First Chilean Navy Squadron

The First Chilean Navy Squadron was the heterogeneous naval force that temporarily terminated Spanish colonial rule in the Pacific and protagonized the most important naval actions of in the Latin American wars of independence.[1] The Chilean revolutionary government organized the squadron in order to carry the war to the Viceroyalty of Perú, then the center of Spanish power in South America, and thus secure the independence of Chile and Argentina.

| First Chilean Navy Squadron | |

|---|---|

| Primera Escuadra Nacional de Chile | |

Departure of the First Chilean Navy Squadron on 9 October 1818, Thomas Somerscales | |

| Active | 1817–1826 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval warfare |

| Engagements | Spanish American wars of independence |

| Commanders | |

| Supreme commander | Bernardo O'Higgins Ramón Freire |

| Fleet commander | Manuel Encalada Thomas Cochrane |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |  |

Background

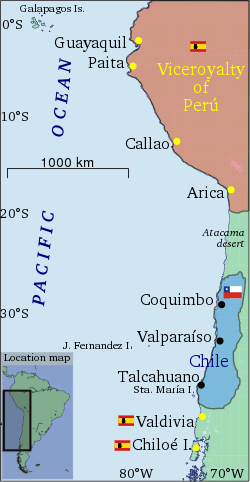

The Napoleonic wars (1803–1815) had crippled Spain's navy, and the French occupation had destroyed the logistical base of its dockyards, with the result of the loss of the majority of Spain's navy. Nevertheless, during the Patria Vieja (Old Fatherland) period, the Spaniards and the Royalists of Chile and Peru were able from Callao, the royalist stronghold in Perú, to blockade any Chilean revolutionary ports, to land in Talcahuano, a loyal port, and support the advance of the royalist troops of Chile against Santiago de Chile, the main city of the revolutionary forces and crush the rebellion in Chile. Argentine historian Bartolomé Mitre gives the following list[2] of armed Spanish ships in the west coast of South America, but it was never done simultaneously: frigates Venganza (44 guns) and Esmeralda (44), merchant corvettes Milagro (18), San Juan Bautista (18) and Begoña (18), second class frigates Governadora (16), Comercio (12), Presidente (12), Castilla (12) and Bigarrera (12), corvettes Resolución (34), Sebastiana (34) and Veloz (22), brigantine Pezuela (18), plus other 3 unnamed ships with 37 guns. All things considered 17 ships with 331 guns along the war. In 1819 came the frigate Prueba and 1824 came the 74 guns Asia and the Aquiles.

Naval capacity played almost no role for the revolutionary forces in the time from the first declaration of independence 1810 to the Spanish "reconquest" of Chile 1814. Two ships bought by the patriots were defeated in a short fight off Valparaíso in May 1813.[3](p9)

After the argentinians and Chilean insurgency won the Battle of Chacabuco (1817), the beginning of the Patria Nueva (New Fatherland), Chilean patriots re-entered Santiago, but Talcahuano and Concepción (until 1819-20), Valdivia (until 1820) and Chiloé (until 1826) remained under Chilean royalist control.

The Chilean patriots decided that they needed their own navy with trustworthy crews if they were to protect the long coasts of the state and to mobilize troops against the enemy. Without a proper naval force, Chile was vulnerable to enemy landings.

The major concern of the British and US governments was the colonial dispute and preservation of their trade. During the Napoleonic wars Britain became committed to defending the status quo in the peninsular Spain in order to ensure Spain's alliance against France. In 1817, Castlereagh secured an order forbidding British subjects from serving in Spanish American armies.[4] Although, in practice, strict neutrality was not always observed.[5]:29

Still, British and US public opinion welcomed the end of Spanish autocratic government in South America. In England, the end of the Napoleonic wars permitted the government to reduce the number of ships in the Royal Navy from 700 to 134 and the number of sailors from 140,000 to 23,000, thus lessening the presence of the Royal Navy off the coasts of South America.[6](p19)

1817-1818

Build up

After the Battle of Chacabuco, Bernardo O'Higgins remarked that "this triumph and a hundred more will be insignificant if we do not control the sea". Consequently, the Chilean government, led by O'Higgins, on 20 November 1817 authorized privateers to engage as commerce raiders, interrupting the Spanish trade off the west coast of South America.[7] Although Spanish commerce along the whole coast from Chile to Panama was interrupted, the military and naval achievements of the privateers were insignificant.

