George Sterling

George Sterling (December 1, 1869 – November 17, 1926) was an American writer based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area and Carmel-by-the-Sea. He was considered a prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the first quarter of the twentieth century. His work was admired by writers as diverse as Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis, but is largely neglected today.

George Sterling | |

|---|---|

Sterling shortly before his death in 1926[2] | |

| Born | George Sterling December 1, 1869 Sag Harbor, Suffolk County, New York City |

| Died | November 17, 1926 (aged 57) San Francisco, California |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, playwright |

Life and career

Sterling was born in Sag Harbor, New York, the eldest of nine children. His father was Dr. George A. Sterling, a physician who determined to make a priest of one of his sons, and George was selected to attend, for three years, St. Charles College in Maryland. He was instructed in English by poet John B. Tabb. His mother Mary was a member of the Havens family, prominent in Sag Harbor and the Shelter Island area. Her brother, Frank C. Havens, Sterling's uncle, went to San Francisco in the late 19th century and established himself as a prominent lawyer and real estate developer. Sterling eventually followed him to the West in 1890 and worked as a real estate broker in Oakland, California. With the publication of his small volume of poetry in 1903, The Testimony of the Sun and Other Poems, he quickly became a hero among the East Bay literati and artists, some of whom included Joaquin Miller, Jack London, Xavier Martinez, Harry Leon Wilson, Perry H. Newberry, Henry Lafler, Gelett Burgess, and James Hopper.

In 1905 Sterling moved 120 miles south to Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, an undeveloped coastal paradise, and soon established a settlement for like-minded Bohemian writers and other children of the counterculture.[4] A parallel colony of painters was also developing in this enclave. Carmel had been discovered by Charles Warren Stoddard and others, but Sterling made it world-famous. His aunt Mrs. Havens purchased a home for him in Carmel Pines where he lived for nine years. In addition to the Bay Area residents mentioned above, Sterling managed to attract, as either visitors or semi-permanent residents, the satirical iconoclast Ambrose Bierce, novelist Mary Austin,[5] art photographer Arnold Genthe, writer Clark Ashton Smith, and poet Robinson Jeffers. When a firestorm of controversy followed Sterling's publication of A Wine of Wizardry in the Cosmopolitan magazine of September 1907, other rebels flocked to Carmel, including Upton Sinclair and the MacGowan sisters. The suicide by poison of the young poet Nora May French in Sterling's home drew national press coverage.[6][7][8][9] The suicide of Sterling's wife by cyanide only added fuel to the flames. Sterling's own diaries and correspondence reveal a more sedate, but still Bohemian community.[10] He often volunteered at Carmel's Forest Theatre and once played a starring role in Mary Austin's play The Fire.[4] He is depicted twice in Jack London's novels: as Russ Brissenden in the autobiographical Martin Eden (1909) and as Mark Hall in The Valley of the Moon (1913).

Kevin Starr (1973) wrote:

The uncrowned King of Bohemia (so his friends called him), Sterling had been at the center of every artistic circle in the San Francisco Bay Area. Celebrated as the embodiment of the local artistic scene, though forgotten today, Sterling had in his lifetime been linked with the immortals, his name carved on the walls of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition next to the great poets of the past.

Joseph Noel (1940) says that Sterling's poem, A Wine of Wizardry,[11] has "been classed by many authorities as the greatest poem ever written by an American author."

According to Noel, Sterling sent the final draft of A Wine of Wizardry to the normally acerbic and critical Ambrose Bierce. Bierce said "If I could find a flaw in it, I should quickly call your attention to it... It takes the breath away."

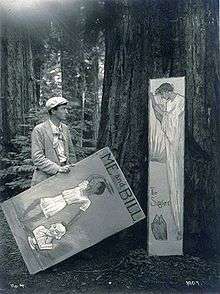

Sterling joined the Bohemian Club and acted in their theatrical productions each summer at the Bohemian Grove.[12] For the main Grove play in 1907, the club presented The Triumph of Bohemia, Sterling's verse drama depicting the battle between the "Spirit of Bohemia" and Mammon for the souls of the grove's woodmen.[13] Sterling also supplied lyric for the musical numbers at the 1918 Grove play.[12]

Bierce, who acclaimed Sterling's poem The Testimony of the Suns, in his "Prattle" column in William Randolph Hearst's San Francisco Examiner, arranged for the publication of A Wine of Wizardry in the September 1907 number of Cosmopolitan, which afforded Sterling some national notice. In an introduction to the poem, Bierce wrote "Whatever length of days may be according to this magazine, it is not likely to do anything more notable in literature than it accomplished in this issue by the publication of Mr. George Sterling's poem, 'A Wine of Wizardry.'" Bierce wrote to Sterling, "I hardly know how to speak of it. No poem in English of equal length has so bewildering a wealth of imagination. Not Spencer himself has flung such a profusion of jewels into so small a casket".

