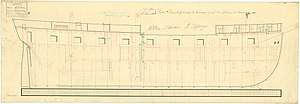

HMS Conway (1814)

HMS Conway was a Royal Navy sixth-rate post ship launched in 1814 as the lead ship of her class. The Royal Navy sold her in 1825 and she became the merchantman Toward Castle, and then a whaler. She was lost in 1838 off Baja California while well into her third whaling voyage.

Conway | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Conway |

| Namesake: | Conwy |

| Ordered: | 18 January 1813 |

| Builder: | John Pelham, Frindsbury |

| Laid down: | May 1813 |

| Launched: | 10 March 1814 |

| Fate: | Sold 1825 |

| Name: | Toward Castle |

| Namesake: | Castle Toward |

| Owner: |

|

| Acquired: | in 1825 by purchase |

| Fate: | Wrecked 1838 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Conway-class sixth-rate post ship |

| Tons burthen: | 4,511, or 45125⁄94[1], or 45148⁄94,[2] or 452 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 30 ft 9 in (9.4 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 9 ft 1 in (2.8 m) |

| Sail plan: | Schooner |

| Complement: | 50 |

| Armament: |

|

Royal Navy

Captain John Tancock commissioned Conway on 1 October 1814 and in 1815 sailed her for the West Indies.[2]

On 26 June 1815 Panther, Gegollas, master, came into Plymouth. Conway, Musquito, Acteon, Tay, and Prometheus had detained Panther as Panther was sailing from Martinique to Dunkirk.[3]

On 22 September 1816 Tancock left Conway to join HMS Iphigenia. His replacement was Captain John Reynolds.[2] Captain William Hill was promoted to post captain on 12 December 1816 and replaced Reynolds.[4]

In 4 July 1817 Captain Edward Barnard replaced Hill,[2] on the East Indies station. Conway was employed protecting British trade in the Persian Gulf and in suppressing the slave trade around Île de France.[5]

On 21 October 1819 Conway was at the Cape of Good Hope. A midshipman and four sailors drowned when their boat swamped while coming alongside Feniscowles, which had been driven ashore and wrecked at Green Point. All on board were rescued. She had been on a voyage from Bengal, India to Mauritius and Liverpool, Lancashire.[6] A later report stated that the second master and two men from Conway had drowned in going to Fenniscowles's assistance.[7]

Conway arrived at Plymouth from the East India station in late December.[7] She sailed on to Portsmouth where she was paid off on 20 January 1820.[5]

Between March and July 1820 Conway underwent refitting for sea duty. She was recommissioned in May under Captain Basil Hall, who sailed for South America on 10 August. She stopped at Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, and the River Plate.[8][Note 1]

On 20 August 1820 Conway sailed from England for the South American station and touched at Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro and the River Plate. Commodore Sir Thomas Hardy, conmmander-in-chief of the South America Station, then ordered Hall to sail to Valparaiso. Conway arrived at Valparaiso at Christmas.[8]

On 22 January 1821 HMS Owen Glendower, Captain Robert Cavendish Spencer, arrived at Valparaiso. Conway then sailed to Callao, arriving there on 31 January.[8]

At the time Lord Cochrane, commander of the insurgent Chilean Navy in the fight for Chile's independence form Spain, was blockading the Spanish-held ports. On 18 February, Captain Hall was at Lima visiting the Viceroy, General de la Serna, and his immediate predecessor, the deposed General Pezuela. In Hall's absence, when two officers from Conway came on shore at Callao, the Peruvian authorities arrested them on the suspicion that the officers were spies for Cochrane. Hall eventually succeeded in getting his officers released.[8]

Conway sailed from Callao on 23 February and on the 24th Hall met with Cochrane on Cochrane's flagship San Martin. Conway sailed on to Valparaiso on the 28th, arriving there on 18 March. She sailed on to Santiago for Hall to meet with Hardy, but then returned to Valparaiso where she remained between 5 April and 26 May. While she was there, her officers made surveys. They also observed a comet that remained in sight between 1 April and 8 June; the data they gathered helped Dr. Brinkley, of Dublin, compute its orbit and publish the results in 1822.[8]

On 26 May Conway sailed along the coast, stopping at Arica on 7 June and Ylo, both of which were almost uninhabited. Between 13 and 20 June Conway was at Mollendo. There Hall discovered that the locals used rafts made of inflated seal skins to cross a surf that would have overturned Conway's boats.[8]

Conway returned to Callao on 24 June and on 25 June Hall met with General San Martin, who was aboard a schooner in Callao roads. On the 5 July the Spanish Viceroy announced that he would abandon Lima; San Martin entered Lima on 12 July and declared Peruvian independence on 28 July.[8]

Hall and Conway then visited Concepción and Arauco, Chile. Arauco had been the base for the pirate Vicente Benavides, who had recently fled, taking with him American and British sailors that he had captured when he captured their vessels.[8][Note 2] Conway then returned to Valparaiso.[8]

On 14 November Conway left Valparaiso to visit ports between there and Lima to assist and protect British interests. she stopped at Coquimbo and Copiapó where one of her midshipmen surveyed the harbour. She stayed at Callao from 9 to 17 December. She then sailed 4,600 miles (7,400 km) from Mocha Island north to San Blas, Nayarit. she arrived at San Blas on 28 March 1822, having stopped at Payta, Guayaquil, the Galápagos Islands, Panama City, and Acapulco.[8]

On 26 April the merchants in San Blas received the authorization of the Mexican Government, conveyed via the state capital of Guadalajara, to send specie to England to pay for goods to be brought back to Mexico. On 6 May Conway took on board more than half a million dollars.[8][Note 3]

