Galactic tide

A galactic tide is a tidal force experienced by objects subject to the gravitational field of a galaxy such as the Milky Way. Particular areas of interest concerning galactic tides include galactic collisions, the disruption of dwarf or satellite galaxies, and the Milky Way's tidal effect on the Oort cloud of the Solar System.

Effects on external galaxies

Galaxy collisions

Tidal forces are dependent on the gradient of a gravitational field, rather than its strength, and so tidal effects are usually limited to the immediate surroundings of a galaxy. Two large galaxies undergoing collisions or passing nearby each other will be subjected to very large tidal forces, often producing the most visually striking demonstrations of galactic tides in action.

Two interacting galaxies will rarely (if ever) collide head-on, and the tidal forces will distort each galaxy along an axis pointing roughly towards and away from its perturber. As the two galaxies briefly orbit each other, these distorted regions, which are pulled away from the main body of each galaxy, will be sheared by the galaxy's differential rotation and flung off into intergalactic space, forming tidal tails. Such tails are typically strongly curved. If a tail appears to be straight, it is probably being viewed edge-on. The stars and gas that comprise the tails will have been pulled from the easily distorted galactic discs (or other extremities) of one or both bodies, rather than the gravitationally bound galactic centres.[1] Two very prominent examples of collisions producing tidal tails are the Mice Galaxies and the Antennae Galaxies.

Just as the Moon raises two water tides on opposite sides of the Earth, so a galactic tide produces two arms in its galactic companion. While a large tail is formed if the perturbed galaxy is equal to or less massive than its partner, if it is significantly more massive than the perturbing galaxy, then the trailing arm will be relatively minor, and the leading arm, sometimes called a bridge, will be more prominent.[1] Tidal bridges are typically harder to distinguish than tidal tails: in the first instance, the bridge may be absorbed by the passing galaxy or the resulting merged galaxy, making it visible for a shorter duration than a typical large tail. Secondly, if one of the two galaxies is in the foreground, then the second galaxy — and the bridge between them — may be partially obscured. Together, these effects can make it hard to see where one galaxy ends and the next begins. Tidal loops, where a tail joins with its parent galaxy at both ends, are rarer still.[2]

Satellite interactions

Because tidal effects are strongest in the immediate vicinity of a galaxy, satellite galaxies are particularly likely to be affected. Such an external force upon a satellite can produce ordered motions within it, leading to large-scale observable effects: the interior structure and motions of a dwarf satellite galaxy may be severely affected by a galactic tide, inducing rotation (as with the tides of the Earth's oceans) or an anomalous mass-to-luminosity ratio.[3] Satellite galaxies can also be subjected to the same tidal stripping that occurs in galactic collisions, where stars and gas are torn from the extremities of a galaxy, possibly to be absorbed by its companion. The dwarf galaxy M32, a satellite galaxy of Andromeda, may have lost its spiral arms to tidal stripping, while a high star formation rate in the remaining core may be the result of tidally-induced motions of the remaining molecular clouds[4] (Because tidal forces can knead and compress the interstellar gas clouds inside galaxies, they induce large amounts of star formation in small satellites.)

The stripping mechanism is the same as between two comparable galaxies, although its comparatively weak gravitational field ensures that only the satellite, not the host galaxy, is affected. If the satellite is very small compared to the host, the tidal debris tails produced are likely to be symmetric, and follow a very similar orbit, effectively tracing the satellite's path.[5] However, if the satellite is reasonably large—typically over one ten thousandth the mass of its host—then the satellite's own gravity may affect the tails, breaking the symmetry and accelerating the tails in different directions. The resulting structure is dependent on both the mass and orbit of the satellite, and the mass and structure of the conjectured galactic halo around the host, and may provide a means of probing the dark matter potential of a galaxy such as the Milky Way.[6]

Over many orbits of its parent galaxy, or if the orbit passes too close to it, a dwarf satellite may eventually be completely disrupted, to form a tidal stream of stars and gas wrapping around the larger body. It has been suggested that the extended discs of gas and stars around some galaxies, such as Andromeda, may be the result of the complete tidal disruption (and subsequent merger with the parent galaxy) of a dwarf satellite galaxy.[7]

Effects on bodies within a galaxy

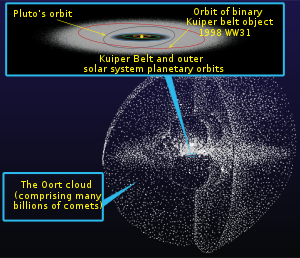

Tidal effects are also present within a galaxy, where their gradients are likely to be steepest. This can have consequences for the formation of stars and planetary systems. Typically a star's gravity will dominate within its own system, with only the passage of other stars substantially affecting dynamics. However, at the outer reaches of the system, the star's gravity is weak and galactic tides may be significant. In the Solar System, the hypothetical Oort cloud, believed to be the source of long-period comets, lies in this transitional region.

