Fort Knox

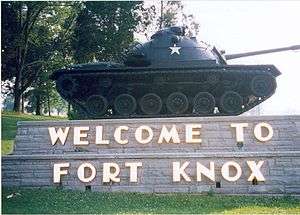

Fort Knox is a United States Army post in Kentucky, south of Louisville and north of Elizabethtown. It is adjacent to the United States Bullion Depository, which is used to house a large portion of the United States' official gold reserves. The 109,000 acre (170 sq mi, 441 km 2) base covers parts of Bullitt, Hardin, and Meade counties. It currently holds the Army Human Resources Center of Excellence to include the Army Human Resources Command. It is named in honor of Henry Knox, Chief of Artillery in the American Revolutionary War and first United States Secretary of War.

| Fort Knox | |

|---|---|

| Kentucky | |

| |

Location of Fort Knox in Kentucky | |

| Coordinates | 37.92°N 85.96°W |

| Type | Military base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by |

|

| Site history | |

| Built | 1918 |

| In use |

|

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | Major General John Evans Jr.[1] |

For 60 years, Fort Knox was the home of the U.S. Army Armor Center and the U.S. Army Armor School, and was used by both the Army and the Marine Corps to train crews on the American tanks of the day; the last was the M1 Abrams main battle tank. The history of the U.S. Army's Cavalry and Armored forces, and of General George S. Patton's career, is shown at the General George Patton Museum[2] on the grounds of Fort Knox.

In 2011, the U.S. Army Armor School moved to Fort Benning, Georgia, where the Infantry School is also based.[3] In 2014, the U.S. Army Cadet Command relocated to Fort Knox and all summer training for ROTC cadets now takes place there.[4]

Bullion Depository

The United States Bullion Depository, often known as Fort Knox, is a fortified vault building adjacent to the Fort Knox Army Post. It is operated by the United States Department of the Treasury and stores over half the country's gold reserves. It is protected by the United States Mint Police and is well known for its physical security.

The depository was built by the Treasury in 1936 on land transferred to it from Fort Knox.[5] Early shipments of gold totaling almost 13,000 metric tons [6] were escorted by combat cars of the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment to the depository.[7] It has in the past safeguarded other precious items, such as the Constitution of the United States and the United States Declaration of Independence.[8]

Census-designated place

Parts of the base in Hardin and Meade counties form a census-designated place (CDP), which had a population of 12,377 at the 2000 census and 10,124 at the 2010 census.

Patton Museum

The George S. Patton Museum and Center of Leadership at Fort Knox includes an exhibit highlighting leadership issues that arose from the attacks of September 11, 2001, which includes two firetrucks. One of them, designated Foam 161, was partially charred and melted in the attack upon the Pentagon. Fort Knox is also the location of the United States Army's Human Resources Command's Timothy Maude Center of Excellence, which was named in honor of Lieutenant General Timothy Maude, the highest-ranking member of the U.S. military to die in the attacks of 11 September 2001.[9]

In 2011, the U.S. Army Armor School was relocated to "The Maneuver Center of Excellence" at FT Benning, GA.1

History

Fortification

Fortifications were constructed near the site in 1861, during the Civil War when Fort Duffield was constructed. Fort Duffield was located on what was known as Muldraugh Hill on a strategic point overlooking the confluence of the Salt and Ohio Rivers and the Louisville and Nashville Turnpike. The area was contested by both Union and Confederate forces. Bands of organized guerrillas frequently raided the area during the war. John Hunt Morgan[10] and the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment of the Confederate Army raided the area before staging his famous raid across Indiana and Ohio.[11]

Post Civil War

After the war, the area now occupied by the Army was home to various small communities. In October 1903, military maneuvers for the Regular Army and the National Guards of several states were held at West Point, Kentucky and the surrounding area.[12] In April 1918, field artillery units from Camp Zachary Taylor arrived at West Point for training. 20,000 acres (8,100 ha) near the village of Stithton were leased to the government and construction for a permanent training center was started in July 1918.

