Great Bolas

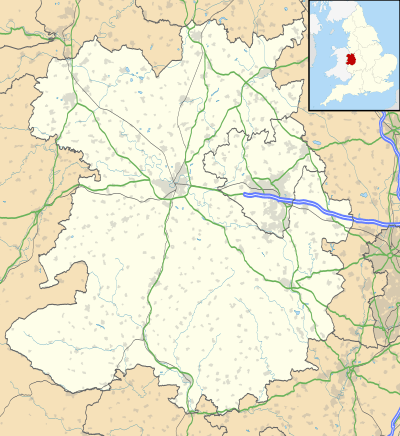

Great Bolas, or Bolas Magna, is a small village in rural Shropshire, England. It is situated north-west of the town of Newport, and about eight miles north of Telford.[1] It is part of the civil parish of Waters Upton. It is situated at the confluence of the Tern and the small River Meese. There is a hamlet called Little Bolas a short distance to the west. Another hamlet called Meeson, south of the River Meese, was formerly a separate township of Great Bolas parish.[2]

| Great Bolas | |

|---|---|

Great Bolas bridge over the River Meese, near the hamlet of Meeson | |

Great Bolas Location within Shropshire | |

| Population | 320 (2001) |

| OS grid reference | SJ648214 |

| Civil parish | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | TELFORD |

| Postcode district | TF6 |

| Dialling code | 01952 |

| Police | West Mercia |

| Fire | Shropshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Etymology

The placename is attested in medieval documents since c.1200 as Boulewas, Bouldwas, Boulwas and similar forms.[3] It is believed to derive from a compound whose second element was the Old English word wæsse (Middle English was), possibly meaning 'a riverside place that is prone to quick flooding'; this element is thought to appear also in the names Alrewas, Broadwas, Buildwas, Hopwas, Rotherwas and Sugwas.[4] The first element has been identified as either a form of Old English *bogel 'little bend',[3] or of Old English bold 'house'.[5]

Boundary and administrative changes

The Domesday Book does not mention Great Bolas, as at that time it was part of the manor of Isombridge, held by Ralph de Mortimer of Earl Roger de Montgomery. It was either him, or his son Earl Hugh who founded the Forestership of Shropshire. The chief forester of Shropshire lived in Great Bolas, and the Foresters of Shropshire were known as the "Foresters of Bolas".[5] Great Bolas was once part of an Ecclesiastical Parish, and later became part of the civil Parish of Waters Upton.[6]

Village amenities

In 1284, Great Bolas was owned by one of the foresters who looked after the Royal Forest of Wrekin, a twice yearly court and gallows were set up making the village important in the surrounding area.[5] In 1881 the village had a rectory, a school, grave yard, a corn mill named Bolas Mill, post office, a pump and two wells along with St John’s Church.[7] By 1901, Manor Farm was built as well as an extra pump.[8] By 1926 a Parish room was added and Bolas House was extended. Bolas Mill is now disused but the building remains standing.[9] In 1971, Manor Farm changed its name to Bolas Manor and the River Meese’s course was also straightened.[10][11]

St. John the Baptist's Church

The village church, dedicated to St. John the Baptist,[2] dates largely from the 17th century, with an 18th-century tower and some 14th century pews.[12] It was built in a mixture of Renaissance and rural Gothic styles.[5] The chancel was built in 1690 and was funded by Mr. John Tourneor, the rector at the time. He died in January 1693–94. After his death a nave and tower were built out of brick with a stone finish. This part of the church was designed by John Willbigg, with a funds – amounting to a total of £331 – raised by church donations. The completed new church was opened on 23 June 1728.[5] Of an earlier church in the same location, dating back to the 13th century, nothing remains except for two stones in the east window.

Henry Cecil, 1st Marquess of Exeter

Great Bolas is known for its association with Henry Cecil, 1st Marquess of Exeter. Henry Cecil found refuge in Thomas Hoggins’s household in June 1789 after fleeing from debt he fell into after his first wife eloped with another man. He said his name was John Jones and remained there for some weeks, this is known as he was witness to a local marriage on 18 July. He and Sarah Hoggins, the daughter of Thomas Hoggins, were married in April 1790, still under the name of John Jones. As Henry Cecil, he was still married, so from the Consistory Court he got a divorce, as well as an Act of Parliament pronouncing him able to remarry. At the St Mildred, Bread Street church in London on 3 October 1791, Sarah Hoggins married Henry Cecil again, under his true name. The name John Jones was still used after the second marriage, as it appears in rate books as well as in Great Bolas Registers at the time. Whilst living in Great Bolas, Henry Cecil bought some land in the village and built Bolas Villa, a small house for him and his family. Henry Cecil succeeded his uncle as the 10th Earl of Exeter after he died in December 1793. His wife Sarah died after giving birth to their fourth child. Henry Cecil died aged 50 in 1804, after marrying again after Sarah Hoggins' death. It was his and Sarah's third child named Brownlow who succeeded as Marquess of Exeter. After Henry Cecil left Great Bolas, he gave Bolas Villa to Creswell Tayleur his godchild, he had the house enlarged and then changed the name to Burghley Villa. Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem The Lord of Burleigh was based on Henry Cecil’s story.[5]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 207 | — |

