Glutaraldehyde

Glutaraldehyde, sold under the brandname Cidex and Glutaral among others, is a disinfectant, medication, preservative, and fixative.[3][4][5][6] As a disinfectant, it is used to sterilize surgical instruments and other areas of hospitals.[3] As a medication, it is used to treat warts on the bottom of the feet.[4] Glutaraldehyde is applied as a liquid.[3]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pentanedial[1] | |

| Other names

Glutaraldehyde Glutardialdehyde Glutaric acid dialdehyde Glutaric aldehyde Glutaric dialdehyde 1,5-Pentanedial | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.506 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

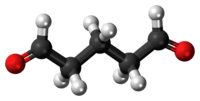

| C5H8O2 | |

| Molar mass | 100.117 |

| Appearance | Clear liquid |

| Odor | pungent[2] |

| Density | 1.06 g/mL |

| Melting point | −14 °C (7 °F; 259 K) |

| Boiling point | 187 °C (369 °F; 460 K) |

| Miscible, reacts | |

| Vapor pressure | 17 mmHg (20°C)[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | CAS 111-30-8 |

| GHS pictograms |     |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H302, H314, H317, H331, H334, H400 |

| P260, P264, P270, P271, P272, P273, P280, P284, P301+312, P330, P302+352, P332+313, P304+340, P305+351+338, P311, P403+233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | noncombustible[2] |

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

0.2 ppm (0.82 mg/m3) (TWA), 0.05 ppm (STEL) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

134 mg/kg (rat, oral); 2,560 mg/kg (rabbit, dermal) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

REL (Recommended) |

0.2 ppm (0.8 mg/m3)[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Side effects include skin irritation.[4] If exposed to large amounts, nausea, headache, and shortness of breath may occur.[3] Protective equipment is recommended when used, especially in high concentrations.[3] Glutaraldehyde is effective against a range of microorganisms including spores.[3][7] Glutaraldehyde is a dialdehyde.[8] It works by a number of mechanisms.[7]

Glutaraldehyde came into medical use in the 1960s.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10] There are a number of other commercial uses such as leather tanning.[11]

Uses

Disinfection

Glutaraldehyde is used as a disinfectant and medication.[3][4][12]

Usually applied as a solution, it is used to sterilize surgical instruments and other areas.[3]

Fixative

Glutaraldehyde is used in biochemistry applications as an amine-reactive homobifunctional crosslinker and fixative prior to SDS-PAGE, staining, or electron microscopy. It kills cells quickly by crosslinking their proteins. It is usually employed alone or mixed with formaldehyde[13] as the first of two fixative processes to stabilize specimens such as bacteria, plant material, and human cells. A second fixative procedure uses osmium tetroxide to crosslink and stabilize cell and organelle membrane lipids. Fixation is usually followed by dehydration of the tissue in ethanol or acetone, followed by embedding in an epoxy resin or acrylic resin.

Another application for treatment of proteins with glutaraldehyde is the inactivation of bacterial toxins to generate toxoid vaccines, e.g., the pertussis (whooping cough) toxoid component in the Boostrix Tdap vaccine produced by GlaxoSmithKline.[14]

In a related application, glutaraldehyde is sometimes employed in the tanning of leather and in embalming.

Wart treatment

As a medication it is used to treat plantar warts.[4] For this purpose, a 10% w/v solution is used. It dries the skin, facilitating physical removal of the wart.[15] Trade names include Diswart Solution and Glutarol.

Safety

Side effects include skin irritation.[4] If exposed to large amounts, nausea, headache, and shortness of breath may occur.[3] Protective equipment is recommended when used, especially in high concentrations.[3] Glutaraldehyde is effective against a range of microorganisms including spores.[3][7]

As a strong sterilant, glutaraldehyde is toxic and a strong irritant.[16] There is no strong evidence of carcinogenic activity.[17] Some occupations that work with this chemical have an increased risk of some cancers.[17]

Mechanism of action

A number of mechanisms have been invoked to explain the biocidal properties of glutaraldehyde.[7] Like many other aldehydes, it reacts with amines and thiol groups, which are common functional groups in proteins. Being bi-function, it is also a potential crosslinker.[18]

