Figure skating spins

Spins are an element in figure skating in which the skater rotates, centered on a single point on the ice, while holding one or more body positions. They are performed by all disciplines of the sport, single skating, pair skating, and ice dance, and are a required element in most figure skating competitions. As The New York Times says, "While jumps look like sport, spins look more like art. While jumps provide the suspense, spins provide the scenery, but there is so much more to the scenery than most viewers have time or means to grasp".[1] According to world champion and figure skating commentator Scott Hamilton, spins are often used "as breathing points or transitions to bigger things"[1]

| Figure skating element | |

|---|---|

| Element name: | Spin |

| Scoring abbreviation: | Sp |

Figure skating spins, along with jumps, spirals, and spread eagles were originally individual compulsory figures, sometimes special figures. Unlike jumps, spins were a "graceful and appreciated"[2] part of figure skating throughout the 19th century. They advanced between World War I and World War II; by the late 1930s, all three basic spin positions were used. There are two types of spins, the forward spin and the backward spin. There are three basic spin positions: the upright spin, the sit spin, and the camel spin. Skaters also perform flying spins and combination spins. The International Skating Union (ISU), figure skating's governing body, delineates rules, regulations, and scoring points for each type and variety of spin.

Background

Figure skating spins, along with jumps, spirals, and spread eagles were originally individual compulsory figures, sometimes special figures.[3] Unlike jumps, spins were a "graceful and appreciated"[2] part of figure skating throughout the 19th century. Jean Garcin, who wrote one of the first books about figure skating in the early 1800s, recognized their beauty, especially when used as a way to conclude a figure artistically. Figure skater and historian Irving Brokaw categorized spin variations not into positions as they are categorized today, but into different changes of the skating foot. He wrote in the early 1900s about the importance of spins and insisted that advanced skaters should have been able to execute one or more spin varieties on either foot.[2] Spins were performed in the early days of pair skating by more skilled and experienced skaters, often as conclusions to their programs.[4] Figure skating historian James Hines stated that even in modern skating, spins are placed at the end of programs to make them more exciting.[2]

Spins "advanced greatly"[2] between World War I and World War II. Sonja Henie's spins, which can be viewed in her films made during the 1930s, often reached 40 or more revolutions and were "usually well-centered, fast, and as exciting to watch today as they were then".[2] By the late 1930s, all three basic spin positions were used. Skaters were expected to spin in both directions at the time, but as spins became faster and more difficult, they were only expected to spin in one direction.[2] Skaters like Ronnie Robertson in the 1950s, Denise Biellmann in the 1980s, and Lucinda Ruh in the 1990s, had "an uncanny ability to perform spins", and were sometimes able to execute up to seven revolutions per second in the upright position.[5] However, as researchers Lee Cabell and Erica Bateman stated in 2018, "Unfortunately, modern figure skaters often do not achieve these types of revolutions because the rules require skaters to perform spins in different body positions".[5]

World champion and commentator Scott Hamilton reported that Robertson would spin so fast that he would break blood vessels in his hands.[1] Hamilton also stated that Robertson and Ruh were so good at executing spins that they "would find that part of the blade that had no friction with the ice, and they would spin at the same speed forever. It just seemed like it would never end, and they could change positions and then recrank the spin and make it happen again".[1] Ruh, however, suffered from chronic nausea and dizziness, and would regularly lose consciousness during practices or in hotel rooms. She was eventually diagnosed with miniconcussions that were probably linked to executing spins and the forces generated by them, especially during layback spins. Ruh also later stated that the rotational speeds she was able to maintain and the long hours practicing and performing them most likely contributed to the severity of her injuries.[1]

