Gaius Valerius Troucillus

Gaius Valerius Troucillus or Procillus[1] (fl. mid-1st century BC) was a Helvian Celt who served as an interpreter and envoy for Julius Caesar in the first year of the Gallic Wars. Troucillus was a second-generation Roman citizen, and is one of the few ethnic Celts who can be identified both as a citizen and by affiliation with a Celtic polity. His father, Caburus, and a brother are named in Book 7 of Caesar's Bellum Gallicum as defenders of Helvian territory against a force sent by Vercingetorix in 52 BC. Troucillus plays a role in two episodes from the first book of Caesar's war commentaries (58 BC), as an interpreter for the druid Diviciacus and as an envoy to the Suebian king Ariovistus, who accuses him of spying and has him thrown in chains.

Troucillus was an exact contemporary of two other notable Transalpine Gauls: the Vocontian father of the historian Pompeius Trogus, who was a high-level administrator on Caesar's staff; and Varro Atacinus, the earliest Transalpiner to acquire a literary reputation in Rome as a Latin poet. Their ability as well-educated men to rise in Roman society is evidence of early Gallo-Roman acculturation.[2]

Two names, one man?

Caesar first mentions Valerius Troucillus in Bellum Gallicum 1.19, when the Roman commander is made aware of questionable loyalties among the Celtic Aedui, Rome's allies in central Gaul since at least the 120s BC. Caesar represents this divided allegiance in the persons of two brothers, the druid Diviciacus, who had appeared before the Roman senate a few years earlier to request aid against Germanic invaders, and the enterprising populist Dumnorix, who was the leading Aeduan in terms of wealth and military power.[3] Dumnorix stood accused of conspiring with the enemy Helvetii; when Caesar holds a confidential discussion with his friend Diviciacus, he dismisses the usual interpreters[4] and calls in Troucillus. Caesar describes Troucillus as a leading citizen of the province of Gallia Narbonensis and his personal friend (familiaris),[5] adding that he placed the highest trust (fides) in the Helvian in all matters.[6]

At Bellum Gallicum 1.46 and 52, Caesar names a Transalpine Gaul, this time according to the manuscripts as Gaius Valerius Procillus, whom he again calls his familiaris as well as his hospes. The hospes, sometimes translatable as a "family friend" and meaning "guest" or "host" in Latin interchangeably, is a participant in the mutual social relationship of hospitium, reciprocal guest-host hospitality. Caesar's use of the term may imply that he was a guest of the Helvian Valerii when he traveled through the Narbonensis, as he did to or from one of his two postings in Hispania during the 60s, or that the Helvian had been a guest of Caesar in Rome before the war.[7] Most scholars[8] assume that the two names refer to a single man; although Troucillus is a problematic reading of the text, it is a well-established Celtic name,[9] whereas Procillus appears to have been confused with a Roman name.[10] In this episode, Caesar sends Troucillus as a diplomatic envoy to the Suebian king Ariovistus,[11] and again commends his linguistic skills and his fides, his loyalty or trustworthiness.

Caesar identifies Troucillus as an adulescens, a young man, generally in Caesarian usage between the ages of 20 and 30 and not having yet entered the political career track or held a formal command. The term is used elsewhere in the Bellum Gallicum for Publius Crassus[12] and Decimus Brutus,[13] who were born in the mid-80s.[14]

Princeps and legate

Caesar's identification of Troucillus's citizen status provides a piece of evidence for the history of Roman provincial administration in Gaul. Caesar notes that he is the son of Gaius Valerius Caburus, who was granted citizenship by G. Valerius Flaccus during his governorship in the 80s. Caburus took his patron's gentilic name, as was customary for naturalized citizens. Although Caburus's two sons retain a Celtic cognomen (personal name), by the third generation a member of such a family is likely to be using a more typically Roman name, and the Helvian Valerii cannot be identified further in the historical record.[15]

The reference to Caburus's grant of citizenship in 83 BC helps date the term of Flaccus in his Transalpine province, and shows that Gauls were receiving Roman citizenship soon after annexation.[16] As indicated by his closeness in age to Crassus and Brutus, Troucillus was born shortly before or after his father became a citizen, and was among the first Transalpiners to grow up with a dual Gallo-Roman identity.

Although no title or rank is given for Troucillus, Caesar calls him a princeps Galliae provinciae, "a leading citizen of the Province of Gaul". His father, Caburus, is called princeps civitatis[17] of the Helvii, who are identified in this phrase not as a pagus, much less a "tribe" (Latin tribus), but as a civitas, a polity with at least small-scale urban centers (oppida).[18] It has been argued that princeps denotes a particular office in the Narbonensis,[19] but the word is usually taken to mean simply a "leader" or "leading citizen." Troucillus is listed among legates and envoys for 58 BC in Broughton's Magistrates of the Roman Republic.[20] Erich S. Gruen notes the presence of Troucillus among those who demonstrate that Caesar favored men of non-Roman and equestrian origin among his junior officers and lieutenants.[21] Ronald Syme calls the Helvian "a cultivated and admirable young man."[22]

