First Syrian Republic

The First Syrian Republic,[2][lower-alpha 1] officially the Syrian Republic,[lower-alpha 2] was formed in 1930 as a component of the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon, succeeding the State of Syria. A treaty of independence was made in 1936 to grant independence to Syria and end official French rule, but the French parliament refused to accept the agreement. From 1940 to 1941, the Syrian Republic was under the control of Vichy France, and after the Allied invasion in 1941 gradually went on the path towards independence. The proclamation of independence took place in 1944, but only in October 1945 Syrian Republic was de jure recognized by the United Nations; it became a de facto sovereign state on 17 April 1946, with the withdrawal of French troops. It was succeeded by the Second Syrian Republic upon the adoption of a new constitution on 5 September 1950.[4]

Syrian Republic | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930–1950 | |||||||||||||||

.svg.png) .svg.png) | |||||||||||||||

Territory of the Syrian Republic as proposed in the unratified Franco-Syrian Treaty of 1936. (Lebanon was not part of the plan). In 1938, Alexandretta was also excluded. | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Component of the Mandate of Syria and the Lebanon (1930–1946) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Damascus | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic French Syriac Armenian Kurdish Turkish | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (all branches incl. Alawite) Christianity Judaism Druzism Yezidism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | French Mandate (1930–1946) Parliamentary republic (1946–1950) | ||||||||||||||

| High Commissioner (1930-1946) | |||||||||||||||

• 1930–1933 (first) | Auguste Ponsot | ||||||||||||||

• 1944–1946 (last) | Étienne Beynet | ||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||

• 1932–1936 (first) | Muhammad Ali al-Abid | ||||||||||||||

• 1945–1949 (last) | Shukri al-Quwatli | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||

• 1932–1934 | Haqqi al-Azm (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1950 (last) | Nazim al-Kudsi | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | 20th century | ||||||||||||||

• Republic formed | 14 May 1930 | ||||||||||||||

• Treaty of Independence | 9 September 1936 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 September 1938 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 October 1945 | |||||||||||||||

• Withdrawal of French troops | 17 April 1946 | ||||||||||||||

• new constitution adopted | 5 September 1950 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1938 | 189,880 km2 (73,310 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1938 | 2,721,379 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Syrian pound | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | SY | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

French Mandate prior to the Franco–Syrian Treaty of Independence

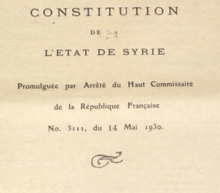

The project of a new constitution was discussed by a Constituent Assembly elected in April 1928, but as the pro-independence National Bloc had won a majority and insisted on the insertion of several articles "that did not preserve the prerogatives of the mandatary power", the Assembly was dissolved on August 9, 1928. On May 14, 1930, the State of Syria was declared the Republic of Syria and a new Syrian constitution was promulgated by the French High Commissioner, in the same time as the Lebanese Constitution, the Règlement du Sandjak d'Alexandrette, the Statute of the Alawi Government, the Statute of the Jabal Druze State.[5] A new flag was also mentioned in this constitution:

- The Syrian flag shall be composed as follows, the length shall be double the height. It shall contain three bands of equal dimensions, the upper band being green, the middle band white, and the lower band black. The white portion shall bear three red stars in line, having five points each.[6][7]

During December 1931 and January 1932, the first elections under the new constitution were held, under an electoral law providing for "the representation of religious minorities" as imposed by article 37 of the constitution.[7] The National Bloc was in the minority in the new Chamber of deputies with only 16 deputies out of 70, due to intensive vote-rigging by the French authorities.[8] Among the deputies were also three members of the Syrian Kurdish nationalist Xoybûn (Khoyboun) party, Khalil bey Ibn Ibrahim Pacha (Al-Jazira Province), Mustafa bey Ibn Shahin (Jarabulus) and Hassan Aouni (Kurd Dagh).[9] There were later in the year, from March 30 to April 6, "complementary elections".[10]

