Glacier View Dam

Glacier View Dam was proposed in 1943 on the North Fork of the Flathead River, on the western border of Glacier National Park in Montana. The 416-foot (127 m) tall dam, to be designed and constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the canyon between Huckleberry Mountain and Glacier View Mountain, would have flooded in excess of 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) of the park. In the face of determined opposition from the National Park Service and conservation groups, the dam was never built.

| Glacier View Dam | |

|---|---|

Glacier View Dam as proposed | |

Location of Glacier View Dam in Montana | |

| Location | Flathead County, near West Glacier, Montana, USA |

| Coordinates | 48°36′42″N 114°09′11″W |

| Construction began | Proposal only |

| Operator(s) | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | North Fork Flathead River |

| Height | 416 ft (127 m) |

| Length | 2,100 ft (640 m) |

| Spillway type | Gated side-channel spillway |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Glacier View Reservoir |

| Total capacity | 3,160,000 acre feet (3.90 km3) |

| Surface area | 48 square miles (120 km2) |

| Power Station | |

| Turbines | 3 x 70 MW turbines |

| Installed capacity | 210 MW |

Proposal

The Glacier View project was proposed after an earlier proposal by the Corps of Engineers and the Bonneville Power Administration to raise the level of Flathead Lake by increasing the height of Kerr Dam at its outlet was rejected, following local protests.[1] Located in a relatively unpopulated area, the Glacier View reservoir would have flooded lower Camas Creek and would have raised the level of Logging Lake by 50 feet (15 m), inundating much of the winter range for the park's white-tailed deer, elk, mule deer and moose.[2] The proposed reservoir was to extend nearly to the Canada–US border,[3] at an estimated cost of $94,962,000.[4] The dam was supported by Montana Representative Mike Mansfield and Flathead Valley interests, but was opposed by former Senator Burton K. Wheeler, local ranchers, the National Park Service, the Glacier Park Hotel Company, the Sierra Club, Society of American Foresters and the Audubon Society. Public hearings were held in 1948 and 1949.[5] Turnout at the 1948 hearings at Kalispell was influenced by extensive flooding then occurring in the Flathead Valley.[6] Exploratory drilling took place in 1944 and 1945 at Glacier View and Foolhen Hill.[1] The project was terminated by a joint memorandum between the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of the Army on April 11, 1949, but Mansfield introduced an unsuccessful bill later in the year directing the Corps of Engineers to proceed with the dam,[7] stating that the dam "would not affect the beauty of the park in any way but would make it more beautiful by creating a large lake over ground that ... has no scenic attraction."[8] The Corps of Engineers report on the project noted:

The park lands that will be inundated and required for freeboard of 5 feet above normal pool elevation amounts to 10,175 acres (4,118 ha), or about 1 percent of the total Glacier National Park area. This area does not lie within the rugged, glacier-covered portion of the park for which it is noted, but rather is on the western boundary line, in a little-used valley. The reservoir area is covered with lodge-pole pine, an inferior species of limited use. Other species of pine timber such as ponderosa pine, are predominate above the normal full reservoir and will not be injured by the project. Other lands inundated or required by this project are in private, State and United States Forest Service ownership and hence should be of no concern to the Park Service. Although there would be some effect on the wildlife in the area, the construction of Glacier View Reservoir would inconvenience but relatively few people as it is situated in a sparsely populated area.[2]

Park Service Director Newton B. Drury responded:

The effects of the proposed impoundment of the North Fork of the Flathead River upon Glacier National Park would be extraordinarily serious upon the very values with the National Park Service is obliged by law, and expected by the public, to protect ... The flooding of park land would reduce the winter range of [white-tailed deer] by 56 percent. In order to prevent extensive starvation, it would be necessary for the Park Service to undertake the slaughter of most of these animals ... We cannot afford, except for the most compelling reasons — which we are convinced do not exist in this case — to permit this impairment of one of the finest properties of the American people.[2]

Drury went on to state that 19,460 acres (7,880 ha) of land would be flooded, including virgin Ponderosa pine.[6] In order to show that the area was of recreational value, the Park Service constructed the Camas Creek Road through the area.[5]

The dam was opposed by the Park Service and conservation organizations on principal as an intrusion into lands that had been made inviolate by their inclusion in a national park, with about a third of the reservoir located on Park Service lands.[9] The precedent established at Hetch Hetchy in Yosemite National Park was not to be repeated. A similar, more difficult fight followed over the proposed Echo Park Dam in Dinosaur National Monument.[7]