But they also violated the rights of neutral vessels. They drew to their crews navy deserters, so that O'Higgins was eventually forced to put a limit to their excesses.[8]

| Shipname | Type | tonnage | Other names | Year | Property of | Guns | Prizes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santiago Bueras (1817) | Brigantine | 200.0 | Lancaster | 1817 | Gregorio Cordovéz | 12 | Los Ángeles, Resolución | [9] |

| El Chileno (1817) | Brigantine | Adeline | 1817 | Felipe S. de Solar | 12 | Saetas, Diamante, Inspectora, Balero and San Antonio | [10] | |

| La Fortuna (1817) | Boat | 20 | Death or Glory | 1817 | Budge and MacKay | Minerva | [11] | |

| La Fortuna (1817) | Schooner | 180.0 | Catalina | MacKay | 10 | San Miguel and Gran Poder | [12] | |

| Minerva (1817) | Boat | 1817 | Budge and MacKay | 12 | Santa María | [13] | ||

| Maipú (1818) | Brigantine | 1818 | José M. Manterola | San Antonio, Lanzafuego Providencia, Buena Esperanza | [14] | |||

| Congreso (1817) | Schooner | 1818 | J.A. Turner | Empecinado, Golondrina, San Pedro Regalado | [15] | |||

| Nuestra Señora del Carmen (1818) | Schooner | Better known as Furioso | 1818 | Manuel Antonio Boza | 1 | Nuestra Señora de Dolores,Machete | [16] | |

| Rosa de los Andes (1818) | Corvette | 400.0 | Rose | 1819 | 36 | Tres Hermanas | [17] | |

| Coquimbo (1818)[18] | Avon later Chacabuco (1818) | 1818 |

O'Higgins set out to create a navy out of nothing. José Ignacio Zenteno was nominated as Minister of Marine and promulgated in November 1817 the Reglamento General de Marina, a legal framework for the new institution. José Antonio Álvarez Condarco and Manuel Hermanegildo Aguirre were sent to respectively to London and New York City to recruit men and to acquire warships.[19]

A few days after the Battle of Chacabuco, Chilean revolutionaries commissioned their first ship, the old US-smuggler ship Eagle, once captured by the Spaniards and now in the hand of the Chileans.[20] Eagle was first renamed Águila and then later Pueyrredón. The regular Chilean navy began to grow steadily and soon was able to man the East Indiaman Windham, which arrived at Valparaíso in March 1818, and Cumberland, which arrived at Valparaíso in May 1818. The Chileans had bought both in England and renamed and Lautaro and San Martín. In July 1818 the Columbus, a US-origin 18-gun brig, reached Valparaíso and was bought and renamed Araucano.

As usual at the time all prizes and seized property was subject to rules defining shares and differences between property and ships captured afloat or in transit, or property on land.[6](p81)

| Ship name | Type | tonnage[21] | Other names | Commissioned | from | Price |

| Águila | Brigantine | 220 | Eagle | 1817.02 | Spanish prize | |

| Lautaro | East Indiaman | 850 | Windham | 1818.03 | bought in London | $180,000 |

| San Martín | East Indiaman | 1300 | Cumberland | 1818.05 | bought in London | $140,000 |

| Chacabuco | Corvette[22](p59) | 450[23] | Coquimbo, before Avon | 1818.06 | bought from Chilean privateer | $36.000 |

| Araucano[6](p20) | Brigantine | 270 | Columbus | 1818.06 | bought in USA | $33,000 |

| Galvarino[22] | brig-sloop | 398 | HMS Hecate (1809) Lucy[21] |

1818.10 | bought in London | $70,000[22](p416) |

| O'Higgins | Frigate | 1220 | Patrikii (Russia) María Isabel (Spain) |

1818.10 | Spanish prize | |

| Moctezuma | Sloop | 200 | 1819.02 | Spanish prize | ||

| Independencia[6](p20) | Corvette | 700 | Curatio | 1819.06 | bought in USA | USD300.000[19] |

Note: $100,000 was equivalent to £20,000[24]