In 1933, France attempted to impose a treaty of independence heavily prejudiced in favor of France. It promised gradual independence but kept the Syrian Mountains under French control. The Syrian head of state at the time was a French puppet, Muhammad 'Ali Bay al-'Abid. Fierce opposition to this treaty was spearheaded by senior nationalist and parliamentarian Hashim al-Atassi, who called for a 60-day strike in protest. Atassi's political coalition, the National Bloc, mobilized massive popular support for his call. Riots and demonstrations raged, and the economy came to a standstill.

Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence

After negotiations in March with Damien de Martel, the French High Commissioner in Syria, Hashim al-Atassi went to Paris heading a senior Bloc delegation. The new Popular Front-led French government, formed in June 1936 after the April–May elections, had agreed to recognize the National Bloc as the sole legitimate representatives of the Syrian people and invited al-Atassi to independence negotiations. The resulting treaty called for immediate recognition of Syrian independence as a sovereign republic, with full emancipation granted gradually over a 25-year period.

In 1936, the Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence was signed, a treaty that would not be ratified by the French legislature. However, the treaty allowed Jabal Druze, the Alawite region (now called Latakia), and Alexandretta to be incorporated into the Syrian republic within the following two years. Greater Lebanon (now the Lebanese Republic) was the only state that did not join the Syrian Republic. Hashim al-Atassi, who was Prime Minister during King Faisal's brief reign (1918–1920), was the first president to be elected under a new constitution adopted after the independence treaty.

The treaty guaranteed incorporation of previously autonomous Druze and Alawite regions into Greater Syria, but not Lebanon, with which France signed a similar treaty in November. The treaty also promised curtailment of French intervention in Syrian domestic affairs as well as a reduction of French troops, personnel and military bases in Syria. In return, Syria pledged to support France in times of war, including the use of its air space, and to allow France to maintain two military bases on Syrian territory. Other political, economic and cultural provisions were included.

Atassi returned to Syria in triumph on September 27, 1936 and was elected President of the Republic in November.

In September 1938, France again separated the Syrian Sanjak of Alexandretta and transformed it into the State of Hatay. The State of Hatay joined Turkey in the following year, in June 1939. Syria did not recognize the incorporation of Hatay into Turkey and the issue is still disputed until the present time.

The emerging threat of Adolf Hitler induced a fear of being outflanked by Nazi Germany if France relinquished its colonies in the Middle East. That, coupled with lingering imperialist inclinations in some levels of the French government, led France to reconsider its promises and refuse to ratify the treaty. Also, France ceded the Sanjak of Alexandretta, whose territory was guaranteed as part of Syria in the treaty, to Turkey. Riots again broke out, Atassi resigned, and Syrian independence was deferred until after World War II.

World War II and aftermath

With the fall of France in 1940 during World War II, Syria came under the control of the Vichy Government until the British and Free French invaded and occupied the country in July 1941. Syria proclaimed its independence again in 1941 but it was not until 1 January 1944 that it was recognized as an independent republic.

In the 1940s, Britain secretly advocated the creation of a Greater Syrian state that would secure Britain preferential status in military, economic and cultural matters, in return for putting a complete halt to Jewish ambition in Palestine. France and the United States opposed British hegemony in the region, which eventually led to the creation of Israel.[11]

On 27 September 1941, France proclaimed, by virtue of, and within the framework of the Mandate, the independence and sovereignty of the Syrian State. The proclamation said "the independence and sovereignty of Syria and Lebanon will not affect the juridical situation as it results from the Mandate Act. Indeed, this situation could be changed only with the agreement of the Council of the League of Nations, with the consent of the Government of the United States, a signatory of the Franco-American Convention of April 4, 1924, and only after the conclusion between the French Government and the Syrian and Lebanese Governments of treaties duly ratified in accordance with the laws of the French Republic.[12]