Sterling fell into drinking and his wife departed. Noel, a personal acquaintance, says that when he began the poem, Sterling "was persuaded that there was another world than that we know. He repeated this to me so frequently that it became a trifle tiresome. Of the means he employed to get a glimpse of that other world, I am not so sure." He observes that "many before Sterling had used narcotics to this end;" that "George, a doctor's son, had always had access to whatever drugs he fancied;" says that Sterling's wife said "that George had purloined a great quantity of opium from his brother Wickham," and speaks of "internal evidence in the poem" in which "Sterling writes his Fancy awakened with a 'brow caressed by poppybloom.'" Despite all this, Noel makes a point of saying "there is no direct evidence that Sterling used narcotics."

Sterling also wrote for children The Saga of the Pony Express.

Despite such famous mentors as Bierce and Ina Coolbrith, and his long association with London, Sterling himself never became well known outside California.

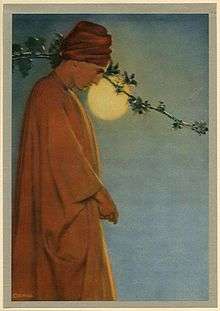

Sterling's poetry is both visionary and mystical, but he also wrote ribald quatrains that were often unprintable and left unpublished. His style reflects the Romantic charm of such poets as Shelley, Keats and Poe, and he provided guidance and encouragement to the similarly-inclined Clark Ashton Smith at the beginning of Smith's own career.

Sterling carried a vial of cyanide for many years. When asked about it he said, "A prison becomes a home if you have the key".[14] Finally in November 1926, Sterling used it at his residence at the San Francisco Bohemian Club after not receiving an expected visit from H.L. Mencken. Kevin Starr wrote that "When George Sterling's corpse was discovered in his room at the Bohemian Club... the golden age of San Francisco's bohemia had definitely come to a miserable end."

Sterling's most famous line was delivered to the city of San Francisco, "the cool, grey city of love!".[15]

Memorials

- Sterling Avenue in Berkeley is named for George Sterling.

- It is thought that Sterling Avenue in Alameda is named for George Sterling.

- A stone bench was dedicated to Sterling on June 25, 1926 at the crest of Hyde Street on Russian Hill. In 1982, the park the bench was originally located in was named "George Sterling Park".[16]

Writings

Poetry

- The Testimony of the Suns and Other Poems (San Francisco: W. E. Wood, 1903; San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1904, 1907; St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Scholarly Press, 1970)

- A Wine of Wizardry and Other Poems (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1909).

- The House of Orchids and Other Poems (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1911).

- Beyond the Breakers and Other Poems (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1914).

- Ode on the Opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1915).

- The Evanescent City (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1915).

- The Caged Eagle and Other Poems (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1916).

- Yosemite: An Ode (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1916).

- The Binding of the Beast and Other War Verse (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1917).

- Thirty-Five Sonnets (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1917).

- To a Girl Dancing (San Francisco: Grabhorn, 1921).

- Sails and Mirage and Other Poems (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1921).

- Selected Poems (New York: Henry Holt, 1923; San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1923).

- Strange Waters (San Francisco: Paul Elder [?], 1926).

- The Testimony of the Suns, Including Comments, Suggestions, and Annotations by Ambrose Bierce: A Facsmile of the Original Typewritten Manuscript (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1927).

- Sonnets to Craig, Upton Sinclair, ed. (Long Beach, Calif.: Upton Sinclair, 1928; New York: Albert & Charles Boni, 1928).

- Five Poems ([San Francisco]: Windsor Press, 1928).

- Poems to Vera (New York: Oxford University Press, 1938).

- After Sunset, R. H. Barlow, ed. (San Francisco: John Howell, 1939).

- A Wine of Wizardry and Three Other Poems, Dale L. Walker, ed. (Fort Johnson: "a private press," 1964).

- George Sterling: A Centenary Memoir-Anthology, Charles Angoff, ed. (South Brunswick and New York: Poetry Society of America, 1969).

- The Thirst of Satan: Poems of Fantasy and Terror, S. T. Joshi, ed. (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2003).

- Complete Poetry, S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz, eds. (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2013).

Plays

- The Triumph of Bohemia: A Forest Play (San Francisco: Bohemian Club, 1907).

- with Henry Anderson Lafler: A Masque of the Cities ([Oakland]: [Oakland Commercial Club], 1913).

- with Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The Play of Everyman (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1917; Los Angeles: Primavera Press, 1939).

- Lilith: A Dramatic Poem (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1919; San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1920; New York: Macmillan, 1926).

- Rosamund: A Dramatic Poem (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1920).

- Truth (Chicago: Bookfellows, 1923; San Francisco: Bohemian Club, 1926).

Songs

- with music by Lawrence Zenda (Rosaliene Travis, pseud.): Songs (San Francisco: Sherman, Clay, 1916, 1918, 1928).

- with music by Lawrence Zenda (Rosaliene Travis, pseud.): "You Are So Beautiful" (San Francisco: Sherman, Clay, 1917).

