoyant. Coal bunkers were located over the armoured deck and surrounded by 4-foot-wide (1.2 m) compartments filled with cork. The ship had bunker capacity for 400 tons of coal below the deck for use during combat, when the above-deck bunkers would be inaccessible and possibly flooded. The structure above the armoured deck also contained a large number of watertight compartments to further preserve buoyancy. There was also light superstructure to provide crew accommodation, and freeboard in rough weather, although anticipated to be seriously damaged in any major engagement.

Barnaby wanted a ship both broader than existing designs to mimimise rolling and as short as possible to reduce its size as a target. Making a ship broader compared to its length was known to reduce its speed, so the innovative technique of water tank tests on models, pioneered by William Froude, was used to finalise a design. This was ten feet wider than Duillo and twenty-one feet shorter, the smallest ever ratio of length to breadth in a metal first class warship.[2]

Once the outline design was agreed, the detailed architectural design was done by William White[3] and she was laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard on 24 February 1874.

Controversy

Inflexible was launched 27 April 1876. Later that year the MP Edward Reed, formerly Director of Naval Construction, visited the Italian ships and subsequently questioned their stability if the unarmoured ends were flooded.

As Inflexible was of similar design, he raised grave concerns about it too. When he failed to persuade the Admiralty, in June 1877 he publicised his charges in The Times. An editorial in the same edition, 18 June, said "it is said that the unarmoured ends are, in fact, the corks on which she floats, that she cannot swim without them, and it would appear that if she lost one she would capsize".[4]

Further exchanges followed until in July, construction was halted on Inflexible (and two other smaller ships, HMS Ajax and HMS Agamemnon) whilst a hastily convened committee examined the design. In their report published in December 1877, they concluded that it would be hard for gunfire to completely flood the unarmoured but heavily compartmentalised and partially cork-filled ends. However, if this was managed then the ship would just be stable, capsizing at about 35 degrees heel.[4]

Work restarted on the ship in December 1877, and the ship was commissioned 5 July 1881, under Captain John Fisher, although she was not completed until 18 October. Her eventual cost was £812,000.[4]

Main armament

Main guns

To counter the perceived threat from the Italians, Inflexible was to be equipped with four of the largest guns available, weighing 60 tons each. In October 1874 it was decided to modify the design of Inflexible to use an even bigger gun which Armstrongs was producing, a 16-inch (406 mm) gun weighing 81 tons. The Italians responded by changing their design to take even larger 100-ton 17.7-inch (450 mm) Armstrongs guns.[4] As these could not be fitted to Inflexible, four examples were ordered by the British Government, two each for the coastal defences around Gibraltar and Malta respectively. Two of these guns still exist, at Fort Rinnella on Malta and at the Napier of Magdala Battery on Gibraltar.

The four 81-ton muzzle-loading rifles were mounted in two 33-foot-10-inch-diameter (10.31 m) turrets mounted en echelon, with the forward turret mounted on the port side of the ship and the after turret on the starboard side. The superstructure both fore and aft was very narrow to allow one gun in each turret to fire axially, i.e. directly forward or directly aft. In practice, as in previous ships, it was found that axial fire led to so much blast damage to the ship's superstructure that it was impractical. However, the en-echelon arrangement also meant that at least three guns could fire on bearings close to fore and aft. All four guns could be fired broadside.

The en-echelon configuration was retained for the two ships of the Colossus class, but subsequently abandoned in the Royal Navy in favour of centreline mounts at either end of the ship. The en-echelon configuration did not reappear in Royal Navy capital ships until HMS Neptune launched in 1909.

Each turret weighed 750 tons and was protected by an outer layer of 9 inches (230 mm) of compound armour, an inner layer of 7-inch-thick (180 mm) wrought iron, with a total of 18 inches (460 mm) of teak backing.[5] The turrets were rotated hydraulically, taking around a minute to perform a complete rotation.

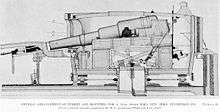

Inflexible's guns were muzzle loaded, and because of their length could not be reloaded from inside the turrets. Consequently reloading was done using hydraulic rams fitted outside the two turrets underneath an armoured glacis. To reload the guns, the turret was rotated to align the guns with the rams, and the guns depressed so that the rams could push the gunpowder charge and 1,684-pound shell into it. The rams had to be extended twice: First, to extinguish any burning material remaining inside the gun using a sponge and water jet fixed to the end of the ram, and then again after charge, shell and wadding had been placed on a loading tray in front of it to be driven into the gun. The shell had a copper disk at its base which engaged with rifled grooves cut into the barrel to spin the shell, rather than zinc studs used on earlier designs. Tests showed that the normal full charge of 450 pounds of brown prismatic gunpowder would produce a muzzle velocity of 1,590 feet per second (480 m/s), which could penetrate 23 inches (580 mm) of wrought iron armour at 1,000 yards (910 m). The muzzle loading took between 2.5 and four minutes.[5]