Pair spins became part of competitive figure skating between the world wars;[6] side-by-side spins, along with death spirals, lifts, throw jumps, side-by-side jumps, and side-by-side footwork sequences, were a part of pair skating by the 1930s.[7] In ice dance, there were limitations to dance spins, as well as for other moves associated with pair skating like jumps and lifts, when ice dance became a competitive sport and throughout the 1950s. Spins were limited to a maximum of one-and-a-half revolutions when done by one partner and to two-and-a-half revolutions when they spun around each other. These limitations were put in place to ensure its distinction from pair skating.[8]

Execution

.jpg)

As The New York Times says, "While jumps look like sport, spins look more like art. While jumps provide the suspense, spins provide the scenery, but there is so much more to the scenery than most viewers have time or means to grasp".[1] According to Scott Hamilton, spins are often used "as breathing points or transitions to bigger things"[1] and are more difficult to explain to the audience "because there is so much going on".[1] Hamilton stated that explaining the intricacies of spins, like edge changes, is challenging because they are difficult to see.[1]

Most beginning skaters learn how to execute spins in the counter-clockwise direction, but if a skater is left-handed, he or she should execute them clockwise.[9] Most spins are executed on one foot, except for the two-foot spin, which beginning skaters tend to learn first, and the cross-foot spin.[10][11][12] The two-foot spin consists of three essential parts—the setup, the windup, and the spin—as well as the exit, which can be done by rotating in a closed spinning position until stopping or by using a back inside edge with a change of foot.[13]

The effect of linear and rotational forces is most apparent and most powerful when performing spins. The successful accomplishment of spins depends upon the effective management of angular momentum, which occurs during the entrance of a spin and ends once a skater is in the spin and all linear force is translated into angular velocity. The skater rotates around the point at which the blade touches the ice, the most important point in the vertical axis made by the skater's body, and a fixed vertical axis that extends from the blade on the ice to the highest point in his or her body. The absence of angular momentum means that fewer variables, or vectors, influence the resulting motion, so if the center of gravity is maintained, spins should be easier to perform than other elements such as jumps.[14] The change from angular momentum to angular speed around a fixed vertical axis is difficult to control, though, as is the change from one force into another in general. Moving forward quickly also cannot be efficiently converted into fast angular speed, so the conversion of fast linear motion, which produces a lot of force, into fast rotational motion is small. Therefore, is it a waste of energy to build up speed going into a spin; entering a spin slowly achieves the same result and will probably be more consistent.[9]

A spin consists of the following parts: preparation, entry, spin, and exit. During the preparation phase, skaters decrease the radius of the skating curve and velocity/speed, which means that the skater must increase how much he or she leans into the spin. As researchers Lee Cabell and Erica Bateman state, "A step against the gliding edge exerts a force on the ice; the resultant torque about the axis of rotation results in the angular momentum that is used during the spin".[5] Greater force during the initial push of the spin's preparation phase results in greater torque and angular momentum, which will result in a faster spin.[5] The International Skating Union defines a spin exit as "the last phase of the spin and includes the phase immediately following the spin".[15] The exit coming out of a spin occurs in two stages: breaking the spin's rotational spin and the exit itself. There are many exit variations of spins.[16] A difficult exit is any jump or movement a skater performs that makes the exit significantly more difficult.[17]

The entry phase produces a logarithmic curve with an indefinite number of radii. smallest at the end and largest at the beginning. When the entry curve radius is decreased, the skater will change the angle of his or her lean towards the vertical axis, gradually reducing the velocity/speed. The curve ends with a 3 turn, then the center of gravity is slightly lower, resulting in the skater beginning to spin. After the initiation of the actual spin, he or she will exhibit a large moment of inertia. His or her shoulders are square to the hips and rotating with each other at the same angular velocity. The body's center of gravity must be directly above the base of support (for example, where the blade is in contact with the ice) in order for the skater to execute a balanced spin. If the spin is not balanced and centered, the vertical projection of the center of gravity moves away from the base of support, which results in the spinning blade making small loops on the ice.[18]

