de Havilland Firestreak

The de Havilland Firestreak is a British first-generation, passive infrared homing (heat seeking) air-to-air missile. It was developed by de Havilland Propellers (later Hawker Siddeley) in the early 1950s and was the first such weapon to enter active service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm, equipping the English Electric Lightning, de Havilland Sea Vixen and Gloster Javelin. It was a rear-aspect, fire and forget pursuit weapon, with a field of attack of 20 degrees either side of the target.[1]

| Firestreak | |

|---|---|

| Type | air-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1957–1988 |

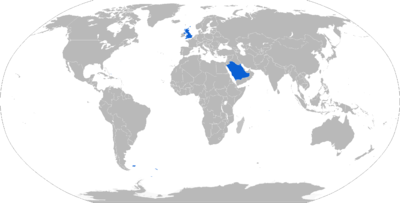

| Used by | United Kingdom, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia. |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1951 |

| Manufacturer | de Havilland Propellers |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 136 kg (300 lb) |

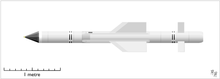

| Length | 3.19 metres (10 ft 6 in) |

| Diameter | 0.223 m (8.8 in) |

| Warhead | 22.7 kg (50 lb) annular blast fragmentation |

Detonation mechanism | proximity infrared |

| Engine | Magpie solid fuel motor |

| Wingspan | 0.75 m (30 in) |

Operational range | 4 miles (6.4 km) |

| Maximum speed | Mach 3 |

Guidance system | rear-aspect infrared |

Steering system | control surface |

Launch platform | fixed-wing aircraft |

Developed under the rainbow code "Blue Jay", Firestreak was the third heat-seeking missile to enter service, after the US AIM-4 Falcon and AIM-9 Sidewinder, both of which entered service the previous year. In comparison to those designs, the Firestreak was larger and almost twice as heavy, carrying a much larger warhead. It had otherwise similar performance in terms of speed and range.

An improved version, "Blue Vesta", was developed as part of the Operational Requirement F.155 project but ended when that project was canceled in 1957. Some portions of the Blue Vesta design were then incorporated into another concept, "Red Top". Seeking improvements over Firestreak, this entered service keeping its code name, as the Hawker Siddeley Red Top. Red Top replaced Firestreak in many roles but could not be carried on early versions of the Lightning and remained in service until 1988, when it was retired along with the last RAF Lightnings.

Development

Red Hawk

Firestreak was the result of a series of projects begun with the OR.1056 Red Hawk missile, which called for an all-aspect seeker that could attack a target from any launch position. When this proved too ambitious for the state of the art, another specification lacking the all-aspect requirement was released as Blue Sky, which briefly entered service as Fireflash the year before Firestreak.

Blue Jay

Red Hawk continued in its original form for a time before it too was rewritten as a lower-performance specification that was released in 1951 as OR.1117, and given the Ministry of Supply rainbow codename Blue Jay.[1]

Blue Jay developed as a fairly conventional-looking missile with cropped delta wings mounted just aft of the midpoint and small rectangular control surfaces in tandem towards the rear. Internally, things were considerably more complex. The size of the tube-based electroncs left little room for a warhead, which had to be moved to the rear of the fuselage. This left no room for the rear-mounted control find, which were instead operated by nose-mounted actuators via long pushrods. The actuators were powered by compressed air from bottles at the rear.

The lead telluride (PbTe) IR seeker was mounted under an eight-faceted conical arsenic trisulphide "pencil" nose and was cooled to −180 °C (−292.0 °F) by anhydrous ammonia to improve the signal to noise ratio. The unusual faceted nose was chosen when a more conventional hemispherical nose proved prone to ice accretion.[2] There were two rows of triangular windows in bands around the forward fuselage, behind which sat the optical proximity fuzes for the warhead. The warhead was at the rear of the missile, wrapped around the exhaust of the Magpie rocket.

The electronics, made from vacuum tubes, generated significant heat. For this reason, the Firestreak missile undergoing a ground test was cooled by Arcton, and in flight by ammonia pumped through the missile from the parent aircraft. The ammonia was also used to cool the seeker, which improved its signal-to-noise ratio.

Service

The first airborne launch of Blue Jay took place in 1955 from a de Havilland Venom, the target drone - a Fairey Firefly - being destroyed.[2] Blue Jay Mk.1 entered service in 1957 with the RAF, where it was named Firestreak. Firestreak was deployed by the Royal Navy and the RAF in August 1958;[3] it was the first effective British air-to-air missile.[3]

For launch, the missile seeker was slaved to the launch aircraft's radar (Ferranti AIRPASS in the Lightning and GEC AI.18 in the Sea Vixen) until lock was achieved and the weapon was launched, leaving the interceptor free to acquire another target.[4] A downside was that the missile was highly toxic (due to either the Magpie rocket motor or the ammonia coolant) and RAF armourers had to wear some form of CRBN protection to safely mount the missile onto an aircraft. "Unlike modern [1990s] missiles, ... Firestreak could only be fired outside cloud, and in winter, skies were rarely clear over the UK."[5]