Ram

She was also equipped with a ram – ramming was considered a practical means of sinking an enemy battleship at that time. The Italian Re d'Italia had been rammed and sunk by the Austrian flagship, Ferdinand Max, at the Battle of Lissa in 1866. This had started a vogue for ramming (which persisted until the 1890s), and many naval experts even believed this was the most effective weapon a ship could have. For example Gerard Noel won the 1874 Royal United Services Institute essay contest with an article that asserted that "[i]n a general action I do not hold that the guns will be the principal weapon".[6]

This was less surprising than it might seem to modern eyes, because it was expected that naval battles would be fought at a range of only a couple of thousand metres. The advent of steam power meant that ships were no longer restricted in manoeuvring by wind direction and had led to a belief that it would be possible to steer into enemy ships. Rams turned out to be a handicap in retrospect, as several warships were accidentally sunk by them – for example HMS Vanguard by HMS Iron Duke in 1875, and HMS Victoria by HMS Camperdown in 1893. Whilst this showed the considerable potency of a ram, it also demonstrated the inadequate manoeuvring characteristics of many of the ships equipped with them. The ram was designed to be removable to avoid damage during accidental collisions, but although other ships customarily carried theirs detached, Inflexible seems to have kept hers in place. The ram was a solid iron forging supported by an extension of the 3-inch (76 mm) armoured deck which turned downwards behind it.[7]

Torpedoes

The ship was fitted with two underwater torpedo tubes. These were cast-iron cylinders attached to a swivel joint in the hull, one on each bow. Inside the ship the opposite end was attached to a graduated scale for targeting. There was a watertight door at either end of the tube. The 14-inch (360 mm) torpedoes were loaded inside a brass cylinder which slid into the iron casting. To fire the torpedo, the outer door was opened and a 10-foot (3.0 m) guide was extended which helped the torpedo clear the currents around the ship. A piston in the brass cylinder forced out the torpedo when it was to be fired, and at the same time its own compressed air motor was started.[7]

Protection

The central citadel in particular was exceptionally heavily armoured. At the waterline, the armour consisted of a 4-foot-wide (1.2 m) layer of 12-inch-thick (300 mm) armour plate backed by 11 inches (280 mm) of teak. Behind this was another 12-inch-thick (300 mm) armour plate backed by 6 inches (150 mm) of teak. Finally on the inside of this were two 5⁄8-inch-thick (16 mm) layers of shell plating. This 41-inch-thick (1,000 mm) layer of protection weighed 1,100 pounds per square foot. 24 inches of armour was considered almost completely proof against any contemporary gun and is still the thickest armour which has ever been used on a battleship.

The armour was reduced to 20 inches (510 mm) thick above the waterline, with a 12-inch-thick (300 mm) outer plate and an 8-inch-thick (200 mm) inner one, with the thickness of teak increased to 21 inches (530 mm) to maintain the same overall thickness of protection. Below the waterline, again there was a 12-inch (300 mm) outer plate, but with a 4-inch-thick (100 mm) inner plate, with 25 inches (640 mm) of teak backing in total to maintain the overall thickness of protection at 41 inches.[5]

Outside the citadel, above the 3-inch-thick (76 mm) armoured deck were a large number of small watertight compartments used to hold coal and stores. Between them and the hull were 4-foot-thick (1.2 m) compartments filled with cork and containing a 2-foot-high (0.61 m) coffer dam. The dam was filled with oakum and canvas which had been shown to help reduce the size of the hole made by a projectile passing through the coffer dam. All of these materials were treated with calcium chloride to try to reduce their flammability. Experiments were carried out with HMS Nettle firing 64-pounder shells into full scale replicas of the cork compartments and coffer dams.

Propulsion

_port_side_view.jpg)

_at_Portsmouth.jpg)

With a slenderness ratio of 4.6:1 Inflexible was a stable gun platform. Work by the hydrodynamicist William Froude had demonstrated that such a short length for the ship's width would not require excessive installed power at the design speed of 14.75 knots (27.32 km/h). However, the same proportions were adopted in the similar but smaller HMS Ajax and HMS Agamemnon, but resulted in a serious lack of directional stability in those ships.