Troucillus was accompanied on the mission to Ariovistus by Marcus Mettius (or Metius), a Roman who had a formal social relationship (hospitium) with the Suebian king. Since Ariovistus had been declared a Friend of the Roman People (amicus populi romani) during Caesar's consulship in 59 BC, the hospitium between him and Mettius might have had to do with the diplomacy that led to the declaration of friendship;[23] business dealings involving goods, slaves, or animals are also not out of the question.[24] In 60 BC, the senate had sent three legates on a diplomatic mission to shore up relations to key Gallic civitates, including the Aedui, against the threatened invasion or inducements of the Helvetii, whose entry into Allobrogian and Aeduan territory two years later provided Caesar with a casus belli. One of these legates was Lucius Valerius Flaccus, the nephew of the Valerius Flaccus who had granted Caburus's citizenship.[25] Lucius had served under his uncle in the Narbonensis at the beginning of his career.[26] Because of their ties to the Valerii Flacci, Troucillus or another member of his family might have traveled with Flaccus as interpreter or liaison. Caesar explains his decision to send Troucillus to Ariovistus on linguistic grounds, saying that the Suebian king had learned to speak Celtic.[27]

Despite Caesar's assertion that the king should have no cause to find fault with Troucillus, Ariovistus immediately accuses the pair of envoys of spying and refuses to allow them to speak. He has Troucillus thrown in chains. Such treatment of envoys was a violation of the ius gentium, the customary law of international relations,[28] but it has been observed that Ariovistus's charge may not have been groundless.[29]

Troucillus is held by the Suebi until the decisive battle, in which the Romans are victorious. Caesar gives the recovery of the young Celt an emphatic place in the penultimate paragraph of the book; several scholars[30] have detected a degree of personal warmth in the passage that is atypical of the commentaries:

Caesar himself, while pursuing the enemy with his cavalry, happened upon C. Valerius Troucillus,[31] bound in three chains and dragged along by guards during the rout. This event indeed brought Caesar a pleasure no less than the victory itself, because he saw the most worthy man of the Gallic province, both a personal and a social friend,[32] snatched from the hands of the enemy and restored to him; fortune had not diminished any element of pleasure or thanksgiving by his loss.[33] Troucillus told how three times, before his very eyes, they had cast lots to determine whether he should be burnt alive on the spot or whether to put it off for another time; thanks to the luck of the draw, he was unharmed. Marcus Metius likewise was recovered and brought to Caesar.[34]

In his discussion of racial stereotyping among the Romans, A.N. Sherwin-White takes note of this passage in Caesar's overall depiction of Ariovistus as "an impossible person" who thought "nothing of frying an envoy."[35] For reasons that are unclear, the Roman Mettius seems to have received better treatment during his captivity than did the Celtic envoy.[36] The episode allows Caesar himself to display by contrast the aristocratic virtue of treating one's dependent friends well, which fosters obligations that enhance the important man's prestige.[37]

Religious significance

H.R. Ellis Davidson views the casting of lots and proposed immolation of Troucillus as a form of human sacrifice in the context of Germanic religious practice.[38] Both Celtic and Germanic peoples were said to practice human sacrifice, and it had been banned from Roman religious use by law only about forty years before the Gallic War.[39] In his ethnography Germania, Tacitus notes that divination by means of lots was pervasive among the Germans,[40] and records a rite of human sacrifice among the Semnones, "the most ancient and noble of the Suebi," that involves binding the participant in a chain; in his edition, J.B. Rives connects the practice to the incident involving Troucillus.[41] Tacitus describes the use of twigs with markings in the casting of lots, and it has been suggested that these were used to cast the lots for Troucillus, with the markings an early form of runes.[42] An 8th-century source says that the Germanic Frisians cast lots over a period of three days to determine the death penalty in cases of sacrilege,[43] and the lots were cast three times for Troucillus; spying in the guise of diplomatic envoy would violate the sacred trust under the aegis of hospitium.

The Helvii and Roman politics

No polity within Caesar's Narbonese province joined the pan-Gallic rebellion of 52 BC, nor engaged in any known acts of hostility against Rome during the war. The family of Troucillus, in fact, plays a key role in securing Caesar's rear militarily against Vercingetorix, who sent forces to invade Helvian territory. In his 1861 history of the Vivarais,[44] Abbé Rouchier conjectured that Caesar, seeing the strategic utility of Helvian territory on the border of the Roman province along a main route into central Gaul, was able to cultivate the Valerii by redressing punitive measures taken against the civitas by Pompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great") in the 70s. During the secession of Quintus Sertorius in Spain, Celtic polities in Mediterranean Gaul were subjected to troop levies and forced requisitions to support the military efforts of Metellus Pius, Pompeius, and other Roman commanders against the rebels. Some Celts, however, supported Sertorius. After the renegade Roman was assassinated, Metellus and Pompeius were able to declare a victory, and the Helvii along with the Volcae Arecomici were forced to cede a portion of their lands to the Greek city-state Massilia (present-day Marseilles), a loyal independent ally of Rome for centuries, located strategically at the mouth of the Rhône. Caesar mentions the land forfeiture in his account of the civil war, without detailing Helvian actions against Rome.[45] During the Roman civil wars of the 40s, Massilia chose to maintain its longstanding relationship with Pompeius even in isolation, as the Gallic polities of the Narbonensis continued to support Caesar.[46] The Massiliots were besieged and defeated by Caesar, and as a result lost their independence, as well as possibly the land they had taken from the Helvii. Rouchier presents an extended portrait of Troucillus in his history, viewing the educated young Celt through Caesar's eyes as an example of a visionary meritocracy in Rome.[47]

