Fusidic acid

Fusidic acid is an antibiotic that is often used topically in creams and eyedrops but may also be given systemically as tablets or injections. The global problem of advancing antimicrobial resistance has led to a renewed interest in its use recently.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Fucidin, Fucithalmic, Stafine |

| Other names | Sodium fusidate |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 91% oral bioavailability |

| Protein binding | 97 to 99% |

| Elimination half-life | Approximately 5 to 6 hours in adults |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.027.506 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

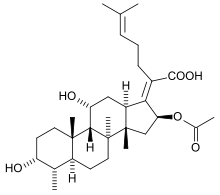

| Formula | C31H48O6 |

| Molar mass | 516.709 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Pharmacology

Fusidic acid acts as a bacterial protein synthesis inhibitor by preventing the turnover of elongation factor G (EF-G) from the ribosome. Fusidic acid is effective primarily on Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus species, Streptococcus species,[2] and Corynebacterium species. Fusidic acid inhibits bacterial translation and does not kill the bacteria, and is therefore termed "bacteriostatic".

Fusidic acid is an antibiotic, derived from the fungus Fusidium coccineum and was developed by Leo Pharma in Ballerup, Denmark and released for clinical use in the 1960s. It has also been isolated from Mucor ramannianus and Isaria kogana. The drug is licensed for use as its sodium salt sodium fusidate, and it is approved for use under prescription in South Korea, Japan, Canada, the EU, Australia, New Zealand, Colombia, Thailand, India and Taiwan. A different oral dosing regimen, based on the compound's pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) profile is in clinical development in the U.S.[3] as Taksta.

Uses

Fusidic acid is active in vitro against Staphylococcus aureus, most coagulase-positive staphylococci, Beta-hemolytic streptococci, Corynebacterium species, and most clostridium species. Fusidic acid has no known useful activity against enterococci or most Gram-negative bacteria (except Neisseria, Moraxella, Legionella pneumophila, and Bacteroides fragilis). Fusidic acid is active in vitro and clinically against Mycobacterium leprae but has only marginal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

One important clinical use of fusidic acid is its activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[4] Although many strains of MRSA remain sensitive to fusidic acid, there is a low genetic barrier to drug resistance (a single point mutation is all that is required), fusidic acid should never be used on its own to treat serious MRSA infection and should be combined with another antimicrobial such as rifampicin when administering oral or topical dosing regimens approved in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere. However, resistance selection is low when pathogens are challenged at high drug exposure.[5] An orally-administered mono-therapy with a high loading dose is under development in the United States.[3]

Topical fusidic acid is occasionally used as a treatment for acne vulgaris.[6] As a treatment for acne, fusidic acid is often partially effective at improving acne symptoms.[7] However, research studies have indicated that fusidic acid is not as highly active against Cutibacterium acnes as many other antibiotics that are commonly used as acne treatments.[8] Fusidic acid is also found in several additional topical skin and eye preparations (e.g. Fucibet), although its use for these purposes is controversial.[9]

Fusidic acid is being tested for indications beyond skin infections. There is evidence from compassionate use cases that fusidic acid may be effective in the treatment of patients with prosthetic joint-related chronic osteomyelitis.[10]

Dose

Fusidic acid should not be used on its own to treat S. aureus infections when used at low drug dosages. However, it may be possible to use fusidic acid as monotherapy when used at higher doses.[3] The use of topical preparations (skin creams and eye ointments) containing fusidic acid is strongly associated with the development of resistance,[11] and there are voices advocating against the continued use of fusidic acid monotherapy in the community.[9] Topical preparations used in Europe often contain fusidic acid and gentamicin in combination, which helps to prevent the development of resistance.