The rescue from the Juan Fernández Island

The first task of the Águila was to bring home 72 patriots being held prisoner in the Juan Fernández Islands. This apparently simple task had an enormous importance: among the rescued were Juan Enrique Rosales, Agustín de Eyzaguirre, Ignacio Carrera, Martín Calvo Encalada, Francisco Antonio Pérez, Francisco de la Lastra, José Santiago Portales, members of the first revolutionary governments; Manuel de Salas, (author of the Freedom of wombs law that banned Slavery in Chile in 1811), Juan Egaña, co-author of the first constitution of Chile, Mariano Egaña (main writer of the Chilean Constitution of 1833), Joaquín Larraín and José Ignacio Cienfuegos, churchmen of the insurgents; Luis de la Cruz, Manuel Blanco Encalada and Pedro Victoriano, eminent military men.[5]

Later, the Aguila joined Lautaro to break the blockade of Valparaíso by the Spanish vessel Esmeralda.

Summer 1818-1819

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe encouraged the Fernando VII's restored (in 1814) autocracy to make every effort to retain their American colonies. They planned in October 1817 to send 12,000 men to Buenos Aires and 2,000 to Chile to repress the independent movements in South America. But the Manila Galleons and tax revenues from the Spanish Empire had been interrupted. Spain was all but bankrupt and its government was unstable.

On 21 May 1818 eleven Spanish ships set sail from Cádiz escorted by the Spanish frigate Reina María Isabel bound for Talcahuano, a Chilean port still in possession of Spanish King. One of the ships remained in Tenerife. According to Antonio García Reyes in Memoria sobre la Primera Escuadra Nacional[25] the transporter were: Rosalía (Escorpión), Trinidad, Especulación, Dolores, Javiera (Jerezana), Magdalena, Carlota, San Fernando, Mocha (Atocha) and Elena (in brackets the names given by Diego Barros Arana in his Historia General de Chile). This expedition was called "Expedición de la Mar del Sur" in Spain.

The eleven transport carried food supplies, ammunition, guns and, more importantly, two infantry battalions of the Cantabria Regiment, three cavalry squadrons, two artillery and combat engineer companies, for a total of 2,080 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Fausto del Hoyo,[6](p13) actually a member of the constitutionalist party in Spain.[5]:23 The naval force was under command of Captain Manuel del Castillo, but suffering from a paralytic stroke, he had to disembark in Tenerife and the command was transferred to Lieutenant Dionisio Capaz.

During the voyage the crew of one transport was severely weakened by sickness and at 5°N latitude the soldiers disembarked in Trinidad where they mutinied, executed their officers, deserted the fleet and sailed to Buenos Aires where they surrendered to the revolutionary authorities on 16 August 1818 and handed over orders, signals and rendezvous points of the expedition. The Argentine Government sent a hot-foot courier over the Andes with the information to warn the Government in Santiago de Chile.

The capture of the Spanish frigate María Isabel

| Shipname | tons | guns | men | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Martin | 1300 | 60 | 492 | Guillermo Wilkinson |

| Lautaro | 850 | 46 | 253 | Charles Wooster |

| Chacabuco | 450 | 20 | 134 | Francisco Diaz |

| Araucano | 270 | 16 | 110 | Raymond Morris |

| total | 2870 | 142 | 1109 | |

| Commander-in-Chief: Manuel Blanco Encalada | ||||

On 19 October 1818, under the rebellion of Spanish expeditionary forces, who goes to Buenos Aires and change the side, the first commander of the Chilean Squadron, Manuel Blanco Encalada, was ordered to set sail with San Martín, Lautaro, Chacabuco and Araucano in order to intercept the rest of Spanish convoy. Later Galvarino and Intrépido (an Argentine ship) joint the flotilla off Talcahuano. On 28 October they found the Reina María Isabel at anchor in Talcahuano. The crew of the Reina María Isabel ran their vessel aground to render her useless to the Chileans, but they were able to take the frigate in a brisk action and to repair the damage. With the Spanish prize the squadron sailed to Santa María Island, approximately 30 km south of Talcahuano, where they stayed for a week until, one by one, the Spanish transports[25] Magdalena, Dolores, Carlota, Rosalia and Elena sailed innocently into their arms. Only four Spanish transports could disembark Captain Fausto del Hoyo and 500 men in Talcahuano and continue to Callao.