Humanitas, virtus and becoming Roman

During his dictatorship, Caesar extended full rights of Roman citizenship to ethnically Celtic Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), and filled the roll of the Roman senate with controversial appointments that included Cisalpine and possibly a few Narbonese Gauls. Although accusations of degrading the senate with uncivilized "trouser-wearing Gauls"[48] were exaggerations meant to disparage Caesar's inclusive efforts, Ronald Syme has pointed out that men such as Troucillus and Trogus were educated citizens worthy of such appointments:

Gallia Narbonensis can assert a peculiar and proper claim to be the home of trousered senators. No names are recorded. Yet surmise about origins and social standing may claim validity. The province could boast opulent and cultivated natives of dynastic families, Hellenized before they became Roman, whose citizenship, so far from being the recent gift of Caesar, went back to proconsuls a generation or two earlier.[49]

Troucillus's fluent bilingualism is asserted by Caesar. The French scholar Christian Goudineau found it "perplexing" to have Caesar take special note that a native Gaul spoke Gaulish, and suggests that this emphasis on Troucillus's retention of what should have been his first language indicates that the Helvian had been given the same education as a Roman, perhaps even in Rome and maybe as a hostage.[50]

Syme points out that the Gauls of the Provincia had direct exposure to the Greek language and to Hellenic culture through the regional influence of Massilia,[51] which had well-established contact with the Helvii (see "The Helvii and Roman politics" above). The cultural and linguistic complexity of Mediterranean Gaul is asserted by Varro, who says Massilia is "trilingual, because they speak Greek, Latin, and Gaulish."[52]

Caesar employs two abstract nouns from the Roman moral vocabulary to describe Troucillus: he is said to be outstanding for his humanitas and his virtus.[53] Humanitas was "a keyword for late Republican elite self-definition";[54] it embraced a range of ideals including culture, civilization, education, and goodwill toward one's fellow human beings. Cicero considered humanitas to be one of Caesar's own outstanding qualities,[55] and often pairs it with lepos, "charm"; in his speech arguing for the extension of Caesar's proconsular command, he distinguishes Roman culture from Gallic by mockingly asking whether "the culture and charm of those people and nations" could possibly be the attraction for Caesar, rather than the war's usefulness to the state (utilitas rei publicae).[56] Cicero also associates humanitas with speaking well, the ability to hold a cultivated conversation free of vulgarity and to speak in an urbane manner.[57]

A hundred and fifty years later, Tacitus takes a more cynical view of humanitas as an illusion of civilization that is in fact submission to the dominant culture.[58] Tacitus observes that as governor of Roman Britain, Agricola had engaged in a program of

edifying the sons of chieftains by means of the liberal arts and promoting the natural abilities of the Britons over the intellectual achievements of the Gauls,[59] so that now those who used to shun the Roman tongue craved eloquence. After that it was considered an honor to dress like us, and togas were everywhere. Little by little resistance melted in contact with vices — covered walkways and hot baths and fashionable dinner parties. And among the benighted this was called civilization (humanitas), although it was an aspect of slavery.[60]

The Roman concept of humanitas as it took shape in the 1st century BC has been criticized from a postcolonial perspective as a form of imperialism, "a civilizing mission: it was Rome's destiny and duty to spread humanitas to other races, tempering barbarian practices and instituting the pax Romana."[61]

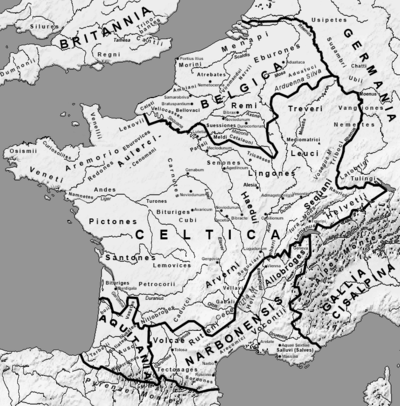

The word humanitas appears only twice throughout the entirety of Caesar's Bellum Gallicum, both times in Book 1. In the famous opening, in which the commander parcels out Gaul into three divisions (Belgae ... Aquitani ... Celtae, 1.1.1) for potential conquest, Caesar reports that the Belgic Gauls are the bravest (fortissimi) fighters, "because they are at the farthest remove from the cultivation (cultus) and civilization (humanitas) of the Province."[62] By contrast, Troucillus is said to possess the highest level of both humanitas and virtus.[63] Virtus, which shares a semantic element with the Latin word vir, "man,"[64] is most commonly translated by either "virtue" or "courage, valor"; it is "the quality of manliness or manhood."[65] As an active quality, appropriate to the man of action,[66] virtus balances the potentially enervating effects of civilization in the natural aristocrat.[67] Caesar's prolific use of the word virtus — fourteen instances in Book 1 alone, in reference to Celtic nations as a whole,[68] and to the Roman army[69] — points to "no easily articulated essential meaning": "Virtus was whatever it was that Romans liked when they saw it."[70] Although the word appears frequently throughout the Bellum Gallicum, Caesar attributes the quality of virtus to only a few individuals: Troucillus; three Roman officers;[71] and two Celts, Commius of the Atrebates and Tasgetius of the Carnutes.[72]

