Germantown (town), New York

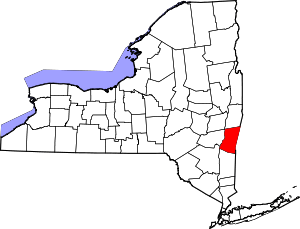

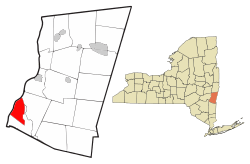

Germantown is a town in Columbia County, New York, United States. The population was 1,954 at the 2010 census.[1] Germantown is located in the southwest part of the county, along the east side of the Hudson River.

Germantown, New York | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Town hall, 2013 | |

Location of Germantown, New York | |

| Coordinates: 42°08′03″N 73°52′16″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Columbia |

| Established | 1788 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town Council |

| • Town Supervisor | Robert Beaury (R) |

| • Town Council | Members' List

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.9 sq mi (36.1 km2) |

| • Land | 12.1 sq mi (31.3 km2) |

| • Water | 1.8 sq mi (4.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 249 ft (76 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,954 |

| • Density | 161/sq mi (62.3/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 12526 |

| Area code(s) | 518 Exchange: 537 |

| FIPS code | 36-28772 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0978998 |

| Website | www |

History

Early Indigenous History

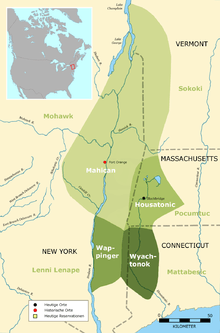

The area that is currently known as Germantown was originally occupied by the Mohicans. In the early eighteenth century, Hendrick Aupaumut recorded the movement of his people that brought them to settle along the rivers that would later be named the Delaware and Hudson. Those who had continued north settled in the valley of the river they named the Mahicannituck, meaning the Waters That Are Never Still. They named themselves the Muh-he-con-neok after the river, a name that eventually evolved to the present day Mohican or Mahican.

The Mohicans settled in the valley, building wigwams and longhouses. The river and woodlands were abundant with life and food, which they supplemented with the corn, beans, and squash they grew. Mohican women were usually in charge of this agriculture, along with the homes and children, while men traveled to fish, hunt, or serve as warriors.[2][3][4]

During this time, Mohican territory extended from Manhattan to Lake Champlain, on both sides of the Mahicannituck, east to Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont, and west to Scoharie Creek.

Colonization and European-Mohican Relations

In September 1609, Henry Hudson, a trader for the Dutch, sailed up the Mahicannituck. The valley was rich with the beavers and otters whose fur the Dutch coveted, and in 1614 a trading post was established. As the fur trade expanded, making desired furs harder to find, tensions arose between the Mohicans and the Mohawk, who each sought to maintain their share in the fur trade and relations with European allies. Wars and their effects contributed to the loss of Mohican land to the point where territory in the Hudson Valley dwindled almost completely by the end of the seventeenth century. Mohicans were especially affected by European wars such as King Philip’s War where soldiers from Massachusetts and Connecticut attacked Mohicans. In general after war, Mohicans sold land to the Dutch in exchange for needed resources lost in the destruction of indigenous farming and preserved resources. As more and more Europeans arrived and settled on the land, the Mohicans’ self-reliance and reliance on the land was eroded by increased dependency on the settlers and their provisions. Settlers began dividing the land, establishing fences and boundary lines. Eventually, the Mohicans were driven from their territory west of the Mahicannituck and continued to move further east in the early 1700s.[5]

Robert Livingston, a Scots immigrant, bought thousands of acres from the Native Americans. In 1683, Mohicans sold the first land parcel along the Roelof Jansen Kill to Livingstone in exchange for goods as well as rights to hunting and fishing in the area. While Livingstone received a Mohican deed to the Tachkanick settlement in 1685, he only built his house in 1689. These exchanges were the beginning of a trade relationship that lasted through 1768.[6] He owned a total of 160,240 acres (64,850 ha) at what became Livingston Manor.

