Geological history of Borneo

The base of rocks that underlie Borneo, an island in Southeast Asia, was formed by the arc-continent collisions, continent–continent collisions and subduction–accretion due to convergence between the Asian, India–Australia, and Philippine Sea-Pacific plates over the last 400 million years.[1] The active geological processes of Borneo are mild as all of the volcanoes are extinct.[2] The geological forces shaping SE Asia today are from three plate boundaries: the collisional zone in Sulawesi southeast of Borneo, the Java-Sumatra subduction boundary and the India-Eurasia continental collision.[3]

Early amalgamation from Gondwana

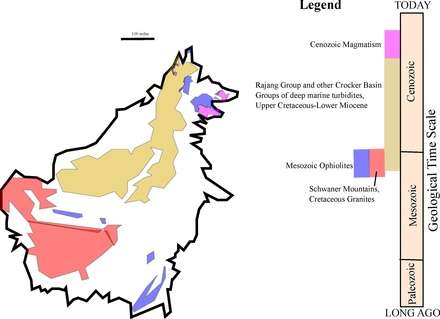

The SE Asia region is made up of fragments of crust that drifted northwards after being separated from Gondwana.[1][4] These continental fragments make up the basement that formed prior to the magmatic activity and ophiolite emplacement. Gondwana was a large continent that once extended over the south pole during the Paleozoic times. Some of these crustal fragments form Sundaland, the region of the continental core of SE Asia. Sundaland is surrounded by the South China and India continental blocks to the north and Australia to the south. Fragments of Gondwana that reached as far north as Eurasia include Thailand and peninsular Malaysia. Other fragments that did not reach so far north form southwest Borneo's Schwaner Mountains in Kalimantan, and also Sumatra and Java.[1][2][5]

The rifting, migrating northwards and accretion to form Sundaland took place during the Late Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic in three stages. The stages were controlled by the opening and closing of the Tethys Ocean separating Gondwana from Eurasia. Gondwana was in the south and Eurasia migrated north to its current location where it is relatively fixed today. These stages were during the Devonian, Late Permian and Late Triassic.[1]

In addition to a basement of crustal fragments rifted from Gondwana, SE Asia is also characterised by:

- Mesozoic ophiolite emplacement across much of SE Asia due to the subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific plate.

- A prolonged period of magmatism across much of SE Asia that formed extrusions and intrusions into the basement ophiolites and crustal blocks.[5]

- Sedimentation that dominated through the Late Mesozoic across the region following the end of the subduction.[6]

- Cenozoic extension and Rifting of the South China Sea to the north of Borneo during the Eocene where multiple models have been suggested to accommodate this spreading.[2]

Mesozoic subduction

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous time periods there was extensive volcanism and intrusions caused by the subduction of an oceanic plate. The western Pacific plate was subducted beneath SE China and SE Asia. The initiation of this subduction caused ophiolites to be emplaced and the development of the Pacific arc, a magmatic belt across SE Asia. Ophiolites are large blocks of oceanic crust that have been thrust onto continental crust due to compression that forms subduction type collisional plate boundaries.[6]

The early Pacific arc is a curved line of volcanism and intrusions where the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean subducted beneath Borneo, Vietnam and South China. The resulting long period of magmatism is evident from intrusions and extrusions reaching as far north as South China, through Hong Kong, the South China Sea continental shelf, Vietnam and to Kalimantan in southwest Borneo. This period of magmatism continued until 79Ma, when the margin moved east.[6] The ages of magmatism in these locations are 186 Ma to 76 Ma for the Schwaner Mountains granites of Kalimantan; at 180 Ma to 79 Ma in South China; at 165 Ma to 140 Ma in Hong Kong and at 112 Ma to 88 Ma in Dalat in Vietnam.[6] The magmatic belt of arc granites and volcanism across SE Asia produced by this subduction was hundreds of kilometres wide, with a total area of 220,000 km2.[6]