Related projects

A related project, the Paradise project on the Clark Fork River just below its confluence with the Flathead, was opposed by local interests.[10] The Paradise project was considered by the Corps of Engineers to be a more desirable project than Glacier Point, but was considered by the Corps to be difficult to develop compared to Glacier View, given the developed nature of the flooded area proposed at Paradise versus the relatively unpopulated Glacier View region. Other proposed dams were the Smoky Range, Canyon Creek and Spruce Park dams, none of which were built. Hungry Horse Dam was, however, completed in 1953 by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation on the South Fork of the Flathead. The Spruce Park reservoir to the south of the park was proposed to have been connected to the Hungry Horse reservoir, with a power generation plant at the conduit's discharge.[8] Paradise Dam is described by the Corps of Engineers as preferable from the point of view of the overall plan, standing on both the Clark Fork River and the Flathead, but the flooding of towns and productive agricultural lands stirred intense local opposition.[11]

The 1950 Corps of Engineers report that detailed the Glacier View project also mentioned the potential of the Middle Fork Flathead River for development, and projected a dam at Belton, with a 1,190,000-acre-foot (1.47 km3) reservoir behind a dam developing 330 feet (100 m) of hydraulic head, for a potential generating capacity of 152 MW. As the Middle Fork forms the southwest boundary of Glacier National Park, any reservoir on the Middle Fork near Belton would necessarily flood portions of the park. With the rejection of the Glacier View project, the Belton project never progressed beyond its listing as a potential project.[12]

Description

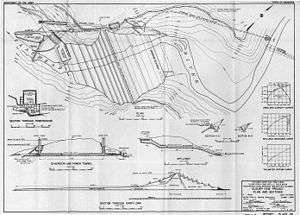

The proposed Glacier View Dam was to be a 416-foot (127 m) high, 2,100-foot (640 m) long earth embankment dam, impounding a reservoir with a capacity of 3,160,000 acre feet (3.90 km3) and covering an area of about 48 square miles (120 km2). A gated spillway was to be built to the north side, feeding a tunnel through the abutment. A powerplant at the toe of the dam was planned to house three 70 MW generating units,[9] fed by an intake tower and equipped with a surge tank.[13] The chosen site was to be at river mile 176.5. Alternate sites at Fool Hen Hill (river mile 167) and Bad Rock Canyon (river mile 150) were rejected. The Fool Hen Hill site was found to have a permeable alluvial channel in the right abutment. The Bad Rock Canyon site would have been on the main stem of the Flathead and was also determined to have poor abutment rock, as well as alluvial deposits on the valley floor reaching up to 300 ft (91 m) deep. It would have flooded the Hungry Horse damsite, which was under construction, as well as Lake McDonald in the park.[6]

Present

The Camas Road joins the Outside North Fork Road just to the east of the damsite. The Forests and Fire Nature Trail is just upstream from the site. The Logging Creek Ranger Station and the small town of Polebridge lie within the proposed reservoir. Within the park, the lower reaches of Camas Creek, Quartz Creek, Bowman Creek and Akokala Creek would have been flooded, along with most of Logging Creek and Logging Lake.[14]

References

- Robinson, Donald H. "Chapter 3: History as a National Park". Through the Years in Glacier National Park: An Administrative History. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report 1950, p. 153

- "61st Congress, 2d Session, House Document No. 581, Report: Columbia River and Tributaries, Northwestern United States". Army Corps of Engineers. March 20, 1950. p. map. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, p. 15

- Buchholtz, C.W. (1976). Chapter 6:Guardians of Glacier. Man in Glacier. Glacier Natural History Association. ISBN 0-916792-01-3. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, p. 152

- DeVoto, Bernard Augustine (2005 (article appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in 1950). "Shall We Let Them Ruin Our National Parks?". In Muller, Edward K. (ed.). DeVoto's West: History, Conservation and the Public Good. Ohio University Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-8040-1072-2. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Forest Service Administration, 1905-1960". Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960. Forest History Society. January 18, 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, p. 150

- Husted, James. "The Glacier View Dam Project". Planning and Civic Comment, Vol. 15. National Conference on City Planning.

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, p. 330

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, p. 303

- Corps of Engineers 1950 Columbia River and Tributaries Report, "Glacier View Project Plan and Sections"

- "Glacier National Park Map". National Park Service. Retrieved 5 June 2011.