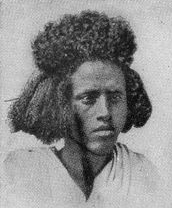

Fuzzy-Wuzzy

"Fuzzy-Wuzzy" is a poem by the English author and poet Rudyard Kipling, published in 1892 as part of Barrack Room Ballads. It describes the respect of the ordinary British soldier for the bravery of the Hadendoa warriors who fought the British army in the Sudan and Eritrea.

Background

"Fuzzy-Wuzzy" was the term used by British colonial soldiers for the nineteenth-century Beja warriors supporting the Sudanese Mahdi in the Mahdist War. The term Fuzzy Wuzzy is purely of English origin.

The Beja people were one of several broad multi-tribal groupings supporting the Mahdi, and were divided into three tribes, Haddendowa, Amarar and Bishariyyin. All of these are semi-nomadic and inhabit the Sudan's Red Sea Hills, Libyan Desert, and southern Egypt. The Beja provided a large number of warriors to the Mahdist forces. They were armed with swords and spears and some of them carried breech-loaded rifles which had been captured from the Egyptian forces, and some of them had acquired military experience in the Egyptian army.

The poem

Kipling's poem "Fuzzy-Wuzzy" praises the Hadendoa for their martial prowess, because "for all the odds agin' you, Fuzzy-Wuz, you broke the square". This could refer to either or both historical battles between the British and Mahdist forces where British infantry squares were broken. The first was at the Battle of Tamai, on 13 March 1884, and the second was on 17 January 1885[1] during the Battle of Abu Klea. Kipling's narrator, an infantry soldier, speaks in admiring terms of the "Fuzzy-Wuzzies", praising their bravery which, although insufficient to defeat the British, did at least enable them to boast of having "broken the square"—an achievement which few other British foes could claim.

Writing in The Atlantic in June 2002, Christopher Hitchens noted "[Yet] where Kipling excelled—and where he most deserves praise and respect—was in enjoining the British to avoid the very hubris that he had helped to inspire in them. His 'Recessional' is only the best-known and most hauntingly written of many such second thoughts. ... There is also 'The Lesson', a poem designed to rub in the experience of defeat in Africa, and (though it is abysmal as poetry) 'Fuzzy-Wuzzy', a tribute to the fighting qualities of the Sudanese."[2]

Other references

T. S. Eliot included the poem in his 1941 collection A Choice of Kipling's Verse.

In the Tintin book The Crab with the Golden Claws, "Fuzzy-Wuzzy" is one of the epithets Captain Haddock shouts at his enemies.

In the film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Caractacus Potts' father refers to the "Fuzzy-Wuzzys" when speaking of his time in the army. Additionally, in the BBC situation comedy Dad's Army, Lance Corporal Jones (Clive Dunn) continually refers to the Fuzzy-Wuzzies in his reminiscences about his days fighting in the Sudan under General Kitchener.

In the film The Four Feathers (1939), when the camp of the Mahdi supporters is shown (at 49.35 min.) a title appears: THE KALIPHA'S ARMY OF DERVISHES AND FUZZY WUZZIES ON THE NILE. Also, towards the end of the film (1:52.40 min.) the old General states: "All you boys had to do was deal with Fuzzy-Wuzzy."

In the 1964 film Zulu, Michael Caine's character reports the strength of the opposing force to his commander in the British Army before the Battle of Rorke's Drift by saying "Good Lord, sir! There are thousands of the Fuzzy-Wuzzies!"

During the hard fought Kokoda Track campaign during World War II, Australian soldiers called the local Papuan stretcher bearers "Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels".[3]

See also

References

- Parsons, Michael (23 May 2015). "Brick from the Mahdi's tomb used as a Big House doorstop". The Irish Times. Dublin. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Hitchens, Christopher (June 2002). "A Man of Permanent Contradictions". The Atlantic. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- "Kokoda: 'Fuzzy wuzzy angels'". Australia's War 1939–1945. Department of Veterans' Affairs, Australian Government. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Full poem at The Kipling Society website

- Historical background to the Kipling poem

- Kipling.org line-by-line explanation of references