The Oort cloud is believed to be a vast shell surrounding the Solar System, possibly over a light-year in radius. Across such a vast distance, the gradient of the Milky Way's gravitational field plays a far more noticeable role. Because of this gradient, galactic tides may then deform an otherwise spherical Oort cloud, stretching the cloud in the direction of the galactic centre and compressing it along the other two axes, just as the Earth distends in response to the gravity of the Moon.

The Sun's gravity is sufficiently weak at such a distance that these small galactic perturbations may be enough to dislodge some planetesimals from such distant orbits, sending them towards the Sun and planets by significantly reducing their perihelia.[8] Such a body, being composed of a rock and ice mixture, would become a comet when subjected to the increased solar radiation present in the inner Solar System.

It has been suggested that the galactic tide may also contribute to the formation of an Oort cloud, by increasing the perihelia of planetesimals with large aphelia.[9] This shows that the effects of the galactic tide are quite complex, and depend heavily on the behaviour of individual objects within a planetary system. However, cumulatively, the effect can be quite significant; up to 90% of all comets originating from an Oort cloud may be the result of the galactic tide.[10]

References

- Toomre A.; Toomre J. (1972). "Galactic Bridges and Tails". The Astrophysical Journal. 178: 623–666. Bibcode:1972ApJ...178..623T. doi:10.1086/151823.

- Wehner E.H.; et al. (2006). "NGC 3310 and its tidal debris: remnants of galaxy evolution". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371 (3): 1047–1056. arXiv:astro-ph/0607088. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.371.1047W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10757.x.

- Piatek S.; Pryor C. (1993). "Can Galactic Tides Inflate the Apparent M/L's of Dwarf Galaxies?". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 25: 1383. Bibcode:1993AAS...183.5701P.

- Bekki, Kenji; Couch, Warrick J.; Drinkwater, Michael J.; Gregg, Michael D. (2001). "A New Formation Model for M32: A Threshed Early-Type Spiral Galaxy?" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 557 (1): Issue 1, pp. L39–L42. arXiv:astro-ph/0107117. Bibcode:2001ApJ...557L..39B. doi:10.1086/323075.

- Johnston, K.V.; Hernquist, L.; Bolte, M. (1996). "Fossil Signatures of Ancient Accretion Events in the Halo". The Astrophysical Journal. 465: 278. arXiv:astro-ph/9602060. Bibcode:1996ApJ...465..278J. doi:10.1086/177418.

- Choi, J.-H.; Weinberg, M.D.; Katz, N. (2007). "The dynamics of tidal tails from massive satellites". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 381 (3): 987–1000. arXiv:astro-ph/0702353. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.381..987C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12313.x.

- Peñarrubia J.; McConnachie A.; Babul A. (2006). "On the Formation of Extended Galactic Disks by Tidally Disrupted Dwarf Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 650 (1): L33–L36. arXiv:astro-ph/0606101. Bibcode:2006ApJ...650L..33P. doi:10.1086/508656.

- Fouchard M.; et al. (2006). "Long-term effects of the Galactic tide on cometary dynamics". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 95 (1–4): 299–326. Bibcode:2006CeMDA..95..299F. doi:10.1007/s10569-006-9027-8.

- Higuchi A., Kokubo E.; Mukai, T. (2005). "Orbital Evolution of Planetesimals by the Galactic Tide". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 37: 521. Bibcode:2005DDA....36.0205H.

- Nurmi P.; Valtonen M.J.; Zheng J.Q. (2001). "Periodic variation of Oort Cloud flux and cometary impacts on the Earth and Jupiter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 327 (4): 1367–1376. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.327.1367N. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04854.x.