New camp

The new camp was named after Henry Knox, the Continental Army's chief of artillery during the Revolutionary War and the country's first Secretary of War. The camp was extended by the purchase of a further 40,000 acres (16,000 ha) in June 1918 and construction properly began in July 1918. The building program was reduced following the end of the war and reduced further following cuts to the army in 1921 after the National Defense Act of 1920. The camp was greatly reduced and became a semi-permanent training center for the 5th Corps Area for Reserve Officer training, the National Guard, and Citizen's Military Training Camps (CMTC). For a short while, from 1925 to 1928, the area was designated as "Camp Henry Knox National Forest."[13]

Air Corps use

The post contains an airfield, called Godman Army Airfield, that was used by the United States Army Air Corps, and its successor, the United States Army Air Forces as a training base during World War II. It was used by the Kentucky Air National Guard for several years after the war until they relocated to Standiford Field in Louisville. The airfield is still in use by the United States Army Aviation Branch.

Protection of America's founding documents

For protection after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States and the Gettysburg Address were all moved for safekeeping to the United States Bullion Depository until Major W. C. Hatfield ordered its release after the D-Day Landings on 19 September 1944.[14]

Mechanized military unit occupation

In 1931 a small force of the mechanized cavalry was assigned to Camp Knox to use it as a training site. The camp was turned into a permanent garrison in January 1932 and renamed Fort Knox. The 1st Cavalry Regiment arrived later in the month to become the 1st Cavalry Regiment (Mechanized).

In 1936 the 1st was joined by the 13th to become the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized). The site quickly became the center for mechanization tactics and doctrine. The success of the German mechanized units at the start of World War II was a major impetus to operations at the fort. A new Armored Force was established in July 1940 with its headquarters at Fort Knox with the 7th Cavalry Brigade becoming the 1st Armored Division. The Armored Force School and the Armored Force Replacement Center were also sited at Fort Knox in October 1940, and their successors remained there until 2010, when the Armor School moved to Fort Benning, Georgia. The site was expanded to cope with its new role. By 1943, there were 3,820 buildings on 106,861 acres (43,245 ha). A third of the post has been torn down within the last ten years, with another third slated by 2010.

1947 Universal Military Training Experimental Unit

In 1947, Fort Knox hosted the Universal Military Training Experimental Unit, a six-month project that aimed to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of providing new 18-20 year-old Army recruits with basic military training that emphasized physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. This project was undertaken with the aim of persuading the public to support President Harry S. Truman's proposal to require all eligible American men to undergo universal military training.[15][16]

Stripes (1981) was filmed using the exterior of Fort Knox but did not show the inside of the facility for security reasons.[17]

1993 shooting

On 18 October 1993, Arthur Hill went on a shooting rampage, killing three and wounding two before attempting suicide, shooting and severely wounding himself. The shooting occurred at Fort Knox's Training Support Center. Prior to the incident, Hill's coworkers claimed they were afraid of a mentally unstable person who was at work. Hill died on 21 October of his self-inflicted gunshot wound.[18][19][20]

2013 shooting

On 3 April 2013, a civilian employee was shot and killed in a parking lot on post. The victim was an employee of the United States Army Human Resources Command and was transported to the Ireland Army Community Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. This shooting caused a temporary lock-down that was lifted around 7 p.m. on the same day.[21][22] U.S. Army Sgt. Marquinta E. Jacobs, a soldier stationed at Fort Knox, was charged on 4 April with the shooting.[23] He pleaded guilty to charges of premeditated murder and aggravated assault, and was sentenced to 30 years in prison on 10 January 2014.[24]

Human Resources Command (HRC)

The Army Human Resources Command Center re-located to Fort Knox from the Washington D.C./Virginia area beginning in 2009. New facilities are under construction throughout Fort Knox, such as the new Army Human Resource Center, the largest construction project in the history of Fort Knox. It is a $185 million, three-story, 880,000-square-foot (82,000 m2) complex of six interconnected buildings, sitting on 104 acres (42 ha).

