Going-to-the-Sun Road

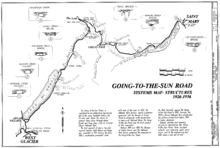

Going-to-the-Sun Road is a scenic mountain road in the Rocky Mountains of the western United States, in Glacier National Park in Montana. The Sun Road, as it is sometimes abbreviated in National Park Service documents, is the only road that traverses the park, crossing the Continental Divide through Logan Pass at an elevation of 6,646 feet (2,026 m), which is the highest point on the road.[3] Construction began in 1921 and was completed in 1932 with formal dedication in the following summer on July 15, 1933.[4][5] The road is the first to have been registered in all of the following categories: National Historic Place,[6] National Historic Landmark[2] and Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.[7] The road is approximately 50 miles (80 km) long and spans the width of the park between the east and west entrance stations.[3] The National Historic Landmark Nomination records a slightly shorter distance of 48.7 miles which is measured from the first main intersection just outside the park's west entrance to Divide Creek in St. Mary on the east side of the park.[3]

Going-to-the-Sun Road | |

Looking east from Logan Pass toward Going-to-the-Sun Mountain (left foreground) | |

Location in Montana  Going-to-the-Sun Road (the United States) | |

| Location | Glacier National Park, Flathead / Glacier counties, Montana, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | West Glacier, Montana |

| Coordinates | 48.695°N 113.817°W |

| Built | 1921-1932; dedicated 1933 |

| Architect | National Park Service; Bureau of Public Roads |

| NRHP reference No. | 83001070 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 16, 1983[1] |

| Designated NHL | February 18, 1997[2] |

The road is one of the most difficult roads in North America to snowplow in the spring. Up to 80 feet (24 m) of snow can lie on top of Logan Pass, and more just east of the pass where the deepest snowfield has long been referred to as the Big Drift. The road takes about ten weeks to plow, even with equipment that can move 4,000 tons of snow in an hour. The snowplow crew can clear as little as 500 feet (150 m) of the road per day. On the east side of the Continental Divide, there are few guardrails due to heavy snows and the resultant late-winter avalanches that have destroyed protective barriers. The road is generally open from early June to mid October, with its late opening on July 13, 2011, marking the record for the latest opening since the inaugural date of July 15, 1933.[4]

The two-lane Going-to-the-Sun Road is quite narrow and winding, with hairpin turns, especially west of Logan Pass. Consequently, vehicle lengths over the highest portions of the roadway are limited to no longer than 21 feet (6.4 m) and no wider than 8 feet (2.4 m) between Avalanche Creek and Rising Sun picnic areas which are located many miles below Logan Pass, on the west and east sides of the pass, respectively. Vehicles over 10 feet (3.0 m) in height may not have sufficient clearance due to rock overhangs when driving west between Logan Pass and the hairpin turn called the Loop.[3]

Prior to the construction of the road, visitors would need to spend several days traveling through the central part of the park, an area which can now be traversed within a few hours, excluding any stops for sightseeing or construction. The speed limits are 45 mph (72 km/h) in the lower elevations and 25 mph (40 km/h) in the steeper and winding alpine sections.[3]

Name

The road is named after Going-to-the-Sun Mountain which dominates the eastbound view beyond Logan Pass. One Native American legend concerns the deity Sour Spirit who came down from the sun to teach the Blackfeet the basics of hunting. While returning to the sun, an image of Sour Spirit was placed on the mountain as an inspiration for the Blackfeet. Another story has suggested that a late-19th-century Euro-American explorer provided the mountain's name and the legend.[3]

Design

Going-to-the-Sun Road is notable as one of the first National Park Service projects specifically intended to accommodate the automobile-borne tourist. The road was first conceived by superintendent George Goodwin in 1917, who became the chief engineer of the Park Service the following year.[8] As chief engineer, the new road became Goodwin's primary project, and construction began in 1921.

As the project proceeded, Goodwin lost influence with National Park Service director Stephen Mather, who favored landscape architect Thomas Chalmers Vint's alternative routing of the upper portion of the road along the Garden Wall escarpment. Vint's alignment reduced both switchbacks and the road's visual impact, at increased cost.[9] With Goodwin's resignation, Vint's proposal became the preferred alignment. The entire project was finally opened from end to end in 1933, at a cost of $2.5 million.[10]

Repairs

A restoration project by the National Park Service and the Federal Highway Administration has been repairing road damage from many avalanches and rock slides over the years.[11] The repairs, which started in the 1980s and continue to the present day when weather permits, include fixing retaining walls, replacing the original pavement with reinforced concrete, and work on tunnels, bridges, culverts and overlooks.[12]

Buses

A fleet of vintage 1930s red buses, modernized in 2001 and called Red Jammers, or simply "Reds", continue the tradition of offering guided tours along the road.[13] The original bus drivers became affectionately known as "Gear Jammers" or simply "Jammers" since they had to jam the manual gearbox into low to safely negotiate the steepest road sections.[13] Thirty-three of the original buses were rebuilt with flexible-fuel engines which operate mainly on propane but can use gasoline, and with automatic transmissions, making the Jammer name archaic.[14][15] Modern-style shuttle buses for shorter trips and Blackfeet tour buses operate on the road as well.[16]

Cinematic appearances

Going-to-the-Sun Road is shown in the opening credits of the 1980 film The Shining, as aerial flybys of Wild Goose Island and the protagonist's car traveling along the north shore of Saint Mary Lake, through the East Side tunnel and onward, going to a mountain resort hotel for his job interview as a winter caretaker.[17]

The road is also seen briefly in the 1994 film Forrest Gump. As Forrest reminisces with Jenny he remembers running across the U.S. and remarks, "Like that mountain lake. It was so clear, Jenny. It looked like there were two skies, one on top of the other." The shots in the background are Going-to-the-Sun Road and Saint Mary Lake.[18]

See also

Major points of interest along the road from west-to-east include:

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Going-to-the-Sun Road". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- "Going-to-the-Sun Road FAQs". National Park Service. October 19, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- Scott, Tristan (2011-04-07). "Glacier's Going-to-the-Sun Road to open July 13, 2nd latest ever". Missoulian. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- "Session due on Sun Road improvement". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. July 18, 1967. p. 6.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form". National Park Service. 1983-06-16. Archived from the original on 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- "Top 10 Things...#2". National Park Service. 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Carr, p. 160.

- Carr, p. 171.

- Carr, p. 186.

- "Going-to-the-Sun Road Project". Federal Highway Administration. 2015-10-16. Archived from the original on 2015-10-27. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- "Top 10 Things...#3-7". National Park Service. 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- "On the Road Again: Glacier National Park's Red Buses" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-17. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Wille, Chris (May 5, 2002). "Classic jammers slowly returning to Glacier". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. H4.

- Siano, Joseph (September 1, 2002). "Parks take steps to clean air". Sunday Star-News. Wilmington, North Carolina. New York Times News Service. p. 9D.

- "Plan Your Visit-Getting Around". National Park Service. 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0081505/trivia?ref_=tt_trv_trv

- http://montanakids.com/cool_stories/Movies/Forrest.htm

Carr, Ethan (1998). Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture & the National Park Service. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6383-X.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Going to the Sun Road. |

- Glacier National Park official website

- Going-to-the-Sun-Road Information and Transit System

- Current road status

- Going-to-the-Sun Road: A Model of Landscape Engineering

- Visit Montana - Going-to-the-Sun Road

- Great Falls Tribune: Glacier National Park centennial timeline

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MT-67, "Going-to-the-Sun Road, West Glacier, Flathead County, MT"