The goal of most spins is to rotate as quickly as possible, to have a well-defined and pleasing body position, to maintain perfect balance before, during, and after the spin, and to remain in one place, called centering, while executing a spin.[19] A good spin should rotate in one place on the ice, "drawing a series of tiny overlapping circles on top of each other" into the ice.[20] A spin that is not centered will travel across the ice, "producing a series of loops strung out along a curve or straight line, so that the skater will end the spin several feet away from the spot on the ice where she began it".[21] In order to rotate rapidly, the skater must increase his or her speed (rotations per minute), which is accomplished by reducing the distance of the vertical axis from the parts of his or her body. This is done by bringing the arms and free leg closer to the body, in line with the vertical axis. Since the true center of gravity is at the point in which the blade meets the ice, the skater must also lower his or her arms and free leg toward that point. The force created by the spin is generated outward and upward, or via the path of least resistance, as the speed increases. When skaters allow the force to follow the path of least resistance, however, they will lose some of the force that contributes to rotational speed, so when they increase a spin's speed, they must move their arms and free leg inward and downward. Exactly how this is done varies depending on the type of spin skaters perform.[22]

Skaters experience dizziness during spins because as they spin, their eyes focus on an immobile object and follows it until the object passes beyond their peripheral vision. Then their eyes race ahead to focus on a new object and as the spin ends, their eyes continue to follow this pattern, causing dizziness. It takes practice to train the eyes to return back to normal, which dissipates the experience of dizziness.[23]

Types/positions of spins

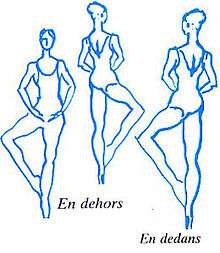

There are two types of spins, the forward spin and the backward spin. The forward spin is executed on the back inside edge of the skate and is entered into by the forward outside edge and 3 turn; the equivalent movement is ballet in the pirouette en dedans. The backward spin, which is executed on the back outside edge, is entered into by the forward inside edge and 3 turn; the equivalent movement in ballet is the pirouette en dehors.[24]

There are three basic spin positions: the upright spin, the sit spin, and the camel spin.[21][25][note 1]

Upright spin

The International Skating Union (ISU), the governing body of figure skating, defines an upright spin as a spin with "any position with the skating leg extended or slightly bent which is not a camel position".[27] British figure skater Cecilia Colledge was "responsible for the invention"[28] and the first to execute it.[29] Colledge's coach, Jacques Gerschwiler, who was a former gymnastics teacher and according to Colledge "very progressive in his ideas",[28] got the idea for the upright spin while watching one of Colledge's trainers, a former circus performer turned acrobatics instructor, train Colledge to perform backbends "by means of a rope tied around her waist".[28] The upright spin has long been associated with women's skating, but men have also performed it. Skaters include it in their programs because it increases its technical content and fulfills choreographic needs.[30]

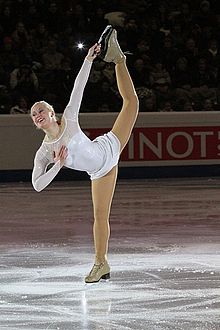

A variation of the upright spin is the layback spin, executed by holding the free leg in a back attitude position and arching the head and upper body backward so that the skater faces up towards the sky, ceiling, or further.[31] The free leg position is optional.[27] A variation of the layback spin is the Biellmann spin, made popular by world champion Denise Biellmann, which is executed by the skater grabbing the free blade and pulling the foot straight up above the head so that his or her legs are in an approximate full split with the head and back arched upward.[31] The spin "requires much strength and extreme flexibility".[32]