Depending on the reason for which sodium fusidate is prescribed, the adult dose can be 250 mg twice a day and or up to 750 mg three times a day. (Skin conditions normally need the smaller dose.) It is available in tablet and suspension form.[12] An oral dosing regimen is in clinical development in the U.S. based on the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of the compound. It incorporates a dose of 1,500 mg twice on the first day followed by 600 mg twice-daily. It has been demonstrated in an in vitro model to have a low potential for selection of resistant organisms.[3]

There is an intravenous preparation available, but it is irritant to veins, causing phlebitis. Most people absorb the drug extremely well after taking it orally, so, if a patient can swallow, there is not much need to administer it intravenously, even if used to treat endocarditis (infection of the heart chambers).

Cautions

There is inadequate evidence of safety in human pregnancy. Animal studies and many years of clinical experience suggest that fusidic acid is devoid of teratogenic effects (birth defects), but fusidic acid can cross the placental barrier.[13]

Side-effects

Fucidin tablets and suspension, whose active ingredient is sodium fusidate, occasionally cause liver upsets, which can produce jaundice (yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes). This condition will almost always get better after the patient finishes taking Fucidin tablets or suspension. Other related side-effects include dark urine and lighter-than-usual feces. These, too, should normalize when the course of treatment is completed.[14] Patients taking the drug should tell their doctors if they notice these side effects.

Resistance

In vitro susceptibility studies of U.S. strains of several bacterial species such as S. aureus, including MRSA and coagulase negative Staphylococcus, indicate potent activity against these pathogens[15][16][17]

In the UK and Australia, susceptibility is defined as a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.25 mg/l or 0.5 mg/l or less. Resistance is defined as an MIC of 2 mg/l or more. In laboratories using disc diffusion methods, susceptibility for a 2.5 µg disc is defined as a zone of 22 mm or more, and resistance is defined as a zone of 17 mm or less; intermediate values are defined as intermediate resistance. These susceptibility criteria are based on lower dosing regimens used outside of the U.S. Clinical trials in the U.S. incorporate a different dosing regimen that results in higher blood levels. Therefore, the U.S. dosing regimen may warrant different susceptibility criteria.

Mechanisms of resistance have been extensively studied only in Staphylococcus aureus. The most important mechanism is the development of point mutations in fusA, the chromosomal gene that codes for EF-G. The mutation alters EF-G so that fusidic acid is no longer able to bind to it.[18][19] Resistance is readily acquired when fusidic acid is used alone and commonly develops during the course of treatment. As with most other antibiotics, resistance to fusidic acid arises less frequently when used in combination with other drugs. For this reason, fusidic acid should not be used on its own to treat serious Staph. aureus infections. However, at least in Canadian hospitals, data collected between 1999 and 2005 showed rather low rate of resistance of both methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant to fusidic acid, and mupirocin was found to be the more problematic topical antibiotic for the aforementioned conditions.[20]

Some bacteria also display 'fusB-type' resistance. This resistance mechanism is mediated by fusB, fusC, and fusD genes found on plasmids.[21] The product of fusB-type resistance genes is a 213-residue cytoplasmic protein which interacts in a 1:1 ratio with EF-G. FusB-type proteins bind in a region distinct from fusidic acid to induce a conformational change which results in liberation of EF-G from fusidic acid, allowing the elongation factor to participate in another round of ribosome translocation.[22]

FusB-type resistance is common in clinical MRSA isolates and is observed in over 70% of some cohorts [23]

Interactions

Fusidic acid should not be used with quinolones, with which they are antagonistic. Although clinical practice over the past decade has supported the combination of fusidic acid and rifampicin, a recent clinical trial showed that there is an antagonic interaction when both antibiotics are combined.[24]

It has been reported on August 8, 2008, that the Irish Medicines Board was investigating the death of a 59-year-old Irish man who developed rhabdomyolysis after combining atorvastatin and fusidic acid, and three similar cases.[25] In August, 2011, the UK's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a Drug Safety Update warning that "Systemic fusidic acid (Fucidin) should not be given with statins because of a risk of serious and potentially fatal rhabdomyolysis."[26]

It is delivered as an ointment, as a cream, as eye drops, or in tablet form.

Trade names and preparations

- Fusitop-HC (in Bangladesh, Square Pharmaceuticals Ltd.)

