FokI

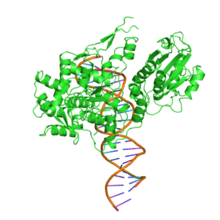

The enzyme Fok1 (Fok-1), naturally found in Flavobacterium okeanokoites, is a bacterial type IIS restriction endonuclease consisting of an N-terminal DNA-binding domain and a non-specific DNA cleavage domain at the C-terminal.[2] Once the protein is bound to duplex DNA via its DNA-binding domain at the 5'-GGATG-3' recognition site, the DNA cleavage domain is activated and cleaves, without further sequence specificity, the first strand 9 nucleotides downstream and the second strand 13 nucleotides upstream of the nearest nucleotide of the recognition site.[3]

| Restriction endonuclease Fok1, C terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Endonuc-Fok1_C | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09254 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0415 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR015334 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 2fok / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Its molecular mass is 65.4 kDa, being composed of 587 amino acids.

DNA-binding domain

The recognition domain contains three subdomains (D1, D2 and D3) that are evolutionarily related to the DNA-binding domain of the catabolite gene activator protein which contains a helix-turn-helix.[3]

DNA-cleavage domain

DNA cleavage is mediated through the non-specific cleavage domain which also includes the dimerisation surface.[4] The dimer interface is formed by the parallel helices α4 and α5 and two loops P1 and P2 of the cleavage domain.[3]

Activity

When the nuclease is unbound to DNA, the endonuclease domain is sequestered by the DNA-binding domain and is released through a conformational change in the DNA-binding domain upon binding to its recognition site. Cleavage only occurs upon dimerization, when the recognition domain is bound to its cognate site and in the presence of magnesium ions.[4]

Exploitation

The endonuclease domain of Fok1 has been used in several studies, after combination with a variety of DNA-binding domains such as the zinc finger (see zinc finger nuclease),[2] or inactive Cas9[5][6][7]

One of several human vitamin D receptor gene variants is caused by a single nucleotide polymorphism in the start codon of the gene which can be distinguished through the use of the Fok1 enzyme.[8]

References

- Aggarwal, A. K.; Wah, D. A.; Hirsch, J. A.; Dorner, L. F.; Schildkraut, I. (1997). "Structure of the multimodular endonuclease Fok1 bound to DNA". Nature. 388 (6637): 97–100. doi:10.1038/40446. PMID 9214510.

- Durai S, Mani M, Kandavelou K, Wu J, Porteus M, Chandrasegaran S (2005). "Zinc finger nucleases: custom-designed molecular scissors for genome engineering of plant and mammalian cells". Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (18): 5978–90. doi:10.1093/nar/gki912. PMC 1270952. PMID 16251401.

- Wah, D. A.; Bitinaite, J.; Schildkraut, I.; Aggarwal, A. K. (1998). "Structure of Fok1 has implications for DNA cleavage". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95 (18): 10564–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.18.10564. PMC 27934. PMID 9724743.

- Bitinaite, J.; Wah, D. A.; Aggarwal, A. K.; Schildkraut, I. (1998). "Fok1 dimerization is required for DNA cleavage". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95 (18): 10570–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.18.10570. PMC 27935. PMID 9724744.

- Tsai, S. Q. et al. (2014). Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided Fok1 nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nature Biotechnol. 32, 569–576 doi:10.1038/nbt.2908

- Guilinger, J. P., Thompson, D. B. & Liu, D. R. (2014). Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to Fok1 nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nature Biotechnol. 32, 577–582 doi:10.1038/nbt.2909

- Wyvekens, N., Topkar, V. V., Khayter, C., Joung, J. K. & Tsai, S. Q. (2015). Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided Fok1-dCas9 nucleases directed by truncated gRNAs for highly specific genome editing. Hum. Gene Ther. 26, 425–431 doi:10.1089/hum.2015.084

- Strandberg, S.; et al. (2003). "Vitamin D receptor start codon polymorphism (Fok1) is related to bone mineral density in healthy adolescent boys". J Bone Miner Metab. 21 (2): 109–13. doi:10.1007/s007740300018. PMID 12601576.