Figure skating champion and writer John Misha Petkovich categorizes the upright spin into two further groups, the back upright spin and the forward upright spin.[33] He calls the back upright spin "perhaps the most important spin in skating"[34] because the position skaters execute toward the end of the spin is also executed in the middle of multi-rotational jumps. Petkovich also states that the forward upright spin "may well be the most exciting basic spin in skating".[34] Skaters can attain "unbelievable" speed while performing the upright spin;[34] because of its speed, it is often the final spin in a program.[35] A variation of the upright spin is the scratchspin, so named because the skater's weight is centered between the center of the spinning blade and the first tooth of the skate's toepick, which scratches loops or circles on the ice parallel to the tracings made by the blade. When performed extremely quickly, it is also called the blur spin.[21] Another variation of the upright spin, is the sideways leaning spin, in which the skater's head and shoulders are leaning sideways and his or her upper body is arched. The free leg, as it is for the layback spin, is optional.[36]

The angular velocity of an upright spin is low, about one revolution per second, but its moment of inertia is large during its balancing stage. As the angular velocity increases (up to five revolutions per second), the moment of inertia is decreased as the arms and free leg move towards the center of the spin. At this point, the center of gravity reaches its maximum as the skater stretches vertically, the moment of inertia is at its minimum, and the angular velocity is at its maximum. The skater ends the spin by opening his or her arms, which increases the moment of inertia, and he or she exits the spin on a curve.[5]

Sit spin

The sit spin, invented by figure skater Jackson Haines, "represents one of the most important spins in skating".[37] It is executed in a sitting position, with the knee of the skating leg bent and the free leg held in front.[21] It is difficult to learn, requires a great deal of energy, and is not as exciting to perform as other elements, such as jumps, but it has variations that make it more creative and pleasurable to watch.[37][38] When executing the sit spin, a skater's back should be straight and not curved, his or her hips should be lower than the skating knee, and his or her free leg should be straight.[21] The best sit spin position minimizes the moment of inertia and keeps the heaviest parts of the body as close to the vertical center of gravity as possible. This position is difficult to maintain, however, so skaters will often collapse into a low sit spin position.[39]

Camel spin

Colledge was also responsible for the invention of the sit spin; she was the first to perform it, in the mid-1930s.[2][28][29] The camel spin, also called "the parallel spin",[21] was borrowed directly from the ballet pose the arabesque, but adapted to the ice.[40] Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum speculated that the camel and layback spins, which "heightened the visual function of the skater creating interesting shapes with her body",[28] were, for the first ten years after their inventions, performed mostly by women and not by men because it was easier for women to achieve the interesting shapes they create than it is for men.[41] American skater Dick Button, however, performed the first forward camel spin, a variation of the camel spin, and made it a regular part of the repertoire performed by male skaters.[42]

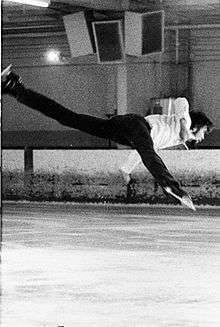

The most important difference between the sit spin and the camel spin is that the skater enters the sit spin directly instead of first developing a slow part at the beginning of the entry.[39] The camel spin is executed with the torso and the free leg stretched in opposite directions, parallel to the ice at hip level in a position similar to the arabesque position. When executed well, the stretch of the body should create a slight arch or straight line. Camel spins tend to rotate more slowly than other spins because the circumference of the camel spin's rotation is much greater than in other spin positions, so a prolonged and fast camel spin requires a great deal of technique and skill.[21] The preparation and entry phases of the camel spin are similar to the upright spin's preparation and entry phases. At the end of the entry, the skater begins to spin by executing small circles on the backward inside edge of the skate while his or her shoulders and hips rotate at the same angular velocity. His or her skating knee extends and the body rises in a locked position. Then the body stretches upward toward the head and neck while the skating leg, which is locked and straight, pushes forward.[2][25]

