Eyjafjallajökull

Eyjafjallajökull (Icelandic: [ˈeiːjaˌfjatl̥aˌjœːkʏtl̥] (![]()

| Eyjafjallajökull | |

|---|---|

| Guðnasteinn Hámundur | |

Gígjökull, Eyjafjallajökull's largest outlet glacier covered in volcanic ash | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | Mountain: 1,651 m (5,417 ft) Glacier: 1,666 m (5,466 ft) [1] |

| Coordinates | 63°37′12″N 19°36′48″W [2] |

| Geography | |

Eyjafjallajökull Iceland | |

| Location | Suðurland, Iceland |

| Parent range | N/A |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | East Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | March to June 2010 |

Geography

Eyjafjallajökull consists of a volcano completely covered by an ice cap. The ice cap covers an area of about 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), feeding many outlet glaciers. The main outlet glaciers are to the north: Gígjökull, flowing into Lónið, and Steinholtsjökull, flowing into Steinholtslón.[6] In 1967, there was a massive landslide on the Steinholtsjökull glacial tongue. On 16 January 1967 at 13:47:55 there was an explosion on the glacier. It can be timed because the seismometers at Kirkjubæjarklaustur monitored the movement. When about 15,000,000 cubic metres (530,000,000 cubic feet) of material hit the glacier a massive amount of air, ice, and water began to move out from under the glacier into the lagoon at the foot of the glacier.[6]

The mountain itself, a stratovolcano, stands 1,651 metres (5,417 ft) at its highest point, and has a crater 3–4 kilometres (1.9–2.5 mi) in diameter, open to the north. The crater rim has three main peaks (clockwise from the north-east): Guðnasteinn, 1,500 metres (4,900 ft); Hámundur, 1,651 metres (5,417 ft); and Guðnasteinn, 1,497 metres (4,911 ft). The south face of the mountain was once part of Iceland's coastline, from which, over thousands of years, the sea has retreated some 5 kilometres (3 mi). The former coastline now consists of sheer cliffs with many waterfalls, of which the best known is Skógafoss. In strong winds, the water of the smaller falls can even be blown up the mountain. The area between the mountain and the present coast is a relatively flat strand, 2 to 5 km (1 to 3 miles) wide, called Eyjafjöll.

The Eyjafjallajökull volcano last erupted on 14 April 2010 in Iceland. It left behind vast ash clouds so large that in some areas daylight was entirely obscured. The cloud not only darkened the sky but also interfered with hundreds of plane flights. However, the people of Iceland were not concerned about the ash clouds: they were more concerned about flooding. That year all the residents close to the volcano had to evacuate in case the area flooded. When the volcano erupted, all the melted ice had to go somewhere. It did not flood that much: most of it went into rivers, but if it had flooded down the farm valleys it could have swept away all the farms in the valley. The farms in the valley were however covered in a soft layer of ash, which the farmers thought would give bad crops, but the warmth and nutrition from the ash enabled the crops to grow rather well.

Etymology

The name means "glacier" (or more properly here "ice cap") of the Eyjafjöll. The word jökull, meaning glacier or ice cap, is a cognate with the Middle English word ikel surviving in the -icle of English icicle.

Eyjafjöll is the name given to the southern side of the volcanic massif together with the small mountains which form the foot of the volcano.

The name Eyjafjöll is made up of the words eyja (genitive plural of ey, meaning eyot or island), and the plural word fjöll, meaning fells or mountains, and together literally means: "the mountains of the islands". The name probably refers to the close by archipelago of Vestmannaeyjar.

The word fjalla is the genitive plural of fjöll, and so Eyjafjalla is the genitive form of Eyjafjöll and means: "of the Eyjafjöll". A literal part-by-part translation of Eyjafjallajökull would thus be "Islands' Mountains' ice cap".