Ophiolite emplacement

There are many crustal fragments in northeast Borneo that are derived from Mesozoic ophiolites placed during the initiation of the western Pacific Ocean plate subducting beneath southeast China and southeast Asia.[6] This ophiolite basement underlies regions from Sabah in northeast Borneo and the Meratus Mountains in southeast Borneo. The ophiolite crustal fragments were also emplaced in Central Java to the south of Borneo and Palawan and the Philippines in the North.[6]

An ophiolite is a sequence of oceanic lithosphere that has been thrust on top of continental lithosphere and therefore has peridotites, gabbros and basaltic units overlain by cherts and submarine volcanic and sedimentary rocks.[6] Ophiolites originate as oceanic crust, they are ultramafic or mafic in composition and have a high concentration of pyroxene and amphibole minerals. Surface exposures of the ophiolite basement can be seen in the Segama Valley, Darvel Bay, Telupid and Kudat.[6] K-Ar dating of the ophiolites has indicated that they are Cretaceous in age supporting subduction beneath Borneo at this time.[5]

Late Cretaceous – Cenozoic sedimentation

Sedimentation took place after the ophiolite emplacement and magmatism of the South China Sea related to the Mesozoic western Pacific subduction. The sedimentation shows transition from deep marine mudstones and turbidites in the Paleogene to shallow marine sandstones, deltaic fluvial and carbonates during the Miocene and into the Pliocene. This gives evidence supporting changes to the environmental setting that occurred due to rifting, uplift and sedimentation events. The Rajang Group and Kinabatangan Group are characterised by the deep marine sediments while the Serudong Group is made up of sediments deposited in a shallower marine environment.[6]

A prolonged period of extension of the South China Sea took place during the Late Cretaceous to Miocene.[7] The cause of the northwest-southeast spreading of the South China Sea is not yet defined however there are various potential models that represent different kinematic processes.[5] Looking at the sedimentary record can help constrain this period of extension and its causes. An account of the late Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentation follows.

Rajang Group

Sedimentation took place predominantly during the Early Tertiary in the Crocker Basin which is found today in the northwest of Borneo and off the present-day coast. Deep marine turbidites and mudstones known as the Rajang Group were deposited.[6] Deposition is thought to coincide in time with when India began colliding with Asia.[2] Within the Rajang Group sedimentary record, the end of the South China Sea spreading is recorded showing a transition from active continental margin in the Late Cretaceous to a deep marine setting through the Tertiary.[4][6] The Rajang Group has subsequently undergone strong deformation and been uplifted to its current 1 km elevation to form the Interior Highlands of Borneo.[2][8]

Kinabatangan Group

In the Late Eocene, above the Rajang Group, there is a period of no deposition, marking the tectonic uplift event of the Sarawak Orogeny.[3] This period of time with no deposition is called an unconformity and appears as a gap in time in the sedimentary record. Following this, Oligocene deposition of the Kinabatangan Group occurred, which also consisted of turbidites and marine mudstones. Turbidites and mudstones are indicative of a deep marine environment due to the low energy in deep oceans which forms the fine grained mudstones with occasional submarine landslide type events forming turbidites. The Crocker Fan, that makes up part of the Kinabatangan Group, has vast volumes of Paleogene deep marine sediment.[5] The timing of this depositional period is not constrained but evidence from recent research favours its correlation to Late Eocene.[3] The Crocker Fan has the largest volume of any Paleogene deep marine sediment in a single basin in southeast Asia.[9]

Serudong Group

The Miocene uplift in Sabah began to change sedimentary deposits from deep marine turbidites and cherts to shallowing coastal marine sediments during the Miocene and into the Pliocene.[6] The shallowing succession saw deposition of carbonates and shows a transition from marine to deltaic fluvial deposits which together form the Serudong Group.[6] This represents shallowing of the environment as deltas are coastal features found where a river meets the sea. Early Miocene sedimentation is seen in basins to the east and northeast of Borneo. The newfound space for sediments to accumulate was introduced by Eocene rifting.[6] Erosional material sourced from the Borneo highlands along with other older parts of the basin margins being uplifted

.[5] Cenozoic magmatism mentioned below that caused intrusions such as at Mt. Kinabalu could be potentially related to this regional uplift.