Benqt Broms said that it was important to note that there were several founding members of the United Nations whose statehood was doubtful at the time of the San Francisco Conference and that the Government of France still considered Syria and Lebanon to be mandates.[13]

Duncan Hall said "Thus, the Syrian mandate may be said to have been terminated without any formal action on the part of the League or its successor. The mandate was terminated by the declaration of the mandatory power, and of the new states themselves, of their independence, followed by a process of piecemeal unconditional recognition by other powers, culminating in formal admission to the United Nations. Article 78 of the Charter ended the status of tutelage for any member state: 'The trusteeship system shall not apply to territories which have become Members of the United Nations, relationship among which shall be based on respect for the principle of sovereign equality.'"[14] So when the UN officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, after ratification of the United Nations Charter by the five permanent members, as both Syria and Lebanon were founding member states, the French mandate for both was legally terminated on that date and full independence attained.[15]

On 29 May 1945, France bombed Damascus and tried to arrest its democratically elected leaders. While French planes were bombing Damascus, Prime Minister Faris al-Khoury was at the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco, presenting Syria's claim for independence from the French Mandate.

Independence

Syrian independence was de jure attained on 24 October 1945. Continuing pressure from Syrian nationalist groups and British pressure forced the French to evacuate their last troops on 17 April 1946.

Notes

References

- www.nationalanthems.info

- Karim Atassi (2018). Syria, the Strength of an Idea. p. 179.

- العرب والعروبة: من القرن الثالث حتى القرن الرابع عشر الهجري. 1959. p. 668.

- George Meri Haddad (1971). Revolutions and Military Rule in the Middle East. 2. Robert Speller & Sons. p. 286.

- Youssef Takla, "Corpus juris du Mandat français", in: Méouchy, Nadine; Sluglet, Peter, eds. (2004). The British and French Mandates in Comparative Perspectives (in French). Brill. p. 91. ISBN 978-90-04-13313-6. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- "French: Art. 4 – Le drapeau syrien est disposé de la façon suivante: Sa longueur est le double de sa hauteur. Il comprend trois bandes de mêmes dimensions. La bande supérieure est verte, la médiane blanche, l’inférieure noire. La partie blanche comprend trois étoiles rouges alignées à cinq branches chacune.", article 4 of the Constitution de l'Etat de Syrie, 14 May 1930

- The 1930 Constitution is integrally reproduced in: Giannini, A. (1931). "Le costituzioni degli stati del vicino oriente" (in French). Istituto per l’Oriente. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- Mardam Bey, Salma (1994). La Syrie et la France: bilan d'une équivoque, 1939-1945 (in French). Paris: Editions L'Harmattan. p. 22. ISBN 9782738425379. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Tachjian, Vahé (2004). La France en Cilicie et en Haute-Mésopotamie: aux confins de la Turquie, de la Syrie et de l'Irak, 1919-1933 (in French). Paris: Editions Karthala. p. 354. ISBN 978-2-84586-441-2. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Tejel Gorgas, Jordi (2007). Le mouvement kurde de Turquie en exil: continuités et discontinuités du nationalisme kurde sous le mandat français en Syrie et au Liban (1925-1946) (in French). Peter Lang. p. 352. ISBN 978-3-03911-209-8. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- https://www.haaretz.co.il/hasen/spages/950373.html

- See Foreign relations of the United States diplomatic papers, 1941. The British Commonwealth; the Near East and Africa Volume III (1941), pages 809-810; and Statement of General de Gaulle of November 29, 1941, concerning the Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, Marjorie M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1963) 680-681

- See International law: achievements and prospects, by Mohammed Bedjaoui, UNESCO, Martinus Nijhoff; 1991, ISBN 92-3-102716-6, page 46

- Mandates, Dependencies and Trusteeship, by H. Duncan Hall, Carnegie Endowment, 1948, pages 265-266

- "History of the United Nations". United Nations.