- Usidin cream (in Pakistan, Pacific Pharmaceuticals Ltd.)

- Fucidin (of Leo in Canada)

- Fucidin H (topical cream with corticosteroid - Leo)

- Fucidin (of Leo in UK/ Leo-Ranbaxy-Croslands in India)

- Fucidine (of Leo in France)

- Fucidin (of Leo in Norway and Israel)

- Fucidin (of Adcock Ingram, licensed from Leo, in South Africa)

- Fucithalmic (of Leo in the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark and Portugal)

- Fucicort (topical mixture with hydrocortisone)

- Fucibet (fusidic acid/betamethasone valerate topical cream)

- Ezaderm (topical mixture with betamethasone)(of United Pharmaceutical "UPM" in Jordan)

- Fuci (of pharopharm in Egypt)

- Fucizon (topical mixture with hydrocortisone of pharopharm in Egypt)

- Foban (topical cream in New Zealand)

- Betafusin (fusidic acid/betamethasone valerate topical cream in Greece)

- Betafucin (2% fusidic acid/1% betamethasone valerate topical cream in Egypt)(of Delta Pharma S.A.E., A.R.E. (Egypt))

- Fusimax (of Roussette in India)

- Fusiderm (topical cream and ointment by Indi Pharma in India)

- Fusid (in Nepal)

- Fudic (topical cream in India)

- Fucidin (후시딘, of Dong Wha Pharm in South Korea)

- Dermy (Topical cream of W. Woodwards in Pakistan)

- Fugen Cream (膚即淨軟膏 in Taiwan)

- Phudicin Cream (in China; 夫西地酸[27])

- Fucidin Fusidic Acid (in China;夫西地酸 of Leo Laoratories Limited)

- Dermofucin cream, ointment and gel (in Jordan)

- Optifucin viscous eye drops (of API in Jordan)

- Verutex (of Roche in Brazil)

- Taksta (of Cempra in U.S. For export only in US)

- Futasole (of Julphar in Gulf and north Africa)

- Stanicid (2% ointment of Hemofarm in Serbia)

- Staphiderm Cream (Israel By Trima).

- Fuzidin (tablets of Biosintez in Russia)

- Fuzimet (ointment with methyluracil of Biosintez in Russia)

- Axcel Fusidic Acid (2% cream and ointment of Kotra Pharma, Malaysia)

- Ofusidic (eye drops produced by Orchidia pharmaceutical in Egypt

References

- Falagas, ME; Grammatikos, AP; Michalopoulos, A (2008). "Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics". Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 6 (5): 593–600. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.5.593. PMID 18847400.

- Leclercq, R; Bismuth, R; Casin, I; Cavallo, JD; Croize, J; Felten, A; Goldstein, F; Monteil, H; Quentin-Noury, C; Reverdy, M; Vergnaud, M; Roiron, R (2000). "In Vitro Activity of Fusidic Acid Against Streptococci isolated form Skin and Soft Tissue Infections". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45 (1): 27–29. doi:10.1093/jac/45.1.27. PMID 10629009.

- Moriarty SR, Clark K, Scott D, Degenhardt TP, Fernandes P, Craft JC, Corey GR, Still JG and Das A (2010). 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Abstract L1-1762

- Existing drug will cure hospital superbug MRSA, say scientists – The Guardian, 17 January 2007.Accessed 2008-01-17.

- O'Neill, AJ; Chopra, I (2004). "Preclinical evaluation of novel antibacterial agents by microbiological and molecular techniques". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 13 (8): 1045–1063. doi:10.1517/13543784.13.8.1045. PMID 15268641.

- Spelman. (1999). "Fusidic acid in skin and soft tissue infections". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 12 Suppl 2: S59–66. doi:10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00074-0. PMID 10528787.

- "Fusidic Acid and Acne Vulgaris". ScienceOfAcne.com. 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- Sommer; et al. (1997). "Investigation of the mechanism of action of 2% fusidic acid lotion in the treatment of acne vulgaris". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 22 (5): 211–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.2530670.x. PMID 9536540.