Moravian-Mohican Relations

In the summer of 1740, the first Moravian mission was established in the Mohican village of Shekomeko. Before that, Moravian missionary Christian Henry Rauch approached two Mohican leaders, Maumauntissekun (AKA Shabash) and Wassamapah who were sojourning in NYC. Rauch wanted them to help bring Christianity to Mohican settlements. Maumauntissekun had a vision in 1739 where he and his Indian brethren laid dead in the woods. Because they suffered from alcoholism, he believed in the need for religion and temperance. Maumauntissekun agreed to bring Rauch to his town, Shekomeko. Initially, many Mohicans were skeptical of Rauch’s presence because Mohican land had been bought in such great quantities by Europeans. Nevertheless, Maumauntissekun was among the first three Shekomeko residents to be baptized on Feb 11, 1742. Maumauntissekun then became known as Abraham of Shekomeko.[7]

The Moravians lived among Mohicans in Dutchess County and Connecticut’s Housatonic Valley. Many Moravians missionaries learned Mohican languages, while often in areas of strong English and German influence, they did not. Children of Mohican converts learned to read and write in Moravian schools. By the mid-eighteenth century, much of Mohican territory was divided by colonial powers, leaving many without much semblance of spatial surroundings as they had a century before. Although many Mohicans were divided on the matter, there were Mohicans who adapted to a new way of life by converting to Christianity. Families often sent their children to be baptized and raised at Moravian headquarters in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania due to high mortality rates of children from European diseases and war.[8]

In the 1740s there were regional Indian raids on European settlements in New York and Massachusetts. Settlers believed that the French in Canada supplied Indians with weapons. Moravian missionaries were perceived as both allies to Canada and Indians and were thus accused of disloyalty for fomenting the uprisings. The last straw was drawn in early 1744 when Moravian missionaries refused to enter colonial militias. The New York government issued a September 1744 order that discontinued Moravian missionary activities in New York.[9]

Mohican-Settler Land Disputes

In the 1720s, white settlers began to survey Dutchess County land that they claimed according to exchanges originating from the Great Nine Partners Patent. The latter was a landholding of between 8 and 10 miles in width from East of the Hudson almost to Connecticut at Oblong Patent. It was granted to white settlers in May of 1697 and the result of negotiations with Indians in eight grants from the Little Nine Partners Patent signed in April of 1706.[10]

Abraham of Shekomeko (formerly known as Maumauntissekun or Shabash) protested the claims but was still willing to sell some land. His grievance was based on Mohican tradition: land that was not used is open for his people to continue hunting and fishing in the area. The Dutchess County territory being surveyed was unoccupied by white settlers for over four decades, making European claims de jure. The Mohicans, on the other hand, had been hunting and farming on the land for over two decades. According to a missionary memorandum recorded in 1743, Abraham went to New York City in 1724 where the governor promised to pay for Mohican land and leave them with a square mile for Mohican settlement. In September of 1743 that square mile was divided by white settlers. In response, Abraham wrote to the governor disputing the unlawful claims. He tried to prove Mohican ownership by producing witnesses to the Little Nine Partners and even sent a petition around Shekomeko. In the end, the land was divided, and Abraham moved from the village site while Shekomeko was claimed by a proprietor.[11]

Founding of Germantown

In 1710, Robert Livingstone sold 6,000 acres (2,400 ha) of his property to Anne, Queen of Great Britain, for use as work camps and resettlement of Palatine German refugees.[12] Some 1,200 persons were settled at work camps to manufacture naval stores and pay off their passage as indentured labor.[13] Known as "East Camp", the colony had four villages: Hunterstown, Queensbury, Annsbury, and Haysbury.[14] The area was later renamed "Germantown". In 1775 Germantown was formed as a "district".[15] Germantown was one of the seven original towns of Columbia County established by an act passed March 7, 1788. (The others were: Kinderhook, Canaan, Claverack, Hillsdale, Clermont, and Livingston).[16]

In March 1845, a boat-load of people from East Camp, who had been to Hudson to make purchases, was run over first by a scow, and then by the steamboat South America. All nine individuals were lost.[17]

The Barringer–Overbaugh–Lasher House, Clermont Manor, Clermont Estates Historic District, Charles H. Coons Farm, Dick House, German Reformed Sanctity Church Parsonage, Hudson River Heritage Historic District, Stone Jug, and Simeon Rockefeller House are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[18][19]

Removal

During the Revolution the Mohicans supported the colonists but after the war concluded it became apparent that the Mohicans were not welcome in their village. The Oneida offered them a portion of land and in the mid-1780s they began to move to New Stockbridge. Although the community thrived and the population grew steadily, land companies, hoping to make a profit from the land inhabited by Indigenous communities, proposed that New York State remove all Native Americans from within its borders. In 1822 agents from New York, missionaries, and commissioners from the War Department negotiated with the Menominee and Ho-Chunk communities of Wisconsin for a tract of land on which to relocate the indigenous tribes of New York. In the following years, members of the community was relocated to Wisconsin and settled on the reservation land.[20][21][22]

The Stockbridge-Munsee Today

Today, the community is still located on the reservation in Shawano County, Wisconsin where they were forcibly relocated to in the mid-1800s, but enrolled members live throughout the state, the United States, and the world. 1,500 people, most of whom live in Wisconsin, trace their ancestry back to the people who first inhabited the Hudson Valley and are part of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation. Some of the community members live on trust land in Wisconsin assigned for their use. Other members of the nation live on privately owned lands within the boundaries of the reservation.