Improvements

Two minor Blue Jay variants were studied but not adopted. The Blue Jay Mk.2 included the more powerful Magpie II motor and a PbTe seeker which offered better detection capabilities. Blue Jay Mk.3 had an increased wingspan and reduced performance motor. The derated motor was intended to limit acceleration when launched from supersonic rocket-powered interceptors such as the Saunders-Roe SR.177 and Avro 720, where the additional speed imparted by the Magpie II would have given it a maximum speed so high it would suffer from adverse aerodynamic heating.[6]

Looking for an improved weapon for the Operational Requirement F.155 interceptors, in 1955 the Air Ministry issued OR.1131 for an all-aspect design capability against enemy aircraft traveling at Mach 2. De Havilland responded with Blue Jay Mk.4, which was later given its own rainbow code, Blue Vesta. This adopted the PbTe seeker of Mk.2, further improved by cooling it to improve its sensitivity in what became known as the "Violet Banner" seeker. The motor was further upgraded to the new Magpie III. To handle the aerodynamic heating issues, the fins were made of steel rather than aluminum, and featured cut-away sections to keep the rear portions of the surfaces out of the Mach cones, a feature they referred to as "mach tips".[7][lower-alpha 1] Work on Mk.4 was curtailed after 1956 as the RAE decided that the rapid closing speeds of two Mach 2+ aircraft would be so quick that the missile would have no chance to be launched while still within the range of its seeker.[7]

In August 1956, the Fleet Air Arm took over development of the Blue Jay line with Blue Jay Mk.5, replacing the IR seeker with a semi-active radar homing (SARH) system intended to be used with the De Havilland Sea Vixen's AI.18 radar with a special continual wave illuminator mode. This was otherwise identical to Mk.4, differing only by replacing its seeker section with a longer ogive nose cone holding the radar receiver antenna. Problems fitting the illuminator antenna to the Sea Vixen ended work on this project. In November 1957 it was briefly restarted under the name Blue Dolphin as other radar-guided developments ended, but this was never deployed.[7]

Red Top

After the fallout of the 1957 Defence White Paper led to the cancellation of the F.155 and many other interceptor projects, the English Electric Lightning was allowed to continue largely because development was almost complete. This left it with no modern weapon, so Blue Vesta was reactivated in a slightly modified form.[3] In November 1957, paperwork with the Blue Vesta name on it was considered disclosed and the project was assigned the new name "Red Top".[8]

In contrast to the Mk.4 there were several important changes. The motor was further upgraded from the Magpie III to the new Linnet which offered significantly higher performance and boosted the typical top speed of the missile from Mach 2.4 to 3.2 whilst almost doubling effective range to 7.5 miles (12.1 km). The adoption of transistorized circuits in place of the former thermionic valves eliminated the need for cooling the electronics, as well as making the guidance section significantly smaller. This allowed the warhead to be moved from its former position near the tail to the midsection, which also allowed it to grow in size and weight, replacing the former blast-fragmentation type with an expanding-rod system that was significantly deadlier. This also allowed the steering fin actuators to be placed at the rear of the missile, eliminating the pushrods and their associated complexity.

Given the elimination of the ammonia cooling, which was also used by the Violet Banner seeker of the Mk.4, the decision was made to use a simplified seeker that did not require cooling. This led to a new indium antimonide (InSb) design that was cooled with purified air at 3,000 psi (21 MPa) filtered to 3 μm. This reduced its sensitivity compared to Violet Banner, lacking its true all-aspect ability, but further simplified the design and eliminated ground handling concerns.

Never given its own name by the RAF, the new design entered service in 1964 as Red Top. It was faster and had a longer range than Firestreak,[3] and "was capable of all aspect homing against super-sonic targets."[3] Despite Red Top being intended to replace Firestreak, Firestreak remained in limited service until the final retirement of the Lightning in 1988; Red Top's larger fins required more vertical tail to stabilize the effects of its larger wings, so Firestreak remained in use on older models of the Ligntning.

Operators

Notes

- More widely known today as a cropped delta.

References

Citations

- Gibson 2007, p. 33

- Gibson 2007, p. 34

- Boyne, Walter J, Air Warfare: an International Encyclopedia, Volume 1, pub ABC-CLIO Inc, 2002, ISBN 1-57607-345-9 p267.

- Gibson 2007, p. 35

- Black, Ian, The Last of the Lightnings, pub PSL, 1996, ISBN 1-85260-541-3, p141.

- Gibson & Buttler 2007, p. 35.

- Gibson & Buttler 2007, p. 36.

- Gibson & Buttler 2007, p. 40.

Bibliography

- Gibson, Chris; Buttler, Tony (2007). British Secret Projects: Hypersonics, Ramjets and Missiles. Midland Publishing. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-85780-258-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)