The Bellum Gallicum audience

T.P. Wiseman saw the role of Troucillus in Bellum Gallicum 1 as one indication of the breadth of Caesar's intended audience. Wiseman argues that the commentaries were first published serially,[73] with a year-by-year account to keep Caesar and his achievements vivid in the mind of the public (populus) on whose support he counted as a popularist leader. The seven individual books were then collected and supplemented by Aulus Hirtius at the end of the 50s or beginning of the 40s. "Publication" in ancient Rome relied less on the circulation of written copies than on public and private readings, which were an important form of entertainment; this circumstance, Wiseman intuits, goes a long way toward explaining Caesar's narrative use of the third person in regard to himself, since the audience would be hearing the words spoken by a reader. In addition to public relations efforts among the Roman people, Wiseman believes that Caesar would have sent readers to the Narbonensis, the Mediterranean region of Gaul already under Roman administration, because he required Narbonese support at his back if he was to succeed in independent Gaul.

The prominent attention given to the recovery of Troucillus from the Suebi at the end of Book 1, and the unusual warmth with which Caesar speaks of him, suggests that the proconsul valued his friends to the south and was careful to show it.[74] In another indication of Narbonese regard for Caesar, the poet Varro Atacinus,[75] the contemporary of Troucillus, wrote an epic poem called the Bellum Sequanicum (Sequanian War), no longer extant, about the first year of Caesar's war in Gaul.[76]

Further reading

- Christian Goudineau, "A propos de C. Valerius Procillus, un prince helvien qui parlait ... gaulois," Études celtique 26 (1989) 61–62.

References

- See discussion of name under One man, two names.

- Ronald Syme, "The Origin of Cornelius Gallus," Classical Quarterly 32 (1938) 39–44, especially p. 41. Syme's article, which is not the last word on the subject (see Cornelius Gallus), considers whether Gallus himself might be the best example of the cultured Narbonese Gaul: "If the foregoing argument is correct," he concludes, "Gallus was not of colonia Roman or of freedman stock, but, like Caesar's friends Trogus and Procillus (= Troucillus), the son of a local dynast of Gallia Narbonensis" (p. 43).

- Jonathan Barlow, “Noble Gauls and Their Other in Caesar’s Propaganda,” in Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter: The War Commentaries as Political Instruments, edited by Kathryn Welch and Anton Powell (Classical Press of Wales, 1998), pp. 139–170; Serge Lewuillon, "Histoire, société et lutte des classes en Gaule: Une féodalité à la fin de la république et au début de l'empire," Aufstieg under Niedergang der römische Welt (1975) 425–485.

- Cotidianis interpretibus remotis.

- The word amicus can mean a political friend or a socially useful friend, but familiaris implies intimacy.

- Cui summam omnium rerum fidem habebat. Latin fides represents a complex of meanings rendered variously in English as "trust," "confidence," "trustworthiness," "credibility," "fidelity," and "loyalty."

- Christian Goudineau, César et la Gaule (Paris: Errance, 1990), p. 74.

- T. Rice Holmes reviews the 19th-century scholarship in his classic work Caesar's Conquest of Gaul (London, 1903), p. 170 online. Holmes holds with the single-man identification, as do Ramsey MacMullen (who also cites a two-men argument), Romanization in the Time of Augustus, pp. 166–167, note 48, limited preview online, though he calls this man "Procillus"; and John C. Rolfe, "Did Liscus Speak Latin? Notes on Caesar B.G. i. 18. 4–6 and on the Use of Interpreters," Classical Journal 7 (1911), p. 128 online; and Ronald Syme (discussed passim in this article). See also C.-J. Guyonvarc'h, “La langue gauloise dans le De bello gallico,” Revue du CRBC 6: La Bretagne linguistique (1990), discussed at L'Arbre Celtique, "Les personnages Celtes," Troucillus/Procillus.

- D. Ellis Evans, Gaulish Personal Names (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), p. 380; Xavier Delamarre, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (Éditions Errance, 2003), p. 303, giving a derivation from trougo-, trouget-, "sad, unhappy, miserable." The name Troucillus also appears in inscriptions.

- In discussing the importation of the Roman system of three names into Gaul, the 19th-century Celticist Arbois de Jubainville accepted the name Procillus as correct and derives it from Latin procus, like the gentilic Procilius; see Recherches sur l'origine de la propriété foncière et des noms de lieux habités en France (Paris, 1890), p. 131 online. Procillus is also one of the names in the epigrams of Martial (Epigrams, book 1, poems 27 and 115), who was a Celtiberian.