Cenozoic South China Sea extension

Northeast Borneo's Cenozoic tectonics are still in hot debate, where there are three models explaining the crustal extension in the north of Borneo.[5] The Proto-South China Sea plate previously lay to the east of today's Dangerous Grounds off the coast of Sabah, northwest Borneo.[2] The Dangerous Grounds is a crustal block that forms part of the South China Sea and lies to the northwest of Borneo gaining its name by sailor's description of the shoals and reefs scattered ground.[5] It is a basement of continental crust and forms the continental shelf of the South China Sea to the northwest of Sabah.[1] The spreading of the South China Sea is no longer active.

During the Eocene, extension of the Dangerous Grounds began, followed by further extension during the Oligocene.[5][10] This extension across the South China Sea was in the northwest-southeast direction and caused thinning and rifting. This led to the formation of the South China Sea basin to the northwest of the Mesozoic arc that once extended across much of SE Asia.[7] The extension that occurred formed a triangle-shaped rift area due to the kinematics of the rifting taking place like the blades of an opening pair of scissors.

The three competing models mentioned above describe this rifting and thinning during the Late Mesozoic and vary slightly between different authors. Here, the three models are illustrated as:[6]

- The extrusion model where lateral strike slip faults are projected through the South China Sea and lateral displacement caused by the India-Asia collision forces the extension

- The Subduction Model which coincides well with evidence on the formation of the Dangerous Grounds where slab pull caused extension as the Proto-South China Sea was subducted beneath NW Borneo

- The continental rift basin model where distant processes of slab roll back south of Borneo near Java and Sumatra caused magmatism leading to the crustal extension northwest of Borneo and formation of A-type granites.[6]

Extrusion model

The extrusion model links the India-Asia collision to the extension of the South China Sea. The collision would cause the lateral extension of strike slip faults in the South China Sea.[3] This is where crust is squeezed out to the sides as India barges north into the Eurasia continent. The northward movement of India pushes the southeast Asia block away from the collision resulting in the clockwise rotation of Borneo forming a large extensional basin.[7]

In defining whether this model is correct it is important to understand if the strike slip faults of south China extend through the South China Sea as far as Borneo. Three major faults are known to traverse Indochina and South China are the Three Pagodas, Mae Ping and the Red River Fault, but not where they continue off the coast. It is not confirmed how far they cut into the South China Sea.[2]

The West Baram fault runs northwest-southeast off the coast of Sarawak, Borneo and separates blocks of differing geological histories, one of which is the Dangerous Grounds to the northeast. This fault is important as the slip is thought to accommodate proposed subduction of the proto South China Sea. Therefore, the amount of displacement along the strike-slip faults in Borneo are key to understand which model is correct. Along the West Baram fault there is not extensive displacement, indicating very little passage of the proto-South China Sea and possibly no subduction. However these models cannot conclude that the lack of lateral displacement demonstrates that the Extrusion Model must be false. A narrow proto-South China Sea or other crustal deformation could potentially have accommodated the subducting proto South China Sea and account for the lack of displacement along strike-slip faults.[5]

Continental Rift Basin model

One of the three models for the thinning and rifting of the continental crust of the South China Sea is initiated by Java and Sumatra subduction causing extrusion and slab roll back along the margin. The stresses from these were experienced in the South China Sea and together they caused the southward extension of the South China Sea. This model indicates subduction to the south of Borneo near Java and Sumatra but not subduction of Borneo or beneath Borneo.[6] This is unlikely to have caused South China Sea spreading singlehandedly but probably contributed to the forces involved.

Subduction model

The subduction model proposes that the proto-South China Sea formed a subduction zone to its east, which subsequently, by the process of slab pull, subducted the proto-South China Sea beneath northwest Borneo. When the Dangerous Grounds collided with the Mesozoic granites of the Schwaner Mountains in Borneo, it brought an end to the subduction.[3][11] This is due to the less dense Dangerous Grounds not having a big enough density contrast compared to the overlying plate. Therefore, with the end to subduction a suture was formed where the proto-South China Sea ceased subduction and the crustal margins came together. The proposed suture lies beneath Mount Kinabalu in northeast Borneo.

