Sandford Fleming

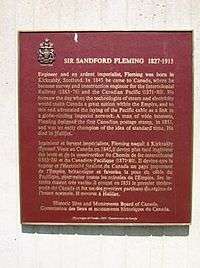

Sir Sandford Fleming KCMG (January 7, 1827 – July 22, 1915) was a Scottish Canadian engineer and inventor. Born and raised in Scotland, he emigrated to colonial Canada at the age of 18. He promoted worldwide standard time zones, a prime meridian, and use of the 24-hour clock as key elements to communicating the accurate time, all of which influenced the creation of Coordinated Universal Time.[1] He designed Canada's first postage stamp, left a huge body of surveying and map making, engineered much of the Intercolonial Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway, and was a founding member of the Royal Society of Canada and founder of the Canadian Institute, a science organization in Toronto.

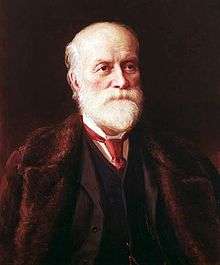

Sir Sandford Fleming | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Sir Sandford Fleming by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster | |

| Born | January 7, 1827 Kirkcaldy, Scotland |

| Died | July 22, 1915 (aged 88) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Occupation | engineer and inventor |

| Known for | Inventing, most notably standard time |

Early life

In 1827, Fleming was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland[2] to Andrew and Elizabeth Fleming. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed as a surveyor and in 1845,[3] at the age of 18, he emigrated with his older brother David to colonial Canada. Their route took them through many cities of the Canadian colonies: Quebec City, Montreal, and Kingston, before settling in Peterborough with their cousins two years later in 1847. He qualified as a surveyor in Canada in 1849.[4]

In 1849 he created the Royal Canadian Institute with several friends, which was formally incorporated on November 4, 1851. Although initially intended as a professional institute for surveyors and engineers it became a more general scientific society. In 1851 he designed the Threepenny Beaver, the first Canadian postage stamp, for the Province of Canada (today's southern portions of Ontario and Quebec). Throughout this time he was fully employed as a surveyor, mostly for the Grand Trunk Railway. His work for them eventually gained him the position as Chief Engineer of the Northern Railway of Canada in 1855, where he advocated the construction of iron bridges instead of wood for safety reasons.

Fleming served in the 10th Battalion Volunteer Rifles of Canada (later known as the Royal Regiment of Canada) and was appointed to the rank of captain on January 1, 1862. He retired from the militia in 1865.

Family

As soon as he arrived in Peterborough, Ontario in 1845, Fleming became friendly with the family of his future wife, the Halls, and was attracted to Ann Jane (Jeanie) Hall. However, it was not until a sleigh accident almost ten years later that the young people’s love for each other was revealed. A year after this incident, in January 1855, Sandford married Ann Jane (Jean) Hall. They were to have nine children of whom two died young. The oldest son, Frank Andrew, accompanied Fleming in his great Western expedition of 1872. A family man, deeply attached to his wife and children, he also welcomed his father Andrew Greig Fleming, Andrew's wife and six of their other children who came to join him in Canada two years after his arrival. The Fleming and Hall families saw each other often.

After the death of his wife Jeanie in 1888, Fleming's niece Miss Elsie Smith, daughter of Alexander and Lily Smith, of Kingussie, Scotland, presided over his household at "Winterholme" 213 Chapel Street, Ottawa, Ontario.[5]

Railway engineer

His time at the Northern Railway was marked by conflict with the architect Frederick William Cumberland, with whom he started the Canadian Institute and who was general manager of the railway until 1855. Starting as assistant engineer in 1852, Fleming replaced Cumberland in 1855 but was in turn ousted by him in 1862. In 1863 he became the chief government surveyor of Nova Scotia charged with the construction of a line from Truro to Pictou. When he would not accept the tenders from contractors that he considered too high, he was asked to bid for the work himself and completed the line by 1867 with both savings for the government and profit for himself.[6]

In 1862 he placed before the government a plan for a transcontinental railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.[7] The first part, between Halifax and Quebec became an important part of the preconditions for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to join the Canadian Federation because of the uncertainties of travel through Maine because of the American Civil War. In 1867 he was appointed engineer-in-chief of the Intercolonial Railway which became a federal project and he continued in this post till 1876. His insistence on building the bridges of iron and stone instead of wood was controversial at the time, but was soon vindicated by their resistance to fire.[8]

By 1871, the strategy of a railway connection was being used to bring British Columbia into federation and Fleming was offered the chief engineer post on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Although he hesitated because of the amount of work he had, in 1872 he set off with a small party to survey the route, particularly through the Rocky Mountains, finding a practicable route through the Yellowhead Pass. One of his companions, George Monro Grant wrote an account of the trip, which became a best-seller.[9] By 1880, with 600 miles completed, a change of government brought a desire for a private company to own the whole project and Fleming was dismissed by Sir Charles Tupper, with a $30,000 payoff.[8][10] It was the hardest blow of Fleming's life, though he obtained a promise of monopoly, later revoked, on his next project, a trans-pacific telegraph cable.[8] Nevertheless, in 1884 he became a director of the Canadian Pacific Railway and was present as the last spike was driven.