The Reina Maria Isabel was renamed O'Higgins and added to the Chilean Squadron. With the loss of the Reina Maria Isabel, control of the sea passed to the insurgents, making the invasion of Peru itself an imminent danger.

Thomas Cochrane and the heterogeneity of the crew

Under command of Lord Cochrane, the majority of the officers and sailors in the new Chilean Navy were from Britain.[note 1]

In the middle of 1818, Bernardo O'Higgins, through his agent in London, had recruited Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald, a daring and successful captain of the Napoleonic Wars with well-known radical views to take command of the recently created Chilean Navy. Cochrane arrived in Valparaiso in December 1818, became a Chilean citizen of unrecognized state, was appointed vice admiral, and took command with pay and allowances of £1200[6](p38) a year.

O'Higgins founded the first Squadron of Chile on November 20, 1817. Indeed, one of the characteristics of the first squad was the heterogeneity of its crew, consisting mainly of two large groups: those who spoke English and those who spoke Spanish.[26] It was stipulated that each ship should be governed by the language of its commander.[27]

As of November 1818, being commanded by Lord Thomas Cochrane, which meant that approximately 500 British, including sailors and officers, were integrated with him. Cochrane distrusted the Chilean officiality, so that upon his arrival he removed all the Chilean commanders and replaced them by British officers or Americans. In this way, in practice, the first Chilean squadron officially governed by the English language, to the point that an officer of the British Royal Navy said that "even the uniform is very similar to ours." [28]

Cochrane was the first vice admiral of Chile. He reorganized the Chilean navy, introducing British naval customs and English language officially. Once Cochrane took command of the squadron, there emerged a new difficulty: what regulation or standard to use on ships. The British were governed by the British Regulations and the Chileans by the Spain Ordinances. The majority of commanders were of British origin so, in practice, British regulations on the ship under a British captain. The organization of the squadron was complete in January 1819, and the government was able to recruit 1,400 of the 1,610 officers and men it needed. Two-thirds of the seamen and almost all the officers were British or North-Americans.[29]

First blockade of Callao

On 14 January 1819 the squadron O'Higgins, Lautaro, Chacabuco, and San Martín set sails for the first blockade of Callao. The orders were specific and detailed: to blockade the port of Callao, to cut off the maritime forces of the enemy, and 17 other missions. A second Flotilla Galvarino (Cap. Spry), Aguila (Cap.Prunier) and the Araucano (Cap.Ramsay) followed in March under the command of Manuel Blanco Encalada. The Real Felipe Fortress was a striking fort built to protect the city against pirate attacks. Only the Baluarte del Rey had 24 iron and 8 bronze guns.

The expedition freed 29 Chilean soldiers imprisoned in the San Lorenzo Island, seized ships (best prizes were Moctezuma and Victoria), property, money, gold and silver, but the massive batteries and Spanish passive system of defence (see map: a Baluarte de la Reina, b Baluarte del Rey, c Baluarte del Príncipe, d Baluarte de San José, e Baluarte de San Felipe) and the refusal of their warships to come out of Callao and fight frustrated further success. On 1 June the squadron arrived at Valparaíso from the first expedition to Callao.

| Shipname | Officers | Abroad crew | Chilean crew | Ship boys | Artill- erists | Marine Infantry | Total crew | Guns | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O'Higgins | 7 | 47 | 94 | 45 | 20 | 70 | 283 | 48 | Robert Forters |

| San Martín | 8 | 102 | 169 | 35 | 73 | 69 | 456 | 52 | Guillermo Wilkinson |

| Lautaro | 9 | 109 | 80 | 27 | 25 | 38 | 282 | 48 | Martin Guise |

| Chacabuco | 7 | 6 | 78 | 18 | 109 | 20 | Thomas Carter | ||

| Total | 31 | 264 | 421 | 107 | 118 | 195 | 1130 | 168 | |

| Commander-in-Chief: Lord Thomas Cochrane | |||||||||

Summer 1819-1820

On 11 May 1819 the King of Spain had dispatched a new expedition to the West Coast of America under the command of Rosendo Porlier, who was to replace the naval chief of Callao Antonio Vacaro. Two poorly provisioned ships of the line San Telmo (74 guns) and Alejandro I (74 guns, formerly a Russian ship), the frigate Prueba (34 guns) and the transport Mariana sailed from Cádiz bound to Callao.