In May 2010, The Human Resource Center of Excellence, the largest office building in the state, opened at Fort Knox. The new center employs nearly 4,300 soldiers and civilians.[25]

Fort Knox High School

Fort Knox is one of only four Army posts (the others being Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Fort Meade, Maryland, and Fort Sam Houston, Texas) that still has a high school located on-post. Fort Knox High School, serving grades 9–12, was built in 1958 and has undergone only a handful of renovations since then, including a new building which was completed in 2007.

Units

Current[26]

- First Army Division East[27]

- V Corps[29]

- United States Army Human Resources Command

- U.S. Army Marketing and Engagement Brigade[30]

- 19th Engineer Battalion[31]

- 1st Sustainment Command (Theater)[32]

- 902nd Military Intelligence Group (United States)[33]

- U.S. Army Cadet Command[34] (responsible for Reserve Officers' Training Corps, senior mission command and installation commander)

- Ireland Army Community Hospital MEDDAC

- United States Army Recruiting Command[35]

- 3rd Recruiting Brigade

- U S Army Medical Recruiting Brigade

- 100th Infantry Division (United States)[36]

- Army Reserve Aviation Command[37]

- 84th Division (United States)[38]

- 83rd U.S. Army Reserve Readiness Training Center[39]

Previous

- 1st Armor Training Brigade

- 3rd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division (inactivated 2014)

- 16th Cavalry Regiment

- 1st Squadron

- 2nd Squadron

- 3rd Squadron

- 194th Armored Brigade

- 1st Cavalry Regiment

- 7th Squadron (Air)

- Troops A, B, C, D, & HHT

- 235th Aviation Co. (Attack Helicopter)

- 7th Squadron (Air)

- 81st Armored Regiment

- 1st Battalion

- 2nd Battalion

- 3rd Battalion

- 15th Cavalry Regiment

- 5th Squadron

- 6th Squadron

- 46th Infantry Regiment

- 1st Battalion

- 2nd Battalion

- 1st Cavalry Regiment

- 34th Military Police Detachment

- 46th Adjutant General Battalion (Reception)

- 100th Army Band

- 95th Infantry Division (United States) (moved to Fort Sill)

- 3rd Sustainment Command (Expeditionary) (moved to Fort Bragg)

- 113th Band

Source:[40]

Geography

Fort Knox is located at 37°54'09.96" North, 85°57'09.11" West, along the Ohio River. The depository itself is located at 37°52'59.59" North, 85°57'55.31" West.

According to the Census Bureau, the base CDP has a total area of 20.94 square miles (54.23 km2), of which 20.92 sq mi (54.18 km2) is land and 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2)—0.14%—is water.[41] Communities near Fort Knox include Brandenburg, Elizabethtown, Hodgenville, Louisville, Radcliff, Shepherdsville, and Vine Grove, Kentucky.[42] The Meade County city of Muldraugh is completely surrounded by Fort Knox.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Fort Knox has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[43]

Demographics

As of the census[44] of 2000, there were 12,377 people, 2,748 households, and 2,596 families residing on base. The population density was 591.7 inhabitants per square mile (228.5/km2). There were 3,015 housing units at an average density of 144.1/sq mi (55.6/km2). The racial makeup of the base was 66.3% White, 23.1% African American, 0.7% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 4.3% from other races, and 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 10.4% of the population.

There were 2,748 households out of which 77.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 86.0% were married couples living together, 6.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 5.5% were non-families. 4.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 0.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.49 and the average family size was 3.60.

The age distribution was 34.9% under the age of 18, 25.5% from 18 to 24, 37.2% from 25 to 44, 2.3% from 45 to 64, and 0.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 155.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 190.3 males. These statistics are generally typical for military bases.

The median income for a household on the base was US$34,020, and the median income for a family was $33,588. Males had a median income of $26,011 versus $21,048 for females. The per capita income for the base was $12,410. About 5.8% of the population and 6.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.6% of those under the age of 18 and 100.0% of those 65 and older.