Inventor of worldwide standard time

After missing a train while traveling in Ireland in 1876 because a printed schedule listed p.m. instead of a.m., he proposed a single 24-hour clock for the entire world, with the 24 hour divisions (labelled A-Y, excluding J) arbitrarily linked to the Greenwich meridian, which was designated G.[12] At a meeting of the Canadian Institute in Toronto on February 8, 1879, he linked it to the anti-meridian of Greenwich (now 180°). He suggested that standard time zones could be used locally, but they were subordinate to his single world time, which he called Cosmic Time.[13] He continued to promote his system at major international conferences[14] including the International Meridian Conference of 1884. That conference accepted a different version of Universal Time but refused to accept his zones, stating that they were a local issue outside its purview. Nevertheless, by 1929, all major countries in the world had accepted time zones.

Later life

When the railway privatization instituted by Tupper in 1880 forced him out of a job with government, he retired from the world of surveying, and took the position of Chancellor of Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario.[15] He held this position for his last 35 years, where his former Minister George Monro Grant was principal from 1877 until Grant's death in 1902. Not content to leave well enough alone, he tirelessly advocated the construction of a submarine telegraph cable connecting all of the British Empire, the All Red Line, which was completed in 1902.[16]

He also kept up with business ventures, becoming in 1882 one of the founding owners of the Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company in Halifax. He was a member of the North British Society.[17] He also helped found the Western Canada Cement and Coal Company, which spawned the company town of Exshaw, Alberta. In 1910, this business was captured in a hostile take-over by stock manipulators acting under the name Canada Cement Company, which action was said by some to lead to an emotional depression that would contribute to Fleming's death a short time later.[18]

In 1880 he served as the vice president of the Ottawa Horticultural Society.[19] In 1888, he became the first president of the Rideau Curling Club,[20][21] after leaving the Ottawa Curling Club in protest of its temperance policy.[22]

His accomplishments were well known worldwide, and in 1897 he was knighted by Queen Victoria. He was a freemason.[23]

In 1883, while surveying the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway with George Monro Grant, he met Major A. B. Rogers near the summit of Rogers Pass (British Columbia) and co-founded the first "Alpine Club of Canada".[24] That early alpine club was short-lived, but in 1906 the modern Alpine Club of Canada was founded in Winnipeg, and the by then Sir Sandford Fleming became the Club's first Patron and Honorary President.[25]

In his later years he retired to his house in Halifax, later deeding the house and the 95 acres (38 hectares) to the city, now known as Sir Sandford Fleming Park (Dingle Park). He also kept a residence in Ottawa, and was buried there, in the Beechwood Cemetery.

Legacy

Fleming was designated a National Historic Person in 1950, on the advice of the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board.[27] On January 7, 2017, Google celebrated Sandford Fleming's 190th birthday with a Google Doodle.[28]

Things named after Fleming

Geographical features

- The town of Fleming, Saskatchewan (located on the Canadian Pacific Railway) was named in his honour in 1882.[29]

- Mount Sir Sandford, which is the highest mountain in the Sir Sandford Range of the Selkirk Mountains, and the 12th highest peak in British Columbia, is named after him.[30]

- Sandford Island and Fleming Island in Barkley Sound, British Columbia were named after him.[31]

- Sir Sandford Fleming Park, a 38-hectare (94-acre) Canadian urban park in Halifax, also known as “The Dingle” (as shown above under "Later life").

Buildings and institutions

- Fleming Hall was built in his honour at Queen's in 1901, and rebuilt after a fire in 1933. It was the home of the university's Electrical Engineering department.[32]

- In Peterborough, Ontario, Fleming College, a Community College of Applied Arts and Technology bearing his name, was opened in 1967, with additional campuses in Lindsay/Kawartha Lakes, Haliburton, and Cobourg.[33]

- The Sandford Fleming building of the University of Toronto Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering (Sandford Fleming building)[34]

- Sir Sandford Fleming elementary school was built in Vancouver in 1913.[35]

- Sir Sanford Fleming Academy, located in North York, Ontario was built in 1964 and was renamed to John Polanyi Collegiate Institute in 2011.[36]

Postage stamps

Fleming has been honoured on two Canadian postage stamps: one from 1977 features his image and a railroad bridge of Fleming's design;[37] another in 2002 reflects his promotion of the Pacific Cable.[38] In addition, his design of the Three Penny Beaver, the first postage stamp for the Province of Canada (today's southern portions of Ontario and Quebec), has been used on seven stamp issues—in 1851, 1852, 1859, 1951, and 2001.

