Grisaille

Grisaille (/ɡrɪˈzaɪ/ or /ɡrɪˈzeɪl/; French: gris [ɡʁizaj] 'grey') is a painting executed entirely in shades of grey or of another neutral greyish colour.[1] It is particularly used in large decorative schemes in imitation of sculpture. Many grisailles include a slightly wider colour range, like the Andrea del Sarto fresco illustrated. Paintings executed in brown are referred to as brunaille, and paintings executed in green are called verdaille.[2]

A grisaille may be executed for its own sake, as underpainting for an oil painting (in preparation for glazing layers of colour over it), or as a model for an engraver to work from. "Rubens and his school sometimes use monochrome techniques in sketching compositions for engravers."[3] Full colouring of a subject makes many more demands of an artist, and working in grisaille was often chosen as being quicker and cheaper, although the effect was sometimes deliberately chosen for aesthetic reasons. Grisaille paintings resemble the drawings, normally in monochrome, that artists from the Renaissance on were trained to produce; like drawings they can also betray the hand of a less talented assistant more easily than a fully coloured painting.

History

Giotto used grisaille in the lower registers of his frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (c. 1304) and Robert Campin, Jan van Eyck and their successors painted grisaille figures on the outsides of the wings of triptychs, including the Ghent Altarpiece. Originally these were the sides on display for most of the time, as the doors were normally kept closed except on feast days or at the (paid) request of tourists. However today these images are often invisible in museums when the tryptych is displayed open and flat against a wall. In these cases imitation of sculpture was intended; sculpture was still more expensive than a painting - even one by an acknowledged master.

Limners had often produced illuminated manuscripts in pen and wash with a very limited colour-range, and many artists such as Jean Pucelle ( active c. 1320-1350) and Matthew Paris specialised in such work, which had been especially common in England since Anglo-Saxon times. Renaissance artists such as Mantegna and Polidoro da Caravaggio often used grisaille as a classicising effect, either in imitation of the effect of a classical sculptured relief, or of Roman painting.

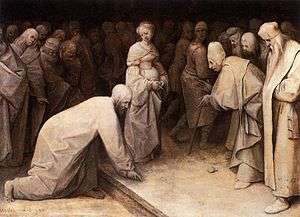

In the Low Countries a continuous tradition of grisaille paintings can be traced from Early Netherlandish painting to Martin Heemskerck (1498-1574), Pieter Brueghel the Elder (Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, 1565) and Hendrik Goltzius, and through the copious output of Adriaen van de Venne, to the circle of Rembrandt, and Jan van Goyen.

The ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel have portions of the design in grisaille, as does the lower part of the great staircase decoration by Antonio Verrio (c. 1636 – 1707) at Hampton Court.

Modern examples

Grisaille, while less widespread in the 20th Century, continues as an artistic technique. Pablo Picasso's painting Guernica (1937) is one example.

Hugo Bastidas (1955- ), a contemporary American painter, has become known for black-and-white paintings that imitate the effect of grisaille and often resemble black-and-white photographs.[4] Bastidas' paintings frequently reference architecture, water, vegetation and art history, and reflect his concern about the human condition, globalization, and their effect on the Earth's well-being.[5] After returning to New York from a Fulbright Fellowship in his native Ecuador in the early 1990s, Bastidas began using a restricted color-palette of black and white.[4] His medium- and large-scale paintings allude to black-and-white photography, and feature contrasting zones of high and low detail.[4][6] By making thousands of marks with a size No. 1 hog's bristle brush on linen primed with rabbit-skin glue, Bastidas achieves a high level of image definition.[4][7] He also works in digital photography, which informs his subject matter without rendering a photo-realistic effect.[8]

Academic study

With the 20th century's emphasis on direct (alla prima) painting, the grisaille technique lost favour with artists of the period. This historic method is still incorporated into the curriculum of some private ateliers.[9]

In enamel and stained glass

The term is also applied to monochrome painting in other media such as enamels, where an effect similar to a relief in silver may be intended. It is common in stained glass, where the need for sections in different colours was thereby greatly reduced. Portions of a window may be done in grisaille – using, for example, silver stain or vitreous paint – while other sections are done in coloured glass.

Gallery

Molded Tile, mid-19th century Iran. Brooklyn Museum

Molded Tile, mid-19th century Iran. Brooklyn Museum Master of Frankfurt, Saint Odile and Saint Cecilia, ca. 1503–1506, oil on panel, Historical museum, Frankfurt.

Master of Frankfurt, Saint Odile and Saint Cecilia, ca. 1503–1506, oil on panel, Historical museum, Frankfurt. Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, Infidelity

Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, Infidelity Andrea del Castagno, monument to Niccolò da Tolentino

Andrea del Castagno, monument to Niccolò da Tolentino

Triptych shutter outside panel by Hieronymus Bosch

Triptych shutter outside panel by Hieronymus Bosch Frans Francken II by Anthony van Dyck, one of a series of studies for portrait prints

Frans Francken II by Anthony van Dyck, one of a series of studies for portrait prints

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto_20-May-2007.jpg) Italian palace staircase, 18th century

Italian palace staircase, 18th century Student copy in grisaille after Jacques-Louis David[10]

Student copy in grisaille after Jacques-Louis David[10] Painted Fire Screen by Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis. Pair of figures painted on the right side are in the Grisaille style. The Walters Art Museum.

Painted Fire Screen by Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis. Pair of figures painted on the right side are in the Grisaille style. The Walters Art Museum. Window of St. Peter: Stained glass (white glass, grisaille and silver sulfide) and lead, France, ca. 1500–1510

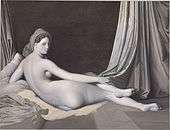

Window of St. Peter: Stained glass (white glass, grisaille and silver sulfide) and lead, France, ca. 1500–1510 Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and his workshop, Odalisque in Grisaille

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and his workshop, Odalisque in Grisaille

See also

- Brunaille

- Sepia tone (photography)

- Zorn palette

References and notes

- References

- Notes

- Chilvers, Ian (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art, 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 314

- Christie’s, Sale 1380, Old Master Paintings, lot 49, New York, Christie’s, 17 June 2004.

- Oxford Companion to Art. Ed. Harold Osborne; Clarendon Press. Oxford, 1970.

- Carvalho, Denise (April 2008). "Hugo Bastidas at Nohra Haime". Art in America. p. 169.

- "Hugo Bastidas". Nohra Haime Gallery. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Dawson, Jessica. "Without Hue: A Rainbow of Grays". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Bardier, Laura. "Hugo Bastidas". Arte Al Dia. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "Hugo Bastidas". Mattatuck Museum. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- For example, at The Contemporary Realist Academy, in Memphis, Tennessee, The Ryder Studio in Santa Fe, New Mexico and Ecole Albert Defois in France.

- Mims Studios School of Fine Art

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grisaille. |