Other spins

A flying spin is the combination of a jump and a spin. They can be appealing for the audience to watch and exciting for the skater to perform.[43] Petrovich describes three types of flying spins: the flying camel, the flying sit spin, and the butterfly. The flying camel consists of a jump from a left forward outside edge, about one revolution in the air, with the landing executed in a camel spin. Button might have been the first skater to successfully execute the flying camel; for many years, it was called the "Button camel".[42][44] The flying sit spin was first performed by Buddy Vaughn and Bill Grimditch, who were students of figure skating coach Gustav Lussi, but Button and Ronnie Robertson made it famous. It consists of a take-off from a left forward outside edge, a sit spin position in the air during one-and-a-half revolutions, and a landing in a sit spin.[45] According to Petkevich, "When the jump is high, it can be an exhilarating maneuver for skater and audience alike".[45] The butterfly spin is so named because it describes the position in the air. It consists of a take-off from both feet, a body position horizontal to the ice, and a landing in a back spin. It is often performed at the end of a skater's program because although it adds to a program's technical content, it does not require much precision or energy to execute.[46]

The jump section of flying spins is executed at the beginning of the spin and is part of the entrance into it. The angular momentum on the entrance, like for all spins, must be converted into pure rotational momentum. In ordinary jumps, angular momentum allows the skater to travel a long distance across the rink and propel high into the air, but for flying spins, the principles that govern the spin dominate the jump portion of the spin. The goal is to minimize forward motion on the jump portion. Creating speed on the spin portion is also a goal, but a flying spin never achieves the speed of a basic spin because some of the forces assigned to achieving the speed in a basic spin must be used to achieve height on the flying spin's jump portion. Centering the spin after the jump depends on converting all the angular momentum into rotational momentum. Mastering the flying spin takes less time and practice if skaters have already mastered basic spin techniques and good jumping ability.[43]

Combination spins are required in the programs of all disciplines.[47] Flying spins and basic spins can be combined in any number of variations. The maintenance, or acceleration, of the rotational momentum created on the entrance of the first spin is the most important principle governing the execution of combination spins, which require quick movements during the spins' transitions. When a change of feet is required to successfully perform combination spins, the center of rotation of subsequent spins should be as close as possible to the center of rotation of the first spin of the combination.[48] Combination spins must include more than one position and may or may not involve a change of foot.[31]

Photo gallery of upright spins

Scratch spin

Guan Jinlin

Carolina Kostner, 2009

Sasha Cohen, 2003

Alissa Czisny, 2005

Shawn Sawyer, 2008

Maé-Bérénice Méité, 2018

Nikolaj Majorov, 2020

Maria Sotskova, 2018

Photo gallery of camel spins

Camel spin

Emily Hughes, 2007

Shizuka Arakawa, 2003

Butterfly jump

Ben Ferreira, 2004

Yuna Kim, 2008 .jpg)

Evan Lysacek, 2006

Rules and regulations

Single skating

Spins must have the following characteristics to earn the most points: they must have good speed and/or acceleration; they must be executed effortlessly; and they must have good control and clear position(s), even for flying spins, which must have a good amount of height and air/landing position. Also important but not required are the following characteristics: the spin must maintain a center; the spin must be original and creative; and the element must match the music.[49]

If a skater performs a spin that has no basic position with only two revolutions, or with less than two revolutions, he or she does not fulfill the position requirement for the spin, and receives no points for it. A spin with less than three revolutions is not considered a spin; rather, it is considered a skating movement.[50] The flying spin and any spin that only has one position must have six revolutions; spin combinations must have 10 revolutions. Required revolutions are counted from when the skater enters the spin until he or she exits out of it, except for flying spins and the spins in which the final wind-up is in one position.[51] Skaters increase the difficulty of camel spins by grabbing their leg or blade while performing the spin.[52]