Second blockade of Callao

On 12 December 1819, the squadron set sails to renew the attack on the Viceroyalty of Perú. The orders were:

- to secure the command of the Pacific

- to find and destroy the second Spanish convoy

- to attack Callao with Congreve rockets

- any hostility against Peruvian persons or properties was forbidden

The cost of the expedition for the Chilean state was no less than £80,000.[6](p60)

As Cochrane found that the forts of Callao had been reinforced and the element of surprise had been lost, he was convinced that further attacks would be doomed to failure.

A successful campaign was frustrated, in part due to the death of Colonel Charles and the failure of the Congreve rockets.

But the Spanish reinforcements sent from Cádiz had shrunk to a fraction of its original size. The Alejandro I had to turn back to Spain because of its leaky condition and the San Telmo was lost in a severe storm rounding Cape Horn with 644 men. Only the transport Mariana (on 9 October) and the frigate Prueba (on 2 October) reached Callao but, the frigate fled to Guayaquil under pursuit by the Chileans.

Capture of Valdivia

After failing to capture the Spanish fortress of Real Felipe in Callao, in defiance of his orders and without even telling the Chilean authorities what he intended to do, Thomas Cochrane decided to assault the city of Valdivia, the most fortified place in southern Chile at the time.[30] Valdivia was a threat to Chilean independence as it was a stronghold and supply base for Spanish troops and was the first landing site for ships coming from Spain after the voyage round Cape Horn. Valdivia provided a safe landing site for sending reinforcements to the loyalist guerrilla fighting the Guerra a muerte in the area of La Frontera.

Valdivia was isolated from the rest of Chile by native Mapuche territory, and the only entrance to Valdivia was via the mouth of Valdivia River; Corral Bay. The bay was fortified with several forts built to prevent pirate raids or any attack from a foreign nation.

The forts of Valdivia were captured on 3 and 4 February 1820, and their fall effectively ended the last vestiges of Spanish power in mainland Chile and put large amounts of military materiel in the Chilean hands: 50 tons gunpowder, 10,000 cannon shot, 170,000 musket balls, small arms, 128 pieces of artillery, and the Dolores. The Chilean Intrépido was lost.

Summer 1820-1821

Freedom Expedition of Perú

The emancipation of Perú was to have been a common enterprise by Chile and Argentina.[31] Argentina, then a loose alliance of provinces, distracted by internal strife and another threat of invasion from Spain was unable to contribute for the expedition and ordered José de San Martín back to Argentina. San Martín choose to disobey (see Acta de Rancagua) and O'Higgins decided that Chile would assume the costs of the Freedom Expedition of Perú.[32](p39)

On 20 August 1820 the expedition sailed from Valparaíso for Paracas, near Pisco in Perú. The escort was provided by the squadron and comprised the flagship O'Higgins (under Captain Thomas Sackville Crosbie), frigate San Martín (Captain William Wilkinson), frigate Lautaro (Captain Martin Guise), the corvette Independencia (Captain Robert Forster), the brigs Galvarino (Captain John Tooker Spry), Araucano (Captain Thomas Carter), and Pueyrredón (Lieutenant William Prunier) and the schooner Moctezuma (Lieutenant George Young).[6](p98)

Every expeditionary ship got a painted number so that it could be identified at a distance. There are discrepancies between authors about the names and number and some names of the transports.[33]

| Ship name | Ship number | tons | Other names | troops | personnel or cargo |

| Potrillo[Notes 1] | 20 | 180 | 0 | 1400 boxes of munitions for the infantry and artillery, 190 boxes of munitions for flamethrowers, and 8 barrels powder | |

| Consecuencia | 11 | 550 | Argentina | 561 | |

| Gaditana | 10 | 250 | 236 | 6 guns | |

| Emprendedora | 12 | 325 | Empresa | 319 | 1280 boxes musket balls, 1500 boxes supplies of tools and repair shop |

| Golondrina | 19 | 120 | 0 | 100 boxes munitions, 190 boxes clothes, 460 sack kekse, 670 bunches jerked beef | |