- A mission referred to also by Appian, Celtic Wars 17, where Troucillus is not identified by name.

- Bellum Gallicum 1.51.7; 3.7.2 and 21.1.

- Bellum Gallicum 3.11.5; 7.9.1 and 87.1.

- Guyonvarc'h, "La langue gauloise dans le De Bello Gallico"; Elizabeth Rawson, “Crassorum funera,” Latomus 41 (1982), p. 545 on the meaning of adulescens. See further discussion at Publius Licinius Crassus: Early military career. Vercingetorix is called adulescens at BG 7.4, as is the Aeduan Convictolitavis at 7.32.4, who was one of two candidates in the disputed election for 52 BC. The Aeduan co-commanders at Alesia, Eporedorix and Viridomarus, are described as adulescentes (7.39.1 and 63.9).

- MacMullen, Romanization p. 99 online.

- Although Gallia Transalpina was brought under Roman control as a result of wars concluded in 120 BC, and the Roman colonia at Narbonne was established in 118, there is little evidence that the Narbonensis was regularly administered as a province till the 90s. Valerius Flaccus, a highly experienced administrator, had held one of the longest terms in the province until Caesar's proconsulship; see T. Corey Brennan, The Praetorship in the Roman Republic (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 363 online.

- Bellum Gallicum 7.65.2.

- John Koch notes that the Gallo-Brittonic word corresponding to Caesar's usage of civitas is most likely *touta (Old Irish túath): "'tribe' would not be a perfect translation, but is less misleading than 'state,' 'city,' or 'nation'" Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2000), p. 450 online. John Drinkwater, however, argues in Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC–AD 260 (Cornell University Press, 1983), for "'nation' in the American Indian sense (made up of a number of tribes — Caesar's pagi" (p. 30, note 2; concept of civitas discussed in depth pp. 103–111). See also A.N. Sherwin-White on civitas, populus, municipium and oppidum in The Roman Citizenship (Oxford University Press, 1973) passim; if *touta is correctly translated as "a people," the sense of civitas Helviorum might be analogous to that of the Roman People (populus) as a political entity. In his edition of Tacitus' Germania (Oxford University Press, 1999), J.B. Rives, drawing on Cicero's definition of civitas as "an assembly and gathering of men associated under law" (Republic 6.13), says that it is the usual word for a "community viewed under its political aspect," equivalent to the Greek polis (p. 153). Further discussion by Olivier Büchsenschütz, "The Significance of Major Settlements in European Iron Age Society," in Celtic Chiefdom, Celtic State (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 53–64; consideration of the term "proto-state" by Patrice Brun, "From Chiefdom to State Organization," in Celtic Chiefdom, Celtic State p. 7; see also Greg Woolf, "Urbanizing the Gauls," in Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 106–141. In Gods, Temples, and Ritual Practices: The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul (Amsterdam University Press, 1998), Ton Derks views the civitates of the Augustan era as "city-states": "a civitas was a community, whose constitution was shaped after the Roman example and whose social and political life was centred on a single town" (p. 39 online).

- Laurent Lamoine, "Préteur, vergobret, princeps en Gaule Narbonnaise et dans les Trois Gaules: pourquoi faut-il reprendre le dossier?" in Les élites et leurs facettes: Les élites locales dans le monde hellénistique et romain (École française de Rome, 2003), p. 191 online, and Le pouvoir local en Gaule romaine (Presses Universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2009), pp. 74–75 online. Christian Goudineau calls Troucillus "un prince helvien," perhaps with the assumption that his father would have been a rix (Latin rex) had the Helvii not been under Roman rule.

- T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (American Philological Association, 1952), vol. 2, p. 198.

- Erich S. Gruen, "The 'First Triumvirate' and the Reaction," in The Last Generation of the Roman Republic (University of California Press, 1974, reprinted 1995), pp. 117–118 online.

- Ronald Syme, The Origin of Cornelius Gallus," Classical Quarterly 32 (1938), p. 41, reiterated in The Roman Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1939, reissued 2002), p. 75.

- This assumption is common enough to have been noted in a student textbook for Caesar's commentaries edited by Francis W. Kelsey (Boston, 1918), p. 117 online.

- In Caesar: Life of a Colossus (Yale University Press, 2006), Adrian Goldsworthy identifies Mettius, whose praenomen he gives erroneously as Caius, as a merchant (p. 229 online). Others have made a Romanized Gaul of Mettius. None of these have a basis in the text of the Bellum Gallicum. Caesar says only that Mettius had availed himself of the hospitium of Ariovistus (qui hospitio Ariovisti utebatur, BG 1.46.4), and provides no further information about the man's social rank, ethnicity, or occupation.

- Cicero, Ad Atticum 1.19.2–3 and 20.5. The senior legate was Metellus Creticus, under whom Flaccus had served in Crete earlier in the 60s. The other man was Cn. Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus (the praetor of 59 BC, not the consul of 72).

- For more on the governorship of Flaccus and his nephew's presence in Gaul during the civil wars of the 80s, see G. Valerius Flaccus: Role in civil war.