See also

References

- Creet, Mario (1990). "Sandford Fleming and Universal Time". Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine. 14 (1–2): 66–89. doi:10.7202/800302ar.

- "Life at full speed: Artist, scientist and inventor". sandfordfleming.ca. Canadian Railway Museum. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Life at full speed: The apprentice". sandfordfleming.ca. Canadian Railway Museum. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Life at full speed: Finding a first job". sandfordfleming.ca. Canadian Railway Museum. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 320.

- Grant, W. L. (2005) [2004]. "Fleming, Sandford". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33171. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fleming, Sandford (1862), Suggestions on the Inter-colonial Railway, archived from the original on April 21, 2016, retrieved January 25, 2013

- Creet, Mario, FLEMING, Sir SANDFORD, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, archived from the original on May 19, 2013

- Grant, George Monro (1873), Ocean to Ocean, Toronto : Belford, hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t0tq7358g, archived from the original on March 11, 2016, retrieved January 25, 2013

- Buckner, Phillip (1998). "TUPPER, Sir CHARLES". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XIV (1911–1920) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- Brown, Alan L. (June 2010). "Birthplace of Standard Time Historical Plaque". Toronto's Historical Plaques. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- Bartky, Ian (2007). One Time Fits All: The Campaigns for Global Uniformity. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780804756426.

- Fleming, Sandford (1886). "Time-reckoning for the twentieth century". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (1): 345–366. Reprinted in 1889: Time-reckoning for the twentieth century at the Internet Archive.

- Including Geographical Congress at Venice in 1881, and at a meeting of the Geodetic Association at Rome in 1883 "Popular Science Monthly Volume 29 October 1886". Archived from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2011. , page 799

- "Descriptive records – National Archives of Canada". Archived from the original on August 24, 2013.

- Pacific Cable National Historic Event. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- Macdonald, James S. (1905). Annals, North British Society, Halifax, Nova Scotia : with portraits and biographical notes, 1768-1903. Halifax, N.S: McAlpine. pp. 414.

- The Western Canada Cement and Coal Company, 1910 (CIHM microfilm collection); Journal of Commerce, July 1930

- Premium list of Valley of Ottawa Horticultural Society Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Rideau Curling Club :: Club History".

- "Rideau Curling Club celebrates 125 years in Ottawa | CBC News".

- "The Ottawa Curling Club : Club History".

- Trevor W. McKeown. "A few famous freemasons". Archived from the original on September 12, 2015.

- Putnam, William Lowell (June 1982). "Chapter 8". The Great Glacier and Its House. American Alpine Club. ISBN 978-0930410131.

- Cormie, David (December 3, 2014). "ACC Centennial Plaque Project". Alpine Club of Canada, Manitoba Section. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- Sir Sandford Fleming 1827–1915 Archived January 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, historical marker from OntarioPlaques.com, 2009

- Fleming, Sir Sandford National Historic Person. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cory Toth – Encyclopedia Of Saskatchewan. "The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan – Details". Archived from the original on May 27, 2013.

- "Mount Sir Sandford". BC Geographical Names.>

- Akrigg, G.P.V & Helen (1997). British Columbia Place Names (3rd ed.). University of British Columbia Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-7748-0636-2.

- "Fleming Hall". Queen's Encyclopedia. Queen's University. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Fleming 50th". Fleming College. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Sandford Fleming Building". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "South Vancouver High School – A memory in the community". Heritage Vancouver. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/oise/News/cbc_national_great_teachers_docseries_110829.html

- Canadian Postal Archives Database Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Sandford Fleming stamp, National Library and Archives, no date

- Canadian Postal Archives Database Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Pacific Cable, Fleming, National Library and Archives, no date

- Creet, Mario (1998). "Fleming, Sir Stanford". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XIV (1911–1920) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Regehr, T.D. (July 24, 2015) [February 21, 2008]. "Sir Sandford Fleming". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

Further reading

- Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandford Fleming. |

- Works by Sandford Fleming at Project Gutenberg

- sandfordfleming.ca: Sources

- Works by Sir Sandford Fleming at Faded Page (Canada)

- Heritage Minutes: Sir Sandford Fleming

- Ontario Historical Plaques

- Biography from Sir Sandford Fleming College website

- Reverend Shirra and Sir Sandford Fleming Plaque in Kirkcaldy

- Sir Sandford Fleming circa 1885

- Sir Sandford Fleming in 1903

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, Sir Sandford Fleming

- Fleming, Sandford (1876), "Terrestrial Time", Canadian Institute

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Cook |

Chancellor of Queen's College/Queen's University 1880–1915 |

Succeeded by James Douglas |

| Professional and academic associations | ||

| Preceded by George Lawson |

President of the Royal Society of Canada 1888–1889 |

Succeeded by Raymond Casgrain |