The community has grown; mobile homes, apartments, and permanent homes have been added to the original housing, a family center and a health and wellness center have been built, and the Pine Hills Golf Course has expanded. The nation has established The North Star Mohican Casino. They have also set up a Tribal Historic Preservation Office on the campus of the Sage Colleges in Albany to increase their presence in the Hudson Valley.[23] Members of the Nation continue to visit the Hudson Valley, to gather historical information from local libraries and archives, and visit sacred sites.[24][25]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 13.9 square miles (36.1 km2), of which 12.1 square miles (31.3 km2) is land and 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2), or 13.07%, is water. The west town line, marking the center of the Hudson River, is the border of Greene and Ulster counties.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1820 | 891 | — | |

| 1830 | 967 | 8.5% | |

| 1840 | 969 | 0.2% | |

| 1850 | 1,023 | 5.6% | |

| 1860 | 1,353 | 32.3% | |

| 1870 | 1,393 | 3.0% | |

| 1880 | 1,608 | 15.4% | |

| 1890 | 1,683 | 4.7% | |

| 1900 | 1,686 | 0.2% | |

| 1910 | 1,649 | −2.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,424 | −13.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,462 | 2.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,427 | −2.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,418 | −0.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,504 | 6.1% | |

| 1970 | 1,782 | 18.5% | |

| 1980 | 1,922 | 7.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,010 | 4.6% | |

| 2000 | 2,018 | 0.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,954 | −3.2% | |

| Est. 2014 | 1,906 | [26] | −2.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] | |||

As of the census[28] of 2000, there were 2,018 people, 831 households, and 546 families residing in the town. The population density was 166.0 people per square mile (64.1/km2). There were 984 housing units at an average density of 81.0 per square mile (31.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.93% White, 1.14% Black or African American, 0.15% Native American, 0.45% Asian, 0.40% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.29% of the population.

There were 831 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.7% were married couples living together, 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.2% were non-families. 28.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 23.1% under the age of 18, 6.0% from 18 to 24, 27.1% from 25 to 44, 25.8% from 45 to 64, and 18.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.5 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $42,195, and the median income for a family was $50,885. Males had a median income of $36,806 versus $26,250 for females. The per capita income(which is also known as income per person) for the town was $22,198. About 5.0% of families and 7.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.3% of those under age 18 and 5.7% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

- Corbin Bernsen, actor

- Dow Hover, New York State executioner

- Sonny Rollins, saxophonist

- Oliver Stone, film director, has a summer home here

Communities and locations in Germantown

- Cheviot – A hamlet near the Hudson River, south of Germantown hamlet.

- Germantown – The hamlet of Germantown is located near the Hudson River on Route 9G.

- North Germantown – A hamlet on Route 9G north of Germantown hamlet.

- Palatine Park – A park northeast of Germantown hamlet.

- Viewmont – A hamlet on the south town line.

References

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Germantown town, Columbia County, New York". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- "Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians". www.mohican.com. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (1994). The Mohicans and their land, 1609-1730 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 0935796495. OCLC 30473288.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 193009812X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Nine Partners, Dutchess County". www.newyorkroots.org. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1-930098-12-X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "About Germantown", Town of Germantown

- Knittle, Walter Allen (1965). Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8063-0205-4.

- Otternesss, Philip. Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Chap. 5, Cornell University Press, 2013 ISBN 9780801471162

- Ellis, Franklin. Germantown, Columbia County, New York, 1878

- "History", Columbia County

- Ellis, Germantown, "Road Districts, 1808".

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 12/01/14 through 12/05/14. National Park Service. 2014-12-12.

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (1994). The Mohicans and their land, 1609-1730 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 0935796495. OCLC 30473288.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dunn, Shirley W. (Shirley Wiltse), 1928- (2000). The Mohican world, 1680-1750 (1st ed.). Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 193009812X. OCLC 44885261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians". www.mohican.com. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- "Mohican Tribal Historic Preservation Office Established on Campus". horizons.sage.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Levine, David (2020). The Hudson Valley: The First 250 Million Years: A Mostly Chronological and Occasionally Personal History. United States: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 12–18. ISBN 9781493047901.

- "Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians". www.mohican.com. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Germantown, New York. |