- Commodissimum visum est C. Valerium <Troucillum> ... propter fidem et propter linguae Gallicae scientiam, qua multa iam Ariovistus longinqua consuetudine utebatur, et quod in eo peccandi Germanis causa non esset, ad eum mittere: "It seemed most advantageous to send C. Valerius Troucillus, because of his loyalty and his knowledge of the Gaulish language, in which Ariovistus had become quite fluent after his long exposure to it, and because there would be no cause for the Germans to find fault with him" (BG 1.46.4).

- Daniel Peretz, "The Roman Interpreter and His Diplomatic and Military Roles," Historia 55 (2006), p. 454.

- John H. Collins, “Caesar as Political Propagandist,” in Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 1.1 (1972), p. 930 online: "it is hard to avoid the feeling that if we had an independent report of the incident from the German side we should learn that the envoys' conduct was not quite so diplomatically correct as Caesar has represented it"; see also N.J.E. Austin and N.B. Rankov Exploratio: Military and Political Intelligence in the Roman World from the Second Punic War to the Battle of Adrianople (Routledge, 1995), p. 55.

- "Cette affection s'exprime en termes plus chaleureux" ("this affection is expressed in the warmest terms"), Ernest Desjardins, Géographie historique et administrative de la Gaule romaine (Paris, 1878), p. 512 online; the story demonstrates Caesar's "warm heart for friendship" observes Ernst Riess, reviewing a teaching text of the Bellum Gallicum in Classical Weekly 3 (1909–1910), p. 132; William Warde Fowler perceives a "genuine feeling" that "helps us to understand the secret of Caesar's wonderful influence over other men," Julius Caesar and the Foundation of the Roman Imperial System (New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892), p. 160 online; Christian Goudineau, César et la Gaule (Paris: Errance, 1990), p. 240 ("un des très rares moments de la Guerre des Gaules où César exprime une émotion"); an emotion rare in the war commentaries noted also by T.P. Wiseman, “The Publication of De Bello Gallico,” in Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter, pp. 1–9; Ronald Syme, The Provincial at Rome (University of Exeter Press, 1999), p. 64, noting the "providential delivery Caesar recounts in moving words"; and "a notable exception to Caesar's generally objective tone in his narrative," Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland, Ancient Rome from the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar (Routledge, 2005), p. 86 online.

- Most texts have Procillus at this point.

- Familiarem et hospitem.

- The sentiment as expressed by the Latin here is easy to understand, but difficult to render in nuanced English; a more natural translation based on the rhetorical emphasis of word order would be: "his loss would have deprived the occasion of some degree of happiness and cause for thanksgiving; fortune had it otherwise."

- Bellum Gallicum 1.52.5–8: C. Valerius Procillus, cum a custodibus in fuga trinis catenis vinctus traheretur, in ipsum Caesarem hostes equitatu insequentem incidit. Quae quidem res Caesari non minorem quam ipsa victoria voluptatem attulit, quod hominem honestissimum provinciae Galliae, suum familiarem et hospitem, ereptum ex manibus hostium sibi restitutum videbat neque eius calamitate de tanta voluptate et gratulatione quicquam fortuna deminuerat. Is se praesente de se ter sortibus consultum dicebat, utrum igni statim necaretur an in aliud tempus reservaretur: sortium beneficio se esse incolumem. Item M. Metius repertus et ad eum reductus est. The repetition of voluptas strikes an oddly Epicurean note, consonant with the theme of friendship; some scholars have seen an attraction to Epicureanism in Caesar, and an inordinate number of Epicureans among his supporters. See Frank C. Bourne, "Caesar the Epicurean," Classical World 70 (1977) 417–432, and Arnaldo Momigliano, review of Science and Politics in the Ancient World by Benjamin Farrington (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1939), Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941) 149–157. Miriam Griffin, "Philosophy, Politics, and Politicians at Rome," in Philosophia togata (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), observed that Caesar's camp during the Gallic Wars was a "hot-bed of Epicureanism", where Cicero's friend Trebatius Testa converted to the philosophy.

- A.N. Sherwin-White, Racial Prejudice in Imperial Rome (Cambridge University Press, 1967), pp. 14 and 17.

- Andrew Wallace-Hadrill suggests that the preexisting guest-friend connection (hospitium) between Mettius and Ariovistus accounts for this preferential treatment; see Patronage in Ancient Society (Routledge, 1989), p. 140 online.

- Steve Mason references the example of Caesar's friendship with Troucillus in Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary (Brill, 2001), p. 166, note 1718 online.

- H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions (Manchester University Press, 1988), p. 61 online.