- "We're A-Going" (San Francisco: Sherman, Clay, 1918).

- with music by John H. Densmore: "Love Song" (New York: G. Schirmer, 1926).

- with additional verses contributed by Jack London, Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Gelett Burgess, and undetermined others: The Abalone Song (San Francisco: Albert M. Bender [Grabhorn Press], 1937; San Francisco: Windsor Press, 1943; Los Angeles: Tuscan Press, 1998).

Nonfiction

- Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1926).

Fiction

- Babes in the Wood (San Francisco: Vince Emery, 2020).

Letters

- Give a Man a Boat He Can Sail: Letters of George Sterling, James Henry, Ed. (Detroit: Harlo, 1980).

- From Baltimore to Bohemia: The Letters of H. L. Mencken and George Sterling, ed. S. T. Joshi (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University, 2001).

- Dear Master: Letters of George Sterling to Ambrose Bierce, 1900–1912, Roger K. Larson, ed. (San Francisco: Book Club of California; 2002).

- The Shadow of the Unattained: The Letters of George Sterling and Clark Ashton Smith, David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi, eds. (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2005).

Volumes edited by Sterling

- with Bertha Clark Pope: The Letters of Ambrose Bierce (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1922).

- Although uncredited, Sterling was co-editor of this volume and wrote "A Memoir of Ambrose Bierce" for it.

- with Genevieve Taggard and James Rorty, Continent's End (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1925).

References

- Notes

- O'Day, Edward F. (December 1927). "1869–1926". Overland Monthly. LXXXV (12): 357–359.

- O'Day, Edward F. (December 1927). "1869–1926". Overland Monthly. LXXXV (12): 357–359.

- Dear Master: Letters of George Sterling to Ambrose Bierce, 1900–1912, Roger K. Larson, ed. (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 2002), p. 65.

- Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 47, 49–50, 54, 58–59, 61, 68, 90, 124, 137, 691. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)).

- See Austin, Mary, "George Sterling at Carmel", The American Mercury May 1927, pp. 65–72.

- San Francisco Examiner: November 15, 1907, pp.1f; November 17, 1907, p.54.

- San Francisco Call: November 15, 1907, pp.1f; November 16, 1907, pp.1f.

- San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 1907, pp. 1f.

- The Oakland Tribune, November 15, 1907, p.4.

- George Sterling, Diaries, 1905–1913 (unpublished manuscript), George Sterling Correspondence and Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- A Wine of Wizardry at www.idiom.com

- Mencken, Henry Louis; Sterling, George; Joshi, S. T. From Baltimore to Bohemia: the letters of H.L. Mencken and George Sterling, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 2001, p. 252. ISBN 0-8386-3869-4

- Weir, David. Decadent culture in the United States: art and literature against the American grain, 1890–1926, SUNY Press, 2007, p. 144. ISBN 0-7914-7277-9

- The Documentary "The Gospel According to Philip K. Dick"

- The Cool, Grey City of Love, by George Sterling Archived September 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at alangullette.com

- "George Sterling Park". San Francisco Parks Alliance. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- Bibliography

- Benediktsson, Thomas E. (1980). George Sterling. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7313-4.

- Cusatis, John (2006). "George Sterling." Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poets and poetry, Volume 5, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishers, 1530–1531.

- Cusatis, John (2010) "Kindred Poets of Carmel: The Philosophical and Aesthetic Affinities of George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers" Jeffers Studies, Volume 13, Number 1 & 2, 1–11.

- Joshi, S. T. (2008). "George Sterling: Prophet of the Suns," chapter 1 in Emperors of Dreams: Some Notes on Weird Poetry. Sydney: P'rea Press. ISBN 978-0-9804625-3-1 (pbk) and ISBN 978-0-9804625-4-8 (hbk).

- Noel, Joseph (1940). Footloose in Arcadia. New York: Carrick and Evans.

- Parry, Albert (1933, first edition). "Lovely Chaos in Carmel and Taos", chapter 20 within Garretts & Pretenders: A History of Bohemianism in America, republished in 1960 and 2005, Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 1-59605-090-X

- Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California Dream 1850–1915. Oxford University Press. 1986 reprint: ISBN 0-19-504233-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Sterling. |

- George-Sterling.org Collected works, image gallery, bibliography and critical articles.

- A George Sterling Page: A brief biography of Sterling.

- George Sterling, Poet: A page by the poet's grand niece.

- George Sterling (1869–1926): A collection of Sterling's poems; notes on memorial glade in San Francisco.

- George Sterling: Poet and Friend by Clark Ashton Smith

- 5 short radio episodes from Sterling's poems at California Legacy Project.

- Guide to the Collection of George Sterling Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Finding aid to George Sterling papers, 1916-1943, at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Free scores by George Sterling at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Works by or about George Sterling at Internet Archive

- Works by George Sterling at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- George Sterling at Find a Grave