French ironclad Requin

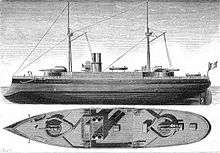

Requin was an ironclad barbette ship built for the French Navy in the late 1870s and early 1880s. She was last member of the four-ship Terrible class. They were built as part of a fleet plan started in 1872, which by the late 1870s had been directed against a strengthening Italian fleet. The ships were intended for coastal operations, and as such had a shallow draft and a low freeboard, which greatly hampered their seakeeping and thus reduced their ability to be usefully employed outside of coastal operations after entering service. Armament consisted of a pair of 420 mm (16.5 in) guns in individual barbettes, the largest gun ever mounted on a French capital ship. Requin was laid down in 1878 and was completed in 1887.

.jpg) Requin in Britain in 1892 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Requin |

| Laid down: | December 1878 |

| Launched: | June 1885 |

| Commissioned: | December 1888 |

| Stricken: | 1920 |

| Fate: | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 7,530 long tons (7,650 t) |

| Length: | 82.75 m (271 ft 6 in) pp |

| Beam: | 17.98 m (59 ft) |

| Draft: | 7.98 m (26 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 14.5 to 15 kn (26.9 to 27.8 km/h; 16.7 to 17.3 mph) |

| Complement: | 373 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Unlike her sister ships that served in the Mediterranean Fleet, Requin spent her early career in the Northern Squadron in the English Channel. In 1891, the unit was sent to visit Britain and Russia. She was withdrawn from service in 1896 to be modernized with new armament, propulsion system, and armor. Work was completed in 1901 and the next year she returned to service as a guard ship based in Cherbourg. She was the only member of the class to see action during World War I, during which she was stationed in the Suez Canal to defend the waterway against attacks from the Ottoman Empire. She helped to repel an attack in February 1915, but saw little activity thereafter. She was ultimately broken up in 1920.

Design

The Terrible class of barbette ships was designed in the late 1870s as part of a naval construction program that began under the post-Franco-Prussian War fleet plan of 1872. By 1877, the Italian fleet under Benedetto Brin had begun building powerful new ironclads of the Caio Duilio and Italia classes, which demanded a French response, beginning with the ironclad Amiral Duperré of 1877. In addition, the oldest generation of French ironclads, built in the early-to-mid 1860s, were in poor condition and necessitated replacement. The Terrible class was intended to replace old monitors that had been built for coastal defense. The Terribles were based on the Amiral Baudin-class ironclads, but were reduced in size to allow them to operate in shallower waters.[1]

Requin was 82.75 m (271 ft 6 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 17.98 m (59 ft) and a draft of 7.98 m (26 ft 2 in). She displaced 7,530 long tons (7,650 t) and had a relatively low freeboard. She was fitted with a pair of pole masts equipped with spotting tops for her main battery guns. The crew consisted of 373 officers and enlisted men. Her propulsion machinery consisted of two compound steam engines, each driving a screw propeller, with steam provided by ten coal-burning fire-tube boilers. Her engines were rated to produce 6,500 indicated horsepower (4,800 kW) for a top speed of 14.5 to 15 knots (26.9 to 27.8 km/h; 16.7 to 17.3 mph).[2]

Her main armament consisted of two 420 mm (16.5 in), 22-caliber guns in individual barbette mounts, one forward and one aft on the centerline.[2] They were the largest guns ever carried by a French capital ship.[3] These guns were supported by a secondary battery of four 100 mm (3.9 in) guns carried in individual pivot mounts with gun shields. For defense against torpedo boats, she carried two or four 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon and sixteen 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolvers, all in individual mounts. Her armament was rounded out with four 356 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes.[2]

The ship was protected with compound armor; her belt was 203 to 508 mm (8 to 20 in) thick and extended for the entire length of the hull. At even normal loading, the belt was nearly entirely submerged, reducing its effectiveness significantly. The barbettes for the main battery were 457 mm (18 in) thick and the supporting tubes that connected them to the ammunition magazines were 203 mm. Her conning tower was 25 mm (0.98 in) thick, as were the shields for the 100 mm guns.[2]

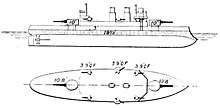

Modifications

Requin was modernized in 1898, having her old 420 mm guns replaced with a pair of 274 mm (10.8 in) Modèle 1893/1896 guns; these were 40-caliber guns. Her secondary battery was replaced with quick-firing versions of 100 mm guns, with an additional pair being installed. The light battery was also revised to fourteen 47 mm guns. All four of her torpedo tubes were also removed. Her propulsion system was replaced with a pair of triple-expansion steam engines and twelve Niclausse boilers, which were the water-tube type. The heavy compound armor for the main battery barbettes was replaced with 254 mm (10 in) of new, stronger Harvey armor. As a result of these changes, her crew was reduced to 332 officers and men.[2][4]

Service history

The keel for Requin, the last member of the class to be built, was laid down in December 1878 at the Forges et Chantiers de la Gironde shipyard in Lormont. She was launched in June 1885 and was completed in December 1888.[2] After they entered service, the Terrible-class ships were found to have very poor seakeeping as a result of their shallow draft and insufficient freeboard, even in the relatively sheltered waters of the Mediterranean Sea. The Navy had little use for the ships, and through the 1880s and 1890s, a series of French naval ministers sought to find a role for the vessels, along with another ten coastal-defense type ironclads built during that period. The ships frequently alternated between the Mediterranean Squadron and the Northern Squadron, the latter stationed in the English Channel, but neither location suited their poor handling.[5]