- Banned in 97 BC during the consulship of P. Licinius Crassus, the grandfather of the Publius Crassus who served as an officer under Caesar, and Cn. Cornelius Lentulus, according to Pliny, Historia naturalis 30.3.12 (Latin text). For human sacrifice in Rome, see J.S. Reid, "Human Sacrifices at Rome and Other Notes on Roman Religion," Journal of Roman Studies 2 (1912) 34–52. A notable rite of human sacrifice in Rome was the live burial of one Greek couple and one Gallic couple in the Forum Boarium in 228 BC; see Briggs L. Twyman, "Metus Gallicus: The Celts and Roman Human Sacrifice," Ancient History Bulletin 11 (1997) 1–11; multiple instances in T.P. Wiseman, Remus (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 118 ff ("three times in the later history of the Republic the Romans resorted to human sacrifice to ward off a Gallic invasion"). Several Greek and Roman literary sources document human sacrifice among the Celts, as does archaeology, explored particularly by Jean-Louis Brunaux, for whom see: “Gallic Blood Rites,” Archaeology 54 (March/April 2001), 54–57; Les sanctuaires celtiques et leurs rapports avec le monde mediterranéean, Actes de colloque de St-Riquier (8 au 11 novembre 1990) organisés par la Direction des Antiquités de Picardie et l’UMR 126 du CNRS (Paris: Éditions Errance, 1991); “La mort du guerrier celte. Essai d’histoire des mentalités,” in Rites et espaces en pays celte et méditerranéen. Étude comparée à partir du sanctuaire d’Acy-Romance (Ardennes, France) (École française de Rome, 2000).

- The term Germani as an ethnic designation is problematic; this article takes no position on the ethnic specifics of Tacitus's referent.

- Tacitus, Germania 10 and 39; J.B. Rives (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 165 online.

- Rochus von Liliencron de:Rochus von Liliencron and Karl Müllenoff, Zur Runenlehre (Halle, 1852), pp. 29–30 and 38 online. The authors explicitly connect the casting of lots three times over Troucillus to the Frisian practice described following.

- Alcuin, Life of Willibrord 11, as cited by Giorgio Ausenda, After Empire: Towards an Ethnology of Europe's Barbarians (Boydell Press, 1995), p. 260 online.

- L'Abbé Rouchier, "L'Helvie à l'époque gauloise et sous la domination romaine," in Histoire religieuse, civile et politique du Vivarais (Paris, 1861), vol. 1, pp. 3–65, especially pp. 48–52 on Troucillus (under the name Procillus).

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili 1.35.

- Stéphane Mauné, "La centuriation de Béziers B et l'occupation du sol de la vallée de l'Hérault au Ie av. J.-C.," in Histoire, espaces et marges de l'Antiquité: Hommages à Monique Clavel Lévêque (Presses Universitaires Franc-Comtoises, 2003), vol. 2, p. 73 online.

- Noting "sa bravoure, la noblesse de son caractère, les facultés brillantes d'un esprit qui, pour parâitre supérieur, n'avait besoin que de culture": Rouchier, pp. 48–49. For Caesar's grants of citizenship and senatorial rank to Gauls, including "trousered Gauls" of Transalpina, see Humanitas, virtus and becoming Roman following.

- A jibe in poetic form is recorded by Suetonius, Divus Iulius 80.2: "Caesar led the Gauls in triumph and likewise into the senate house; the Gauls took off their trousers and put on the wide stripe" (Gallos Caesar in triumphum ducit, idem in curiam / Galli bracas deposuerunt, latum clavum sumpserunt).

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1939, reprinted 2002), p. 79; cf. "The Origins of Cornelius Gallus," p. 43.

- Christian Goudineau, César et la Gaule (Paris: Errance, 1990), p. 74. See also L'Abbé Rouchier, "L'Helvie à l'époque gauloise et sous la domination romaine," in Histoire religieuse, civile et politique du Vivarais (Paris, 1861), vol. 1, p. 88. For Roman and Celtic practices of hostage-taking in this period, see discussion of Publius Crassus's hostage crisis in Armorica in 56 BC.

- The Provincial at Rome p. 58 online.

- Varro (the famous polymath, not Varro Atacinus) as quoted by Isidore of Seville, Origines 15.1.63, trilingues quod et graece loquantur et latine et gallice; Edgar C. Polomé, "The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire," Augstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II (De Gruyter, 1983), p. 527 online; Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), p. 15 online.

- Christian Goudineau translates these qualities into French as "sa grande valeur" and "sa haute culture" (César et la Gaule, p. 74).

- Brian A. Krostenko, "Beyond (Dis)belief: Rhetorical Form and Religious Symbol in Cicero's De Divinatione," Transactions of the American Philological Association 130 (2000), p. 364. The word humanitas first begins to be used regularly at this time, and its meaning evolves in later Latin literature.

- Cicero uses the word humanitas five times in the speech Pro Ligario in regard to Caesar, as noted by William C. McDermott, "In Ligarianam," Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 101 (1970), p. 336. Also John H. Collins, “Caesar and the Corruption of Power,” Historia 4 (1955), pp. 451, 455.

- De provinciis consularibus 29: hominum nationumque illarum humanitas et lepos. Brian A. Krostenko, Cicero, Catullus, and the Language of Social Performance (University of Chicago Press, 2001), pp. 193–194 online: "Even in this relatively straightforward, humorous passage the exclusionary force of the language of social performance is plainly present."

- Krostenko, Cicero, Catullus, and the language of social performance pp. 197, 212 et passim. See also Lindsay Hall on Caesar's "linguistic nationalism," "Ratio and Romanitas in the Bellum Gallicum," in Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter, pp. 11–43.

- W.J. Slater, "Handouts at Dinner," Phoenix 54 (2000), p. 120.

