Floodlight

A floodlight is a broad-beamed, high-intensity artificial light. They are often used to illuminate outdoor playing fields while an outdoor sports event is being held during low-light conditions. More focused kinds are often used as a stage lighting instrument in live performances such as concerts and plays.

In the top tiers of many professional sports, it is a requirement for stadiums to have floodlights to allow games to be scheduled outside daylight hours. Evening or night matches may suit spectators who have work or other commitments earlier in the day, and enable television broadcasts during lucrative primetime hours. Some sports grounds which do not have permanent floodlights installed may make use of portable temporary ones instead. Many larger floodlights (see bottom picture) will have gantries for bulb changing and maintenance. These will usually be able to accommodate one or two maintenance workers.

Types

The most common type of floodlight is the metal-halide lamp, which emits a bright white light (typically 75–100 lumens/Watt). Sodium-vapor lamps are also commonly used for sporting events, as they have a very high lumen to watt ratio (typically 80–140 lumens/Watt), making them a cost-effective choice when certain lux levels must be provided.[1]

LED floodlights are bright enough to be used for illumination purposes on large sport fields. The main advantages of LEDs in this application are their lower power consumption, longer life, and instant start-up (the lack of a "warm-up" period reduces game delays after power outages).

The first LED lit sports field in the United Kingdom was switched on at Taunton Vale Sports Club on 6 September 2014. [2]

Polo

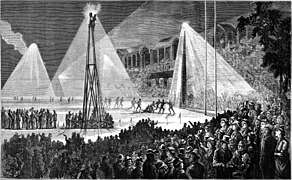

The first sport to play under floodlights was polo, on 18 July 1878. Ranelagh Club hosted a match in Fulham, London, England against the Hurlingham Club.[3]

Australian rules football

In August 1879, two matches of Australian rules football were staged at the Melbourne Cricket Ground under electric lights. The first was between two "scratch" teams composed of military personnel. The following week, two of the city's leading football clubs, rivals Carlton and Melbourne, played another night match. On both occasions, the lights failed to illuminate the whole ground, and the spectators struggled to make sense of the action in the murky conditions.

Cricket

Cricket was first played under floodlights on 11 August 1952,[4] during an exhibition game at Highbury stadium in England. International day/night cricket, played under floodlights, began in 1979. Since then, many cricket stadiums have installed floodlights and use them for both domestic and international matches. Traditional cricket floodlights are mounted at the top of a tall pole, to elevate them out of the fielder's eyeline when the ball is hit high into the air. However, some cricket stadiums have lower-mounted floodlights, particularly if the stadium is shared with other sports.

Gaelic games

Noel Walsh's advocacy was pivotal in the spread of floodlights in Gaelic games.[5] When chairman of the Munster Council, Walsh had a pilot project for floodlights at Austin Stack Park in Tralee which "became a template for every county and club ground in the country".[6]

Association football

Bramall Lane was reportedly the first stadium to host floodlit association football matches, dating as far back as 1878, when there were experimental matches at the Sheffield stadium during the dark winter afternoons. With no national grid, lights were powered by batteries and dynamoes, and were unreliable. Blackburn and Darwen also hosted floodlit matches in 1878. Thames Ironworks (who would later be re-formed as West Ham United) played a number of friendly matches under artificial light at their Hermit Road ground during their inaugural season of 1895–96. These experiments, which included high-profile fixtures against Arsenal and West Bromwich Albion, were set up using engineers and equipment from the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company.[7][8]

In 1929 the Providence Clamdiggers football club hosted the Bethlehem Steel "under the rays of powerful flood lights, an innovation in soccer" at their Providence, Rhode Island stadium.[9] On 10 May 1933, Sunderland A.F.C. played a friendly match in Paris against RC Paris under floodlights. The floodlights were fixed to overhead wires strung above and across the pitch.[10] A fresh white coloured ball was introduced after about every 20 minutes and the goalposts were painted yellow.[11]

In the 1930s, Herbert Chapman installed lights into the new West Stand at Highbury but the Football League refused to sanction their use. This situation lasted until the 1950s, when the popularity of floodlit friendlies became such that the League relented. In September 1949, South Liverpool's Holly Park ground hosted the first game in England under "permanent" floodlights: a friendly against a Nigerian XI.[12] In 1950, Southampton's stadium, The Dell, became the first ground in England to have permanent floodlighting installed. The first game played under the lights there was on 31 October 1950, in a friendly against Bournemouth & Boscombe Athletic, followed a year later by the first "official" match under floodlights, a Football Combination (reserve team) match against Tottenham Hotspur on 1 October 1951. Swindon Town became the first League side to install floodlights at The County Ground. Their first match being a friendly against Bristol City on Monday 2 April 1951. Arsenal followed five months later with the first match under the Highbury lights taking place on Wednesday 19 September 1951. The first international game under floodlights of an England game at Wembley was 30 November 1955 against Spain, England winning 4–1. The first floodlit Football League match took place at Fratton Park, Portsmouth on 22 February 1956 between Portsmouth and Newcastle United.[13]

Many clubs have taken their floodlights down and replaced them with new ones along the roof line of the stands. This previously had not been possible as many grounds comprised open terraces and roof lines on covered stands were too low. Elland Road, Old Trafford and Anfield were the first major grounds to do this in the early 1990s. Deepdale, The Galpharm Stadium and the JJB Stadium have since been built with traditional floodlights on pylons.

Rugby league

The first rugby league match to be played under floodlights was on 14 December 1932 when Wigan met Leeds in an exhibition match played at White City Stadium in London (8pm kick off).[14] Leeds won 18–9 in front of a crowd of over 10,000 spectators. The venture was such a success that the owners of the White City Ground took over the "Wigan Highfield" club and moved them to play Rugby League games at the ground under floodlights the following season, with most of their matches kicking off on Wednesday Nights at 8pm. That venture only lasted one season before the club moved back up north.

The first floodlit match for rugby league played in the heartlands was on 31 October 1951 at Odsal Stadium, Bradford when Bradford Northern played New Zealand in front of 29,072.[15]

For a club to play in the Super League they must have a ground with floodlights adequate for playing a professional game.

See also

References

- "edisontechcenter.org/SodiumLamps". edisontechcenter.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Inglis, Simon (2014). Played in London. Swindon: English Heritage. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84802-057-3.

- "Let there be light". cricinfo.com. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Barry, Stephen (29 April 2020). "Champion of Clare football Noel Walsh has died". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

He was chairman of the GAA's Football Development Committee, championed the merits of the Railway Cup, and promoted the spread of floodlights to GAA grounds.

- O Muircheartaigh, Joe (2 May 2020). "Noel Walsh: Farewell to a driver of change and fairness". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Powles, John (29 June 2017). "The amazing story of West Ham United's first home ground". West Ham United F.C. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Tongue, Steve (2016). Turf Wars: A History of London Football. Pitch Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-78531-248-9.

- "Draw with Providence in Night Soccer game". Bethlehem Steel Soccer. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Lanchberry, Edward (1950). Footballer’s Progress: Raich Carter. Sporting Handbooks Ltd. p. 183.

- Garrick, Frank (2003). Raich Carter The Biography. SportsBooks Limited. p. 34. ISBN 1 899807 18 7.

- Jawad, Hyder; "Rest In Pieces: South Liverpool FC, 1894-1994 (2014)", p234

- "The History Of The Football League". The Football League. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- "The History Of Rugby League". Rugby League Information. napit.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "Timeline of events at Odsal stadium" (PDF). Past Times the social history of Odsal stadium project. Bradford Bulls Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2011.