A skater earns points for a spin change of edge only if he or she completes the spin in a basic position. Fluctuations in speed and variations in the positions of a skater's arms, head, and free leg are permitted. A skater must execute at least three revolutions before and after a change of foot. If a skater tries to perform a spin and his or her change of foot is too far apart (thus creating two spins instead of one), only the part executed before the change of foot is included in the skater's score.[50] The change of foot is optional for spin combinations and for single-position spins.[51] If he or she falls while entering a spin, the skater can fill the time lost by executing a spin or spinning movement; however, this movement will not be counted as an element. Difficult spin variations increase the level of a spin and are worth more points. These variations include a movement of the body part, head, leg, arm, or hand that requires flexibility or physical strength and that effects the balance of the skater's main body core. There are 11 categories of difficult spin variations; three are in the camel spin position, based on the direction of the skater's shoulder line.[17]

A spin combination must have at least "two different basic positions with 2 revolutions in each of these positions anywhere within the spin".[50] Skaters earn the full value of a spin combination when they include all three basic positions. The number of revolutions in non-basic positions are included in the total number of revolutions, but changing to a non-basic position is not considered a change of position. The change of foot and change of position can be made at the same time or separately, and can be performed as a jump or as a step-over movement. Non-basic positions are allowed during spins executed in one position or, for single skaters, during a flying spin.[50] Difficult exits must have a significant impact on the spin's execution, control, and balance.[17]

Pair skating

Solo spin combinations

The solo spin combination must be performed once during the short program of pair skating competitions, with at least two revolutions in two basic positions. Both partners must include all three basic positions in order to earn the full points possible. There must be a minimum of five revolutions made on each foot.[53] Spins can be commenced with jumps and must have at least two different basic positions, and both partners must include two revolutions in each position. A solo spin combination must have all three basic positions (the camel spin, the sit spin, and upright positions) performed by both partners, at any time during the spin to receive the full value of points, and must have all three basic positions performed by both partners to receive full value for the element. A spin with less than three revolutions is not counted as a spin; rather, it is considered a skating movement. If a skater changes to a non-basic position,[note 2] it is not considered a change of position. The number of revolutions in non-basic positions, which may be considered difficult variations, are counted towards the team's total number of revolutions. Only positions, whether basic or non-basic, must be performed by the partners at the same time.[55][54]

If a skater falls while entering into the spin, he or she can perform another spin or spinning movement immediately after the fall, to fill the time lost from the fall, but it is not counted as a solo spin combination. A change of foot, in the form of a jump or step over, is allowed, and the change of position and change of foot can be performed separately or at the same time.[53] Pair teams require "significant strength, skill and control"[54] to perform a change from a basic position to a different basic position without performing a nonbasic position first. They also have to execute a continuous movement throughout the change, without jumps to execute it, and they must hold the basic position for two revolutions both before and after the change.[54] They lose points if they take a long time to reach the necessary basic position.[56]

Pair teams earn more points for performing difficult entrances into their spins.[note 3] Difficult flying entrances count, although backward entry into the spin and a flying camel do not. All entrances must have a "significant impact"[57] on the spin's execution, balance, and control, and the intended spin position must be achieved within the team's first two revolutions. The rules surrounding difficult variations, which also apply to single skaters and to both partners, are also worth more points.[note 4] There are 11 categories of difficult solo spin variations.[note 5]

Spin combinations

Both junior and senior pair teams must perform one pair spin combination, which may begin with a fly spin, during their free skating programs.[58] Pair spin combinations must have at least eight revolutions, which must be counted from "the entry of the spin until its exit".[59] If spins are done with less than two revolutions, pairs receive zero points; if they have less than three revolutions, they are considered a skating movement, not a spin. Pair teams cannot, except for a short step when changing directions, stop while performing a rotation.[59][58] Spins must have at least two different basic positions, with two revolutions in each position performed by both partners anywhere within the spin; full value for pair spin combinations are awarded only when both partners perform all three basic positions.[55] A spin executed in both clockwise and counter-clockwise directions is considered one spin. When a team simultaneously performs spins in both directions that immediately follow each other, they earn more points, but they must execute a minimum of three revolutions in each direction without any changes in position.[60]