Production and reactions

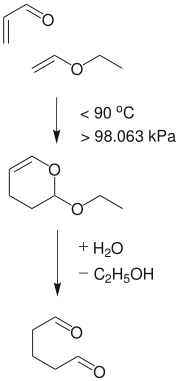

Glutaraldehyde is produced industrially by the oxidation of cyclopentene. Alternatively it can be made by the Diels-Alder reaction of acrolein and vinyl ethers followed by hydrolysis.[19]

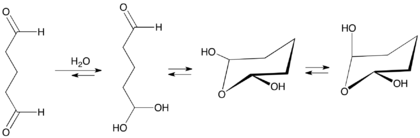

Like many other dialdehydes, (e.g., glyoxal) and simple aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde), glutaraldehyde converts in aqueous solution to various hydrates that in turn convert to other equilibrating species.[20][19]

Monomeric glutaraldehyde polymerizes by aldol condensation reaction yielding alpha, beta-unsaturated poly-glutaraldehyde. This reaction usually occurs at alkaline pH values.

History and culture

Glutaraldehyde came into medical use in the 1960s.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[10] There are a number of other commercial uses such as leather tanning.[11]

A glutaraldehyde solution of 0.1% to 1.0% concentration may be used as a biocide for system disinfection and as a preservative for long-term storage. It is a sterilant, killing endospores in addition to many microorganisms and viruses.[21]

As a biocide, glutaraldehyde is a component of hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") fluid. It is included in the additive called Alpha 1427.[22] Bacterial growth impairs extraction of oil and gas from these wells. Glutaraldehyde is pumped as a component of the fracturing fluid to inhibit microbial growth.

References

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 907. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards -Glutaraldehyde". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 323, 325. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 825. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Bonewit-West, Kathy (2015). Clinical Procedures for Medical Assistants. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 96. ISBN 9781455776610.

- Sullivan, John Burke; Krieger, Gary R. (2001). Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 601. ISBN 9780683080278.

- Fraise, Adam P.; Maillard, Jean-Yves; Sattar, Syed (2012). Russell, Hugo and Ayliffe's Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. John Wiley & Sons. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9781118425862. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- Pfafflin, James R.; Ziegler, Edward N. (2006). Encyclopedia of Environmental Science and Engineering: A-L. CRC Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780849398438.

- Booth, Anne (1998). Sterilization of Medical Devices. CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781574910872. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Rietschel, Robert L.; Fowler, Joseph F.; Fisher, Alexander A. (2008). Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. PMPH-USA. p. 359. ISBN 9781550093780. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- Bonewit-West, Kathy (2015). Clinical Procedures for Medical Assistants. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 96. ISBN 9781455776610. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- Karnovsky, M.J. (1965). A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolality for use in electron microscopy. Journal of Cell Biology 27: 137A–138A

- Boostrix prescribing information Archived 2011-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, ©2009, GlaxoSmithKline

- NHS Choices: Glutarol Archived 2015-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS) (a federal government site) > OSH Answers > Diseases, Disorders & Injuries > Asthma Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Document last updated on February 8, 2005

- Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Glutaraldehyde Archived 2012-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- H. Uhr; B. Mielke; O. Exner; K. R. Payne; E. Hill (2013). "Biocides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_563.pub2.

- Christian Kohlpaintner; Markus Schulte; Jürgen Falbe; Peter Lappe; Jürgen Weber (2008). "Aldehydes, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_321.pub2.

- Whipple Earl B.; Ruta Michael (1974). "Structure of Aqueous Glutaraldehyde". J. Org. Chem. 39: 1666–1668. doi:10.1021/jo00925a015.

- HCC lecture notes, 15 Archived 2015-05-02 at the Wayback Machine: Control of microorganisms Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Morgantown Utility Board. "Fracking Fluid Additives - Fracking Fluid MSDS's". Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.. Links to documents, including Alpha 1427 Material Safety Data Sheet

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory - Glutaraldehyde Fact Sheet

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health - Glutaraldehyde

- NIST WebBook

- "Glutaraldehyde". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.