| Peruana | 18 | 250 | 53 | hospital, physicians and 200 boxes | |

| Jerezana | 15 | 350 | 461 | ||

| Minerva | 8 | 325 | 630 | ||

| Águila[Notes 1] | 14 | 800 | not Brigantine Pueyrredón |

752 | 7 guns |

| Dolores[Notes 1] | 9 | 400 | 395 | ||

| Mackenna | ? | 500 | 0 | 960 boxes with weapons, armor and leather goods for infantry and cavalry. 180 quintal iron pieces | |

| Perla | 16 | 350 | 140 | 6 guns | |

| Santa Rosa | 13 | 240 | Santa Rosa de Chacabuco or Chacabuco |

372 | 6 guns |

| Nancy | 21 | 200 | 0 | 80 horses and fodder | |

Notes

- Property of Thomas Cochrane, hired out to Chile, Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, page 144

.jpg)

On 8 September 1820 the liberating army disembarked 100 miles southeast of Lima: 4118 soldiers, 4000 of them were Chileans.[22](p144) On the night of 5 November Cochrane and 240 volunteers wearing white with blue armbands captured the Spanish frigate Esmeralda (1791) within the port of Callao. She was renamed Valdivia and commissioned to the Chilean Navy.

Perú was not seen as an enemy territory but was occupied by Spanish military forces. The commander of the expeditionary troops José de San Martín understand that the task was to neutralise the Spanish army so that the population could liberate themselves and he followed a slow and relentless course.

1821-1822

Cochrane sails to California

In July 1821 the liberation troops entered Lima, declared Perú's independence, and San Martín was acclaimed as Protector of the new state, and Cochrane considered him (San Martín) relieved as Commander of the Expedition. However, undefeated Spanish troops still occupied the highlands. Cochrane clashed with the cautious San Martín because of the unrealistic hope for a national rising in support of Peruvian independence and San Martín's commanders were disenchanted about his inaction.

Although San Martín set about raising the bonuses he had promised the fleet after the fall of Lima, he refused to pay its routine expenses or prize money for the Esmeralda which he regarded as the responsibility of the Chilean government. Cochrane was furious and, when the Peruvian Treasury and the contents of the mint were loaded onto the schooner Sacramento to avoid an advance by the Spanish army from the interior, Cochrane seized the ship on 14 September and took the money. The amount seized was, according to Peruvian sources, £80,000 or $400,000.[34]

Now in violent conflict with San Martin, on 6 October 1821 Cochrane sailed with the Araucano, O'Higgins, Valdivia, Independencia and the schooner Mercedes in order to scour the Pacific for the last remnants of the Spanish Navy, the frigates Venganza and Prueba. After a month in Guayaquil to refit and to reprovision the ships, the squadron searched the West Coast of the Americas as far north as Loreto, Baja California Sur, where the Araucano was lost to mutineers.

After a pursuit of five months, he blockaded the Spanish ships in the port of Guayaquil. They surrendered to the authorities of the port.

The O'Higgins and Valdivia anchored in Valparaiso on 2 June 1822.

Cochrane left the service of the Chilean Navy on 29 November 1822.

Capture of Chiloé in 1825

In 1825 a squadron commanded by Manuel Blanco Encalada landed 2,575[35] troops under the command of Ramón Freire on Chiloé and then blockaded the island. The Royalists on the island, the last bastion of Spain in South America, surrendered on 12 January 1826.

| Ships name | Captain |

|---|---|

| O'Higgins (Ex-Maria Isabel) | Blanco Encalada |

| Independencia | M.Cobett |

| Aquiles | Wooster |

| Galvarino | Wiater |

| Chacabuco | Carlos Garcia del Postigo |

| Lautaro (as Transporter) | Guillermo Bell |

| Resolucion | Manuel Garcia |

| Ceres | |

| Infatigable | |

| Swallow (Golondrina English ship) | Kierulf |

Decommissioning of the Squadron

In April 1826 O'Higgins's successor, Ramón Freire, reduced the active navy to a single brig. He decommissioned the rest of the navy and sold O'Higgins and Chacabuco to Argentina.

Aftermath

Chile's financial effort, burdened with the squadron and the expedition to Perú impoverished the country. Even O'Higgins and his ministers had not been paid for months.[6](p168) As a partial result of the Latin wars of independence, United States President James Monroe, first declared the Monroe doctrine on 2 December 1823.