Eyjafjallajökull is sometimes referred to by the numeronym "E15".[7]

Geology

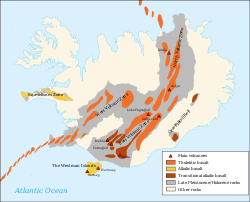

The stratovolcano, whose vents follow an east–west trend, is composed of basalt to andesite lavas. Most of its historical eruptions have been explosive.[8] However, fissure vents occur on both (mainly the west) sides of the volcano.[8]

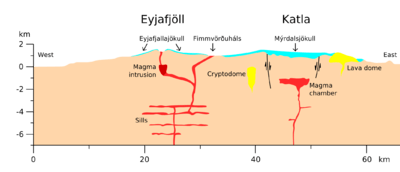

The volcano is fed by a magma chamber under the mountain, which in turn derives from the tectonic divergence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It is part of a chain of volcanoes stretching across Iceland. Its nearest active neighbours are Katla, to the northeast, and Eldfell, on Heimaey, to the southwest. The volcano is thought to be related to Katla geologically, in that eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull have generally been followed by eruptions of Katla.

Eyjafjallajökull erupted in the years 920, 1612 and 2010.

1821 to 1823 eruptions

Some damage was caused by a minor eruption in 1821.[9] Notably, the ash released from the eruption contained a large fraction of fluoride, which in high doses may harm the bone structure of cattle, horses, sheep and humans. The eruption also caused some small and medium glacier runs and flooding in nearby rivers Markarfljót and Holtsá. The eruptive phase started on 19 and 20 December 1821 by a series of explosive eruptions and continued over the next several days. The sources describe heavy ash fall in the area around the volcano, especially to the south and west.[9]

After that event the sequence of eruptions continued on a more subdued level until June 1822.

From the end of June until the beginning of August 1822, another sequence of explosive eruptions followed. The eruption columns were shot to considerable heights, with ashfall in both the far north of the country, in Eyjafjörður, and in the southwest, on the peninsula of Seltjarnarnes near Reykjavík.

The period from August to December 1822 seemed quieter, but farmers attributed the death of cattle and sheep in the Eyjafjörður area to poisoning from this eruption, which modern analysis identifies as fluoride poisoning. Some small glacier runs occurred in the river Holtsá. A bigger one flooded the plains near the river Markarfljót. (The sources do not indicate the exact date.).[10]

In 1823, some men went hiking up on Eyjafjallajökull to inspect the craters. They discovered a fissure vent near the summit caldera a bit to the west of Guðnasteinn.

In early 1823, the nearby volcano Katla under the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap erupted and at the same time steam columns were seen on the summit of Eyjafjallajökull.

The ash of Eyjafjallajökull's 1821 eruptions is to be found all over the south of Iceland. It is dark grey in colour, small-grained and intermediate rock containing about 28–40% silicon dioxide.

2010 eruptions

On 26 February 2010, unusual seismic activity along with rapid expansion of the Earth's crust was registered by the Meteorological Institute of Iceland.[11] This gave geophysicists evidence that magma was pouring from underneath the crust into the magma chamber of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano and that pressure stemming from the process caused the huge crustal displacement at Þorvaldseyri farm.[12] In March 2010, almost three thousand small earthquakes were detected near the volcano, all having a depth of 7–10 kilometres (4.3–6.2 mi).[13] The seismic activity continued to increase and from 3–5 March, close to 3,000 earthquakes were measured at the epicenter of the volcano.

The eruption is thought to have begun on 20 March 2010, about 8 kilometres (5 mi) east of the top crater of the volcano, on Fimmvörðuháls, the high neck between Eyjafjallajökull and the neighbouring icecap, Mýrdalsjökull. This first eruption, in the form of a fissure vent, did not occur under the glacier and was smaller in scale than had been expected by some geologists. The fissure opened on the north side of Fimmvörðuháls, directly across the popular hiking trail between Skógar, south of the pass, and Þórsmörk, immediately to the north.