| 1811 | 229 | +10.6% |

| 1821 | 274 | +19.7% |

| 1831 | 255 | −6.9% |

| 1841 | 288 | +12.9% |

| 1851 | 279 | −3.1% |

| 1861 | 275 | −1.4% |

| 1871 | 316 | +14.9% |

| 1881 | 304 | −3.8% |

| 1891 | 269 | −11.5% |

| 1901 | 255 | −5.2% |

| 1911 | 283 | +11.0% |

| 1921 | 264 | −6.7% |

| 1931 | 273 | +3.4% |

| 1951 | 265 | −2.9% |

| 1961 | 246 | −7.2% |

| 1971 | 213 | −13.4% |

| 2001 | 320 | +50.2% |

Occupational structure

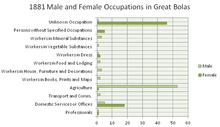

In 1811 out of the 36 families residing in Great Bolas, 34 were "chiefly employed in agriculture", and the remaining two were "chiefly employed in trade, manufacture or handicraft".[13] The 1881 census shows that still the majority of males were employed in the Agriculture sector, while the majority of females worked in either an unknown occupation, or in the sector of domestic services and office employment.[14]

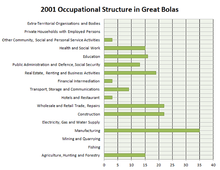

In the 2001 census, only 9% of Great Bolas is employed within the Agriculture, Hunting and Forestry sector. Manufacturing is the sector with the highest proportion of employees, with 20% of the Great Bolas population working within it. Both the construction sector along with the wholesale and retail trade sector have 13% of the population working within each which, so these three industries account for a high proportion of Great Bolas' employment structure.[15] The 1881 census records that there was a very low number of people who were professionals,[14] whereas in the 2001 census just under half the population were in professional, managerial, supervisory, administrative or clerical employment.[16]

Population

The population of Great Bolas has remained relatively stable. The 1801 census recorded the population as 207,[17] This gradually rose (with the exception of a few years where the population dropped) until it peaked at 316 in 1871.[18][19] From here, the population gradually dropped[20] through to 1971 where the census recorded the population as 213.[21][22] From 1971 to 2001, the population had grown to 320.[23]

References

- "Visitor UK". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Great Bolas, GENUKI

- Gelling, Margaret; Foxall, H. D. G. (1990). The place names of Shropshire. 1. English Place-Name Society. p. 51.

- Lincolnshire History and Archaeology: 74. 2000. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Shropshire Parish Registers". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- "Vision of Britain: Unit History and Boundary Changes2". Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- 1881 Ordnance Survey Map, Country Series 1:2500, 1st Edition, OS Grid: SJ62

- 1902 Ordnance Survey Map, Country Series 1:2500, 1st Revision, OS Grid: SJ62

- 1926 Ordnance Survey Map, Country Series 1:2500, 2nd Revision, OS Grid: SJ62

- 1971 Ordnance Survey Map, Country Series 1:2500, OS Grid: SJ62

- "Historical Ordnance Survey Maps". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Raven, M. A Guide to Shropshire, 2005, p.82

- "Online Historical Population Reports – 1811". Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- "Occupational Data for 1881". Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- "2001 Neighbourhood Statistics: Industry of Employment". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "2001 Neighbourhood Statistics: Approximated Social Grade". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- 1851 Census of Great Britain Population Table 2, Table (1) 'Population Abstract'

- 1871 Census of England and Wales, Population Tables, Vol. 1, Table 10 Inhabited Houses, Families or Separate Hoccupiers, and Population of Civil Parishes and Townships

- "Histpop: 1871 Census Data". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Vision of Britain: Historical Populations". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Mimas Census Data – 1971 Population". Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- 1971 Census of England and Wales, Population Data

- "2001 Neighbourhood Statistics: Population". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Bolas. |