The ship had two compound steam engines manufactured by John Elder and company. Each had one high-pressure and two low-pressure cylinders connected to a crankshaft. The connecting rods were 9 inches (230 mm) in diameter attached to 17.5-inch-diameter (440 mm) bearings on the crankshaft. A hollow steel shaft drove each of the two screws at a maximum 75 rpm. There were two boiler rooms, one each end of the engine room. Each contained two 17-foot (5.2 m) and two 9-foot (2.7 m) boilers operating at 61 psi. Similar high pressure systems had been used on HMS Alexandra launched in 1875 and Temeraire in 1876, but they were a recent innovation and more economical than the previous low pressure engines. Gangs of stokers were continuously bringing coal from the bunkers to feed the fires. The ship had a further 39 smaller engines for various purposes including bilge pumps capable of shifting 300 tons of water per hour, pumps for cooling water through the steam condensers, fans to draw air through the ship through a system of ventilation ducts, steering gear, hydraulic pumps for the guns, air compressors, winches and for generating electricity. The engine room was noisy, wet, greasy, oily and steamy. It would be a normal occurrence for engines to leak steam and for bearings to run hot so that they had to be hosed down to keep them operating. All the essential equipment was contained within the armoured citadel.[8]

Although she was propelled principally by steam, she was equipped with a pair of masts and yards, so that 18,500 square feet (1,720 m2) of sail could be deployed. This was to help exercise and train the crew, especially as such an area of sail (less than 2 square feet (0.19 m2) per ton) would hardly move the ship. As Jackie Fisher wrote: "The sails had so much effect upon her in a gale of wind as a fly would have on a Hippopotamus in producing any movement."[9]

The masts and sails were removed after four years in service,[3] and replaced by simple pole masts for carrying signal flags and circular fighting tops, platforms carrying quick firing guns.

Innovations

She was also the first Royal Navy ship to be completely lit by electricity, and the first to have underwater torpedo tubes. The electrical installation provided 800 volts DC to power arc lamps in the engine and boiler rooms and Swan incandescent bulbs in other parts of the ship. The circuitry was complicated because the lighting consisted of sets of 18 Swan lamps and an arc lamp arranged in series. Each incandescent bulb was fitted with an automatic mechanism to switch in a resistor to maintain continuity should it fail, so that the set of 19 lights would not be extinguished if one failed. The arrangement also led to the first fatal electrocution on a Royal Navy ship, in 1882, after which the Navy adopted an 80 volt standard for its ships.[3]

The ship was equipped with many other novelties, including water tanks to dampen the roll, which turned out to be useless. Much of the ship was without natural illumination, and Fisher had different deck levels painted in contrasting colours to make it easier for crew members to find their way around the ship.[10]

Service history

On completion the ship was sent to join the Mediterranean squadron. She took part in the bombardment of Alexandria on 11 July 1882 during the Urabi Revolt, firing 88 shells[10] and was struck herself twice; one 10-inch (254mm) shell killed the ship's carpenter, mortally wounded an officer directing the fire of a 20-pounder breech-loader, and injured a seaman. The blast from Inflexible's own 16-inch (406 mm) guns did considerable damage to upperworks and boats. She was at this point under command of Captain John Arbuthnot Fisher.[11]

She was refitted in Portsmouth in 1885, when the full sailing rig was removed. She was in the Fleet Reserve until 1890, except for brief service in the 1887 review and the manoeuvres of 1889 and 1890. She was re-commissioned for the Mediterranean Fleet from 1890 to 1893, serving thereafter as Portsmouth guard ship until 1897. From there she went to Fleet Reserve, and in April 1902 to Dockyard Reserve,[12] until sold at Chatham in 1903 for scrap.

References

- Notes

- David K. Brown (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought – Warship development 1860–1905. Chatham Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Padfield p.84

- David K. Brown (1983). A Century of Naval Construction – The History of the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors 1883–1983. Conway Maritime Press. pp. 45–49. ISBN 0-85177-282-X.

- John Beeler (1991). Birth of the Battleship – British capital ship design 1870 – 1881. Chatham Publishing. pp. 122–137. ISBN 1-86176-167-8.

- David K. Brown (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought – Warship development 1860–1905. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- John Beeler (1991). Birth of the Battleship – British capital ship design 1870 – 1881. Chatham Publishing. pp. 105–107. ISBN 1-86176-167-8.

- Padfield p. 86

- Padfield p. 86-87

- Wright, William (2009). A Tidy Little War: The British Invasion of Egypt 1882. Stroud: Spellmount. p. 90. ISBN 9780752450902.

- Robert K. Massie (1992). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the coming of the Great War. Random House. pp. 420–421. ISBN 0-224-03260-7.

- Famous Fighters of the Fleet, Edward Fraser, 1904, p.304

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36751). London. 25 April 1902. p. 8.

- Bibliography

- Oscar Parkes British Battleships ISBN 0-85052-604-3

- Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships ISBN 0-85177-133-5

- Peter Padfield (1972). The battleship era. London: The military book company.

External links