- John Milton in the Areopagitica translates this phrase as "preferred the natural wits of Britain before the laboured studies of the French", with an emphasis not lacking in other Anglocentric translations.

- Tacitus, Agricola 21: Iam vero principum filios liberalibus artibus erudire, et ingenia Britannorum studiis Gallorum anteferre, ut qui modo linguam Romanam abnuebant, eloquentiam concupiscerent. Inde etiam habitus nostri honor et frequens toga; paulatimque discessum ad delenimenta vitiorum, porticus et balinea et conviviorum elegantiam. Idque apud imperitos humanitas vocabatur, cum pars servitutis esset. For discussion of humanitas and Gallo-Roman acculturation, see Greg Woolf, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 54-70, also p. 53 online.

- Jane Webster, "Creolizing the Roman Provinces," American Journal of Archaeology 105 (2001), p. 210, quoting also Greg Woolf, "Beyond Romans and Natives," World Archaeology 28 (1997), p. 55: "despite its applicability to humankind, humanitas embodied 'concepts of culture and conduct that were regarded by the Romans as the hallmarks of the aristocracy in particular.'"

- Propterea quod a cultu atque humanitate provinciae longissime absunt.

- Summa virtute et humanitate (BG 1.46.4). Cicero also collocates humanitas and virtus, as at De oratore 3.1 and 57. In his speech Pro Flacco, delivered on behalf of Lucius Flaccus, Cicero associates humanitas with Athens and virtus with Sparta (62–63).

- Gendered, as distinguished from homo, homines, "people, human beings."

- Elaine Fantham, "The Ambiguity of Virtus in Lucan's Civil War and Statius' Thebiad," Arachnion 3 online.

- "Although battlefields might be thought to be its best proving grounds, Cicero used the term [virtus] to denote general excellence in other areas of activity, ... all with the over-arching notion that it was something that existed only in action," notes Andrew J.E. Bell, "Cicero and the Spectacle of Power," Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997), p. 9. See also Edwin S. Ramage, “Aspects of Propaganda in the De bello gallico: Caesar’s Virtues and Attributes,” Athenaeum 91 (2003) 331–372. Ramage sees humanitas as belonging to a class of virtues encompassing "kindness and generosity," associated in Caesar with qualities such as clementia ("clemency, leniency"), beneficium ("service, favor, benefit"), benevolentia ("goodwill, benevolence"), indulgentia or indulgeo ("leniency, mildness, kindness, favor," or the verbal action of granting these), mansuetudo ("mildness"), misericordia ("compassion, pity"), and liberalitas or liberaliter ("generosity" or to do something "freely, generously, liberally").

- Rhiannon Evans, Utopia Antiqua: Readings of the Golden Age and Decline at Rome (Routledge, 2008), pp. 156–157 online.

- Helvetii (1.1.4, 1.2.2, 1.13.4 thrice), Boii (1.28.4), Aedui (1.31.7).

- Bellum Gallicum 1.40.4 and 1.51.1, and of the 10th Legion in particular at 1.40.15.

- Andrew J.E. Bell, "Cicero and the Spectacle of Power," Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997), p. 9. Ariovistus claims the quality for his Germani and for himself (BG 1.36.7 and 1.44.1), but while this German virtus is affirmed by Gauls and merchants, causing unease among the army, it is downplayed by Caesar (1.39.1 and 1.40.8). On the rhetoric of virtus and competing claims to it in the Bellum Gallicum, see Louis Rawlings, “Caesar’s Portrayal of Gauls as Warriors,” in Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter (Classical Press of Wales, 1998).

- Gaius Volusenus (3.5.2), Quintus Cicero (5.48.6), and Titus Labienus (7.59.6); see Myles Anthony McDonnell, Roman manliness: virtus and the Roman Republic (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 308 online. The centurions Vorenus and Pullo bandy the word between themselves at 5.44.

- Commius at Bellum Gallicum 4.21.7, the only instance of the word virtus in Book 4; Tasgetius at 5.25.2, in noting that having been installed as king by Caesar, he was murdered by his own people three years into his reign.

- At one time, the dominant scholarly view held that the Commentarii were published as a collection, reworked from Caesar's annual report as proconsul to the Roman senate; internal contradictions, narrative discontinuities, and gaffes (such as Caesar's insistence on the loyalty of Commius of the Atrebates, and his failure to anticipate the uprising of Vercingetorix and the Arverni and the Aedui) are among the questions that cause scholars to find serial publication more likely, with the collected edition appearing as a public relations effort at the outset of Caesar's civil war with Pompeius Magnus and the senatorial elite.

- T.P. Wiseman, “The Publication of De Bello Gallico,” in Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter, pp. 1–9.

- Varro Atacinus, or P. Terentius Varro, was a native of the Narbonensis, identified by his toponymic cognomen as associated with the Aude River (ancient Atax) and thus distinguished from the more famous Varro; whether he was an ethnic Celt or a Roman colonist can be debated. Though his work survives only in fragments, the Augustan poets regarded him highly.

- Edward Courtney, The Fragmentary Latin Poets (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 235–253.