During the 1890 fleet maneuvers, Requin served in the 2nd Division of the 1st Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet. At the time, the division also included the ironclads Marengo and Furieux, the former serving as the squadron flagship for Vice Admiral Charles Duperré. The ships concentrated off Oran, French Algeria on 22 June and then proceeded to Brest, France, arriving there on 2 July for combined operations with the ships of the Northern Squadron. The exercises began four days later and concluded on 25 July, after which Requin and the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet returned to Toulon.[6] In 1891, a French squadron that included Requin and the ironclads Marengo, Marceau, and Furieux, under the command of Admiral Alfred Gervais was sent to visit Kronstadt, Russia. There, it was inspected by Czar Alexander III. On the return voyage, the fleet stopped in Spithead, Great Britain, where Queen Victoria reviewed the ships.[7][8]

During a voyage from Saint-Malo to Brest in 1892, Requin took on significant amounts of water, demonstrating the poor seakeeping of her class; an estimated 15 to 20 long tons (15 to 20 t) of water flooded her forward barbette, and her battery deck was thoroughly washed out. That year, she served as the flagship of the Northern Squadron, which at that time also included Furieux on active duty, with another three ironclads in reserve.[9] In 1893, Requin participated in the fleet's maneuvers in the English Channel, serving in Squadron B, along with the ironclads Suffren and Fulminant.[10] She remained in the unit the following year, which was kept in commission for four months of the year. By that time, the unit consisted of Requin, Suffren, Furieux, and the ironclad Victorieuse.[11]

She was removed from the squadron in 1896, her place having been taken by newer coastal defense ships.[12] The ship was modernized in the late 1890s, with work beginning in Cherbourg in 1896. Her armament was revised with new main and secondary guns and all of her torpedo tubes were removed. She also received new boilers and engines during the reconstruction, which was completed in 1901.[2][13][14] After returning to service by 1902, she resumed her assignment to the Northern Squadron, where she was based in Cherbourg with the gunboat Styx as harbor guard ships.[15] By 1906, she was attached to the Reserve Squadron in the Mediterranean Fleet for the annual maneuvers, along with her sister ships Indomptable, Caïman, the ironclad Hoche, and the pre-dreadnought battleship Charles Martel.[16]

World War I

Requin saw service in the eastern Mediterranean and in the Suez Canal zone during World War I.[2] She was stationed in Ismailia in December 1914 to help guard the canal from Ottoman attacks. In January 1915, some of the French and British cruisers in the canal zone were sent to patrol the southern Anatolian coast between Mersin and Smyrna, and Requin was moved further north to support them if necessary. Early that month, she was sent to join the patrol itself, but in mid-January, additional cruisers arrived to relieve Requin, which was sent back to the canal to resume guard duties. A berth was dredged in Lake Timsah in the Nile Delta for Requin, where she supported the ground forces defending the northern end of the canal.[17]

Toward the end of the month, an Ottoman force approached the canal, prompting the French to send the protected cruiser D'Entrecasteaux to join Requin in Lake Timsah. The attack came in stages in early February, and on the 3rd, Requin was heavily engaged in helping to repel the assault. She came under fire from Ottoman field artillery batteries, but she neutralized them with her forward 274 mm gun before they could score any hits. The Ottoman attack quickly broke down in the face of the heavy Anglo-French resistance. A small Ottoman force of around 400 men was detected reconnoitering Allied positions in late March, which prompted Requin to prepare for another attack, though no other Ottoman forces were in the area and the reconnaissance party was dispersed.[18] After the war, Requin was stricken from the naval register in 1920 and was subsequently sold for scrap.[2]

Notes

- Ropp, pp. 92, 97–98.

- Gardiner, p. 291.

- Ropp, p. 99.

- Brassey & Leyland, p. 24.

- Ropp, p. 180.

- Brassey 1891, pp. 33–40.

- Feron, pp. 71–72.

- Brassey 1892, p. 7.

- Brassey 1893, pp. 69–70.

- Thursfield, p. 95.

- Brassey 1895, p. 50.

- Brassey 1896, p. 64.

- Weyl, p. 30.

- Leyland 1901, p. 41.

- Brassey 1902, p. 48.

- Leyland 1907, p. 103.

- Corbett, pp. 74, 79.

- Corbett, pp. 112–117, 292.

References

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1891). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–40. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1892). "Progress of the British Navy, 1891–92". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 1–7. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). "Chapter IV: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 66–73. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1896). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–72. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. & Leyland, John (1903). "Chapter II: Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 21–56. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1901). "Chapter III: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–70. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1907). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: The French and Italian Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 102–111. OCLC 496786828.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1921). Naval Operations: From The Battle of the Falklands to the Entry of Italy Into the War in May 1915. II. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 924170059.

- Feron, Luc (1985). "French Battleship Marceau". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. XXII (1): 68–78. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1894). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 71–102. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 16–55. OCLC 496786828.