See also

References

- "U.S. Army Cadet Command and Fort Knox Leadership". Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- "General George Patton Museum of Leadership - Home". Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- "Armor School Moves Operations to Fort Benning".

- "Army cadet training to move to Fort Knox".

- "Currency & Coins: Fort Knox Bullion Depository". United States Treasury. 13 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- "9 Billion in Gold Shifted by US". The Washington Post. 5 March 1941. p. 23.

- "Cargo of Gold Stowed in Vault At Fort Knox: Armored Cars, Machine Guns Guard Transfer From Special Train". Associated Proess. 14 January 1937.

- Puleo, Stephen (2016). American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address (Kindle ed.). 9781250065742. p. 179. ISBN 9781250065742.

- Barrouquere, Brett (11 September 2013). "Fire truck damaged on 9/11 on display at Fort Knox". The Associated Press/Stars and Stripes.

- Ramage, James A., Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1986. ISBN 0-8131-1576-0.

- "Fort Knox, KY • History". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- New York Times 17 July 1903 pg 5

- The Courier-Journal 15 April 1928 end

- Stephen Puleo, American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address.

- "Rediscovering Fort Knox: Universal Military Training program comes to Fort Knox". U.S. Army.

- Sager, John (2013). "Universal Military Training and the Struggle to Define American Identity During the Cold War" (PDF). Federal History (5).

- Barth, Jack (1991). Roadside Hollywood: The emoji MovieLover's State-By-State Guide to Film Locations, Celebrity Hangouts, Celluloid Tourist Attractions, and More. Contemporary Books. Page 126. ISBN 9780809243266.

- "Gunman in Fort Knox Shooting Dies".

- "Worker at Fort Knox Kills 3, Then Shoots Himself". Associated Press. 19 October 1993 – via NYTimes.com.

- "3 Killed, 2 Hurt in Army Base Shooting Spree". latimes.

- "Shooting reported at Fort Knox military post". WKYT TV. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- M. Alex Johnson and Alastair Jamieson (3 April 2013). "'Not a random act': Civilian employee dead after Fort Knox shooting". NBCNews.com

- Dylan Lovan (4 April 2013). "FBI: Man charged with murder in Fort Knox shooting". USA Today

- Jared Feldschreiber (10 January 2014). "U.S. Army Sgt. Marquinta Jacobs Sentenced to 30 Years In Prison For Shooting Death of Lloyd Gilbert at Fort Knox" Archived 11 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Lawyer Herald

- "Human resource center opens at Fort Knox". Louisville Business First.

- "Fort Knox Partners". www.knox.army.mil. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "The Official Homepage of First Army Division East". www.first.army.mil. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "First Army - 4th Cavalry Brigade". www.first.army.mil. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- US Army. "Army announces activation of additional corps headquarters". army.mil. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "About USAMEB". goarmy.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "19th Engineer Battalion - Fort Knox, Kentucky". www.knox.army.mil. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "1st Sustainment Command (Theatre)". www.knox.army.mil. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "902d Military Intelligence Group - Fort Knox, Kentucky". www.knox.army.mil. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "The United States Army | U.S. Army Cadet Command". www.cadetcommand.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "United States Army Recruiting Command (USAREC)". www.usarec.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "100th TD (LD)". www.usar.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Aviation Command". www.usar.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "84th TNG CMD". www.usar.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "83rd USARRTC". www.usar.army.mil. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- Units & Organizations

- Kentucky – Place GCT-PH1. Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2000 Archived 12 February 2020 at Archive.today Data Set: Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data

- "US Army Armor Center- Family & Community". Archived from the original on 8 February 2008.

- "Fort Knox, Kentucky Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Knox. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Fort Knox. |

- Official website

- Fort Knox area booming

- Patton Museum, (at Fort Knox)

- Ireland Army Community Hospital, (at Fort Knox)

- Official Base information from the DOD Military Installations website

- Fort Knox Morale, Welfare, and Recreation