Both partners must execute at least one change of position and one change of foot (although not necessarily done simultaneously); if not, the element will have no value.[61] Like the solo spin combination, the spin combination has three basic positions: the camel spin, the sit spin, and the upright spin. Also like the solo spin combination, changes to a non-basic position is counted towards the team's total number of revolutions and are not considered a change of position. A change of foot must have at least three revolutions, before and after the change, and can be any basic or non-basic position, in order for the element to be counted.[62]

Fluctuations of speed and variations of positions of the head, arms, or free leg are allowed.[53] Difficult variations of a combined pair spin must have at least two revolutions. They receive more points if the spin contains three difficult variations, two of which can be non-basic positions, although each partner must have at least one difficult variation. The same rules apply for difficult entrances into pair spin combinations as they do for solo spin combinations, except that they must be executed by both partners for the element to count towards their final score.[60] A difficult exit, in which the skaters exit the spin in a lift or spinning movement, is defined as "an innovative move that makes the exit significantly more difficult".[60] If one or both partners fall while entering a spin, they can execute a spin or a spinning movement to fill up time lost during the fall.[58]

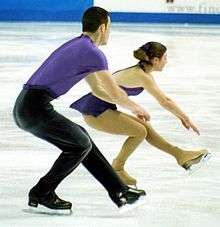

Photo gallery of pair spins

Aliona Savchenko and Robin Szolkowy, 2008

Pair sit spin

Dan Zhang and Hao Zhang, 2007

Tatiana Totmianina and Maxim Marinin, 2005

Side by side spins

Tiffany Vise and Derek Trent, 2006

Side by side sit spins

Johanna Purdy and Kevin Maguire, 2002

Pair sit and catch-foot layback

Lubov Iliushechkina and Nodari Maisuradze, 2008

Dance spins

There are two types of dance spins: the spin and the combination spin.[63] The ISU defines a dance spin as "a spin skated by the Couple together in any hold".[64] The ISU also states, "It should be performed on the spot around a common axis on one foot by each partner simultaneously".[64] The combination spin is defined as "a spin performed as above after which one change of foot is made by both partners simultaneously and further rotations occur".[65] The solo spin, or pirouette, is allowed and defined as "a spinning movement performed on one foot",[64] with or without the partner's assistance, performed by both partners at the same time but around separate centers. The ISU announces dance spin variations or combinations at the beginning of each season.[66]

Dance spins have three positions. The upright position is done on one foot with the skating leg slightly bent or straight and with the upper body upright, bent to the side, or with an arched back. The sit position is done on one foot, with "the skating leg bent in a one-legged crouch position and with the free leg forward, either to the back or the side".[65] The camel position is done on one foot, with "the skating leg straight or slightly bent forward, and with the free leg extended or bent forward horizontally or higher".[65][note 6]

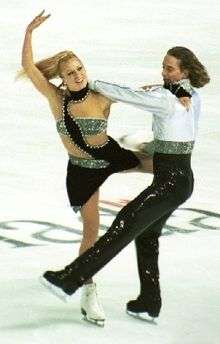

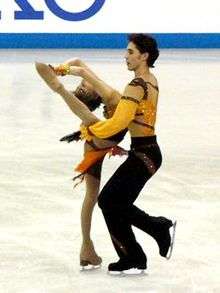

Photo gallery of dance spins

Shae-Lynn Bourne and Viktor Kraatz, 2007

Sit spin position and layback position

Lubov Iliushechkina and Nodari Maisuradze, 2008

Isabelle Delobel and Olivier Schoenfelder, 2007  Nathalie Pechalat and Fabian Bourzat, 2006

Nathalie Pechalat and Fabian Bourzat, 2006 Jana Khokhlova and Sergei Novitski, 2003

Jana Khokhlova and Sergei Novitski, 2003 Aliona Savchenko and Robin Szolkowy, 2008

Aliona Savchenko and Robin Szolkowy, 2008 Tanith Belbin and Benjamin Agosto, 2008