Lloyd's List reported 27 September 1822 that a letter from San Blas had stated that Conway would sail for England on 1 June, carrying specie.[11] Conway sailed on 15 June. She then sailed nearly 8,000 miles (13,000 km) to Rio de Janeiro via Cape Horn. Conway arrived at Rio on 12 September. She arrived at England and was paid off at Chatham in the spring of 1823.[8]

Disposal

Conway was laid up at Chatham in 1823.[2] The "Principal Officers and Commissioners of His Majesty's Navy" first offered "Conway, of 26 guns and 452 tons", lying at Chatham, for sale on 27 January 1825.[12] Apparently either she did not sell or the sale fell through and they offered her again on 13 October. Mr. Edward Cohen purchased her on that day for £2,210.[2]

Toward Castle

In 1826 Toward Castle appeared in Lloyd's Register and the Register of Shipping. Both showed her master as Jeffrey or Jeffrys, her owner as Smith, and her trade as London–New South Wales. However, Lloyd's showed her build year as 1808 and the Register as 1810. In much later volumes Lloyd's gave the build year as 1813. Lloyd's Register listed Toward Castle as sailing to New South Wales, having sailed on 17 August 1825.[13]

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser published the manifest of the "Cargo of the Ship Toward Castle, Robert Jeffery, Master, from London and Hobart Town, Van Diemen's Land, to Sydney, New South Wales". The cargo included 300 sheep, rum, wine, merchandise, four carronades, and much else besides.[14]

Whaling voyage #1 (1828–1831)

Captain William Darby Brind sailed from England in 1828, bound for New Zealand. Toward Castle was reported to have been at the Bay of Islands on 9 October, not yet having caught anything. On 25 September 1829 she was again there, with 200 tons of whale oil. In November she was at Tongatapu with 1,650 barrels. She returned to England on 14 July 1831 with 600 casks and 16 tanks of whale oil.[15]

Whaling voyage #2 (1828–1831)

Captain Brind sailed from England on 11 October 1831, again bound for New Zealand. Toward Castle sailed via the Cape of Good Hope and Tonga. On 4 March 1833 she was at the Bay of Islands with 1,500 barrels. She was reported at various times as being at Tonga or the Bay. On 17 November 1833 she was at Oahu. She returned to England via St Helena, arriving on 9 May 1835 with 2,300 barrels of oil.[15]

Fate

Captain Thomas Emmens (or Emmett, or Howarth, or Bennett), sailed from England on 6 October 1835 on Toward Castle's third whaling voyage.[15] Toward Castle, Captain Emmett, was at Monterey, California, in November 1837.

Toward Castle struck a shoal about 50 miles (80 km) north of Cedros Island 28°11′N 115°13′W off Baja California, on 7 January 1838. The crew took to the boats. Captain Emmens, his mate, and five men reached the mission at Todos los Santos, more than 500 miles (800 km) away. From there they went overland some 50 miles to La Paz. Dorotea carried them from there across the Gulf of California to Mazatlán. Samuel Talbot, the United States Consul at Mazatlán, arranged for two American crew members to be repatriated aboard the American schooner Boxer. Captain Emmens, his mate, and the other three crew members shipped aboard the English bark Vesper. As of 7 February there had been no news at Mazatlán of the fate of the remainder of Toward Castle's 30 (or 31) man crew. Talbot thought that they had been lost.[16]

Other reports stated that nine men,[15] or 16, had survived, out of a crew of 31.[17][18] Her cargo of 1,800 barrels of oil were lost. The cause of the wreck was that the location of the island as laid out in her English charts was wrong.[15]

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

- Marshall copied much of his biography of Hall from Hall's book.[9]

- Benavides's men had captured, possibly amongst other vessels, Perseverance in March 1821 and Hersilia in May. Benavides was captured, hanged, and his body mutilated, in February 1822.

- The Navy permitted captains returning to Britain to carry "freight" in the form of remittances. The captains earned a commission of one percent of the value, half of which they kept and half of which went to the Greenwich Hospital (London); unlike in the case of prizes, the crew did not share in the proceeds.[10]

Citations

- Hackman (2001), p. 318.

- Winfield (2008), p. 240.

- Lloyd's List №4984.

- Marshall (1830), Supple. Part 4, p.118.

- Gentleman's Magazine (December 1863), pp.805-6.

- "Ship News." Times [London, England 22 December 1819: 4. The Times Digital Archive.]

- "Ship News." Times [London, England 28 Dec. 1819: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 July 2018.]

- Marshall (1830), Supple., Part 4, pp.164-184.

- Hall (1824).

- Vale (2001), p. 23.

- Lloyd's List №5737.

- "No. 18097". The London Gazette. 8 January 1825. p. 44.

- Lloyd's Register "Ships Trading to Van Diemen's Land and New South Wales".

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 March 1826, p.3.

- British Southern Whale Fishery: Voyages – Toward Castle.

- "Ship News." Times [London, England 28 May 1838: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 July 2018.]

- "Ship News". The Standard (4346). London. 26 May 1838.

- "Shipping Intelligence". The Morning Chronicle (21384). London. 28 May 1838.

References

- Hackman, Rowan (2001). Ships of the East India Company. Gravesend, Kent: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-96-7.

- Hall, Basil (1824). Extracts from a Journal written on the Coasts of Chili, Peru, and Mexico, in the years 1820, 1821, 1822. Edinburgh: Constable.

- Marshall, John (1823–1835). Royal naval biography, or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea officers at the commencement of the present year 1823, or who have since been promoted ... London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

- Vale, Brian (2001). A frigate of King George: life and duty on a British man-of-war 1807-1829. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

External links