The subduction zone is generally thought to be about 400 km to the northwest of the suture.[5] This subduction period took place throughout the Eocene and ended in the Early Miocene.[5]

Late Ceneozoic Magmatism and the Mount Kinabalu intrusion

Dating and defining the history of the Mount Kinabalu granitic intrusion faces many challenges due to the high erosion, difficult access through relief and rainforests, difficult to define boundaries and alteration. The general geology of southeast Asia during the Cenozoic is not well defined making the reconstruction of geological events leading to Borneo's current setting an interesting point of study.[11]

Mount Kinabalu is in Sabah, northeast Borneo and is 4095 m high. It was intruded at the same time as other Late Cenozoic magmatism that occurred in the South China Sea. The Mount Kinabalu intrusion is a laccolith where intrusion of magma pushes up into the stratigraphy. The sediments in the overlying stratigraphy have been deformed as a result of this pluton style intrusion. The Mount Kinabalu intrusion is a laccolith style pluton that caused the deformation of sediments overlying the intrusion. It intruded between 7.85Ma and 7.22Ma into shallow depths of less than 12 km splitting the overlying sediments from the underlying ultramafic basement rocks. Other magmatism in Borneo during the Late Cenozoic include intrusive and extrusive in Sarawak, the Semporna Volcanics of Eastern Sabah and in Kalimantan.[6]

References

- Metcalfe, I. (8 April 2013). "Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: Tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 66: 1–33. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.12.020.

- Hall, Robert; van Hattum, Marco W. A.; Spakman, Wim (28 April 2008). "Impact of India–Asia collision on SE Asia: The record in Borneo". Tectonophysics. Asia out of Tethys: Geochronologic, Tectonic and Sedimentary Records. 451 (1–4): 366–389. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2007.11.058.

- Pubellier, M.; Morley, C. K. (1 December 2014). "The basins of Sundaland (SE Asia): Evolution and boundary conditions". Marine and Petroleum Geology. Evolution, Structure, and Sedimentary Record of the South China Sea and Adjacent Basins. 58, Part B: 555–578. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2013.11.019.

- White, L. T.; Graham, I.; Tanner, D.; Hall, R.; Armstrong, R. A.; Yaxley, G.; Barron, L.; Spencer, L.; van Leeuwen, T. M. (1 October 2016). "The provenance of Borneo's enigmatic alluvial diamonds: A case study from Cempaka, SE Kalimantan". Gondwana Research. 38: 251–272. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2015.12.007.

- Cullen, Andrew (1 March 2014). "Nature and significance of the West Baram and Tinjar Lines, NW Borneo". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 51: 197–209. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2013.11.010.

- A. Burton-Johnson (2013). Origin, emplacement and tectonic relevance of the Mt. Kinabalu granitic pluton of Sabah, Borneo. Durham University (Thesis). Durham theses. pp. 1–296.

- Morley, C. K. (1 October 2012). "Late Cretaceous–Early Palaeogene tectonic development of SE Asia". Earth-Science Reviews. 115 (1–2): 37–75. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.08.002.

- Mathew, Manoj Joseph; Menier, David; Siddiqui, Numair; Kumar, Shashi Gaurav; Authemayou, Christine (15 August 2016). "Active tectonic deformation along rejuvenated faults in tropical Borneo: Inferences obtained from tectono-geomorphic evaluation". Geomorphology. 267: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.05.016.

- van Hattum, Marco W.A.; Hall, Robert; Pickard, April L.; Nichols, Gary J. (2006). "Southeast Asian sediments not from Asia: Provenance and geochronology of north Borneo sandstones". Geology. 34 (7): 589. doi:10.1130/G21939.1.

- Lambiase, Joseph J.; Cullen, Andrew B. (25 October 2013). "Sediment supply systems of the Champion "Delta" of NW Borneo: Implications for deepwater reservoir sandstones". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 76: 356–371. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.12.004.

- Madon, Mazlan; Kim, Cheng Ly; Wong, Robert (25 October 2013). "The structure and stratigraphy of deepwater Sarawak, Malaysia: Implications for tectonic evolution". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 76: 312–333. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2013.04.040.