See also

- Chilean Navy

- List of decommissioned ships of the Chilean Navy

Notes

- "The navy list in 1818 -the year that Cochrane arrived in Chile- was dominated by British names, and in 1820 the majority of the fifty officers, and 1,600 sailors in the new Chilean Navy were from Britain." A History of the British Presence in Chile. William Edmunson. 2009, Palgrave Macmillan page 74

References

- Georg von Rauch, Conflict in the Southern Cone, ISBN 0-275-96347-0, Praeger publishers, 1999, page 143

- Bartolomé Mitre, Origen de la Escuadra chilena Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 29 December 2011

- Lawrence Sondhaus, Naval warfare, 1815–1914, 2001, by Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21477-7, url

- Malcolm Deas, Anthony McFarlane, Gustavo Bell, Matthew Brown, Eduardo Posada Carbó, The role of Great Britain in the Independence of Colombia, ISBN 978-958-8244-74-7, June 2011, Bogotá, Colombia

- Diego Barros Arana, Historia general de Chile

- Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, I.B. Tauris & Co ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6

- Godoy Araneda, Lizandro, "El corso en el derecho chileno" (PDF), Revista Marina, retrieved 1 January 2013

- Renato Valenzuela Ugarte (1 January 1999). Bernardo O'Higgins: Estado de Chile y el Poder Naval en la Independencia de Los Países Del Sur de América. Andres Bello. ISBN 978-956-13-1604-1. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- "Armada de Chile | Bueras, Santiago, bergantín". Armada de Chile. April 27, 2012.

- "Armada de Chile | El Chileno, bergantín". Armada de Chile. November 18, 2010.

- "Armada de Chile | La Fortuna, lanchón". Archived from the original on 2013-01-15.

- "Armada de Chile | La Fortuna, goleta (2da)". Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- "Armada de Chile | Minerva, barca". Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- "Armada de Chile | Maipú, bergantín lanzafuego". Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- "Congreso, goleta (1º)". Armada de Chile. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- "Nuestra Señora del Carmen, goleta". Armada de Chile. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- "Rosa de los Andes, corbeta". Armada de Chile. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16.

- Given by William L. Neumann, United States Aid to the Chilean Wars of Independence, The Hispanic American Historical Review, Volume 27, 1947, pp. 204-219

- Etcheverry, Gerardo, Principales naves de guerra a vela hispanoamericanas, retrieved 11 January 2011

- There are two versions of the transference: some historians asserts that the ship was handed over to the Chileans by a Spanish captain but others say that the ship was captured in Valparaíso

- Marley, David (1998), Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the New World, 1492 to the present, ABC-CLIO Ltd, p. 422

- Lopez Urrutia, Carlos (1969), Historia de la Marina de Chile, Editorial Andrés Bello

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 28, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) retrieved 5. January 2011

- Brian Vale, "Cochrane in the Pacific: fortune and freedom in Spanish America", page 18

- Antonio García Reyes in Memoria sobre la Primera Escuadra Nacional, Imprenta del Progreso, Santiago de Chile, Octubre de 1846, page 100.

- (Cubitt, 1976: 193-195)

- (García Reyes, 1846. 10)

- Baeza 2017. page 80

- Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, I.B. Tauris & Co ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6, The author gives in pages 25 and 43 different figures of the enrolled seamen: 1,200 and 1,400

- Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, I.B. Tauris & Co ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6, p 66-8

- See English translation of the Treaty in Edmund Burke, The Annual register, or, A view of the history, politics, and literature for the Year 1819, page 138

- Simon Collier, William F. Sater, A history of Chile, 1808–1994, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-56075-6

- We use here the list of Gerardo Etcheverry Principales naves de guerra a vela hispanoamericanas. Archived April 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 21. January 2011. The Hercules, Veloz and Zaragoza are not in the list.

- Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, I.B. Tauris & Co ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6, pp 141-150

- Diego Barros Arana (2000). Historia general de Chile: Parte novena : Organización de la república 1820 a 1833 (continuacíon). Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 978-956-11-1786-0. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

Literature

- Antonio García Reyes, (1817–1855), Memoria sobre la primera Escuadra Nacional read in the Universidad de Chile on 11 October 1846 (In Spanish Language)

- El poder naval realista en el Pacífico Sur durante la guerra de independencia, by Julio M. Luqui Lagleyze, published in Bioletin del Centro Naval, N° 794 Vol 117, 1999