- Howden BP, Grayson ML (2006). "Dumb and dumber—the potential waste of a useful antistaphylococcal agent: emerging fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus". Clin Infect Dis. 42 (3): 394–400. doi:10.1086/499365. PMID 16392088.

- Wolfe, CR (2011) Case report: treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52(Supplement 7): S538-S541

- Mason BW, Howard AJ, Magee JT (2003). "Fusidic acid resistance in community isolates of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and fusidic acid prescribing". J Antimicrob Chemother. 51 (4): 300–3. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg190. PMID 12654748.

- Fucidin data sheet archived by New Zealand government. December 2005 Archived 2007-10-26 at the Wayback Machine.Accessed: 2007-09-09.

- Fucidin) UK data sheet archived at the electronic Medicines Compendium. June 1997 Archived 2008-06-11 at the Wayback Machine.Accessed: 2007-09-09.

- Fucidin patient information leaflet, archived by Government of Victoria, Australia Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed: 2007-09-09.

- Castanheira, M; Watters, AA; Bell, JM; Turnidge, JD; Jones, RN (2010). "Fusidic acid resistance rates and prevalence of resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus species isolated in North America and Australia, 2007-2008". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (9): 3614–3617. doi:10.1128/aac.01390-09. PMC 2934946. PMID 20566766.

- Pfaller, M; Castaneira, M; Sader, H; Jones, R (2010). "Evaluation of the activity of fusidic acid tested against contemporary Gram-positive clinical isolates from the USA and Canada". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 35 (3): 282–287. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.023. PMID 20036520.

- Castanheira M, Mendes RE, Rhomberg PR and Jones RN (2010). Activity of fusidic acid tested against contemporary Staphylococcus aureus collected from United States hospitals. Infectious Diseases Society of America, 48th Annual Meeting, Abstract 226.

- Turnidge J, Collignon P (1999). "Resistance to fusidic acid". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 12 (Suppl 2): S35–44. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(98)00072-7. PMID 10528785.

- Besier S, Ludwig A, Brade V, Wichelhaus TA (2003). "Molecular analysis of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus". Mol Microbiol. 47 (2): 463–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03307.x. PMID 12519196.

- Rennie RP (2006). "Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to fusidic acid:Canadian data". J Cutan Med Surg. 10 (6): 277–280. doi:10.2310/7750.2006.00064. PMID 17241597.

- O'Neill, A. J.; McLaws, F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Henriksen, A. S.; Chopra, I. (2007). "Genetic Basis of Resistance to Fusidic Acid in Staphylococci". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 51: 1737–1740. doi:10.1128/AAC.01542-06.

- Cox, Georgina; Thompson, Gary S.; Jenkins, Huw T.; Peske, Frank; Savelsbergh, Andreas; Rodnina, Marina V.; Wintermeyer, Wolfgang; Homans, Steve W.; Edwards, Thomas A.; O'Neill, Alexander J. (2012). "Ribosome clearance by FusB-type proteins mediates resistance to the antibiotic fusidic acid". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109: 2102–2107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117275109.

- McLaws, F. B.; Larsen, A. R.; Skov, R. L.; Chopra, I.; O'Neill, A. J. (2011). "Distribution of Fusidic Acid Resistance Determinants in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 55: 1173–1176. doi:10.1128/AAC.00817-10.

- Pushkin R, Maria D, Iglesias-Ussel K, MacLauchlin C, Mould D, Berkowitz R, et al. (2016). "A Randomized Study Evaluating Oral Fusidic Acid (CEM-102) in Combination With Oral Rifampin Compared With Standard-of-Care Antibiotics for Treatment of Prosthetic Joint Infections: A Newly Identified Drug–Drug Interaction". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (12): 1599–1604. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw665. PMID 27682068.

- Riegel, Ralph (2008-08-08). "Man died after rare medical reaction to cholesterol drug". Irish Independent.

- Drug Safety Update Sept 2011, vol 5 issue 2: A1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-09-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fusidic acid. |