Tanith Belbin and Benjamin Agosto, 2008

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Figure skating spins. |

Footnotes

- See ISU's "Communication No. 2168" for points awarded for each spin and varieties of spin.[26]

- A non-basic position is defined as "all the other positions not fulfilling the requirements of any basic positions".[54]

- An "entrance into a spin" is defined as "the preparation immediately preceding a spin" and can include the spin's beginning phase.[57]

- "Difficult variations" are defined as "a movement of a body part, leg, arm, hand or head, which requires more physical strength or flexibility and has an effect on the balance of the main body core".[57]

- See the 2019/2020 Technical Panel Handbook.[56]

- Also see the "2019—2020 U.S. Figure Skating Rulebook".[67]

References

- Clarey, Christopher (19 February 2014). "Appreciating Skating's Spins, the Art Behind the Sport". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Hines, p. 103

- Hines, p. 100

- Hines, p. 82

- Cabell and Bateman, p. 23

- Hines, p. 5

- Hines, p. 126

- Hines, p. 173

- Petkevich, p. 128

- Kestnbaum, p. 279

- Petkevich, p. 136

- Petkevich, p. 143

- Petkovich, p. 26

- Petkevich, p. 127

- "Communication No. 2334: Single and Pair Skating". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 8 July 2020. p. 3. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Petkevich, pp. 129–130

- "Communication No. 2334". International Skating Union. 8 July 2020. p. 3. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Cabell and Bateman, p. 24

- Petkevich, p. 135

- Kestbaum, pp. 279–280

- Kestnbaum, p. 280

- Petkevich, pp. 127–128

- Petkevich, pp. 128–129

- Petkevich, p. 129

- Cabell and Bateman, p. 25

- "Communication No. 2168: Single & Pair Skating". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 23 May 2018. pp. 3–5, 7–8. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 102

- Kestnbaum, p. 107

- Hines, p. 112

- Petkevich, p. 154

- Kestnbaum, p. 281

- Hines, p. 227

- Petkevich, pp. 139–140

- Petkevich, p. 140

- Petkovich, p. 141

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 102–103

- Petkevich, p. 144

- Petkevich, p. 148

- Cabell and Bateman, p. 26

- Petkevich, p. 150

- Kestnbaum, pp. 107–108

- Kestnbaum, p. 93

- Petkevich, p. 157

- Petkevich, p. 158

- Petkevich, p. 163

- Petkevich, p. 174

- S&P/ID 2018, pp. 105, 113, 128

- Petkevich, p. 177

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 13

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 103

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 110

- Hill, Maura Sullivan (6 February 2018). "All the Figure Skating Lingo You Need to Know Before the Olympics". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Tech Panel, p. 7

- Tech Panel, p. 8

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 113

- Tech Panel, p. 10

- Tech Panel, p. 9

- Tech Panel, p. 12

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 119

- Tech Panel, p. 14

- S&P/ID 2018, pp. 113, 119

- Tech Panel, p. 13

- S&P/ID, pp. 127-128

- S&P/ID, p. 127

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 128

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 130

- "The 2020 Official U.S. Figure Skating Rulebook" (PDF). Colorado Springs, Colorado: U.S. Figure Skating. July 2019. p. 248. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

Works cited

- Cabell, Lee and Erica Bateman (2018). "Biomechanics in figure skating". In Jason D. Vescovi and Jaci L. VanHeest (Eds.) The Science of Figure Skating, pp. 13–34. New York: Routledge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0

- Hines, James R. (2006) Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07286-4.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- Petkevich, John Misha (1988). Sports Illustrated Figure Skating: Championship Techniques (1st ed.). New York: Sports Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-4616-6440-6. OCLC 815289537.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2018". (S&P/ID 2018) International Skating Union. 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Technical Panel Handbook: Pair Skating 2019/2020" (PDF). (Tech Panel) ISU Judging System. International Skating Union. 23 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.