On 14 April 2010 Eyjafjallajökull resumed erupting after a brief pause, this time from the top crater in the centre of the glacier, causing jökulhlaup (meltwater floods) to rush down the nearby rivers, and requiring 800 people to be evacuated.[5] This eruption was explosive, due to meltwater getting into the volcanic vent. It was estimated to be ten to twenty times larger than the previous one in Fimmvörðuháls. This second eruption threw volcanic ash several kilometres up in the atmosphere, which led to air travel disruption in northwest Europe for six days from 15 to 21 April 2010 and again, in May 2010, including the closure of airspace over many parts of Europe.[14] The eruptions also created electrical storms.[15] On 23 May 2010, the London Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre declared the eruption to have stopped, but stated that they were continuing to monitor the volcano.[16] The volcano continued to have several earthquakes daily, with volcanologists watching the volcano closely.[17] As of August 2010, Eyjafjallajökull was considered dormant.[18] Infrasound sensors have been installed around Eyjafjallajökull to monitor for future eruptions.[19]

Relationship to Katla

Eyjafjallajökull lies 25 km (16 mi) west of another subglacial volcano, Katla, under the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap, which is much more active and known for its powerful subglacial eruptions and its large magma chamber.[20] Each of the eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull in 920, 1612, and 1821–1823 has preceded an eruption of Katla.[21] Katla did not display any unusual activity (such as expansion of the crust or seismic activity) during the 2010 eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull, though geologists have been concerned about the general instability of Katla since 1999. Some geophysicists in Iceland believe that the Eyjafjallajökull eruption may trigger an eruption of Katla, which would cause major flooding due to melting of glacial ice and send up massive plumes of ash.[21][22] On 20 April 2010, Icelandic President Ólafur Grímsson said "the time for Katla to erupt is coming close...we [Iceland] have prepared...it is high time for European governments and airline authorities all over the world to start planning for the eventual Katla eruption".[23]

Volcanologists continue to monitor Katla, aware that any eruption from Katla following an eruption from Eyjafjallajökull has historically occurred within months of an Eyjafjallajökull eruption. The Icelandic Meteorological Office updates its website with reports of quakes at both Eyjafjallajökull and Katla.[17] On 8 July 2011 there was a jökulhlaup that destroyed a bridge on the Ring Road and caused cracks to appear on Katla's glacier.[24]

Postage stamp issue

Icelandic Post issued three special stamps in 2010 for the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano. All stamps contain real volcanic ash which fell on 17 April 2010.[25]

Popular Culture

The Volcano was featured in the 2013 movie, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, where Walter had to flee from an eruption after pursuing photographer Sean O' Connell to Iceland

See also

- List of glaciers of Iceland

- List of waterfalls of Iceland

- Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson, who photographed the 2010 eruption

- Volcanology of Iceland

References

- Bartnicki; Haakenstad; Hov (31 October 2010). "Volcano Version of the SNAP Model" (PDF). Norwegian Meteorological Institute. p. 6.

- "Eyjafjallajökull". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Eyjafjallajokull | glacier, Iceland | Britannica.com". Global.britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Thordarson, T.; Larsen, G. (2007). "Increasing signs of activity at Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland: Eruptions". Journal of Geodynamics. 43: 118–152. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..118T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.7455. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.005. Archived from the original on 2010-04-19. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Iceland's volcanic ash halts flights in northern Europe". BBC News. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "Eyjafjallajokull – Iceland on the Web". Iceland.vefur.is. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Schleicher, N.; Kramar, U.; Dietze, V.; Kaminski, U.; Norra, S. (2012). "Geochemical characterization of single atmospheric particles from the Eyjafjallajökull volcano eruption event collected at ground-based sampling sites in Germany". Atmospheric Environment. 48: 113. Bibcode:2012AtmEn..48..113S. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.05.034.

- "Eyjafjallajökull". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- Larsen, G. (1999). Gosið í Eyjafjallajökli 1821–1823 [The eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in 1821–1823] (PDF) (in Icelandic). Reykjavík: Science Institute. p. 13. Research Report RH-28-99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-22.

- ""Last Eyjafjallajökull Eruption Lasted Two Years", Iceland Review". Icelandreview.com. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- "Fasteignaskrá measurement tools". Skra.is. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Morgublaðið (26.02.2010) "Innskot undir Eyjafjallajökli". Morgunblaðið.

- Veðurstofa Íslands (5 March 2010) "Jarðskjálftahrina undir Eyjafjallajökli". Veðurstofa Ísland (The Meteorological Institute of Iceland).

- "Ash chaos: Row grows over airspace shutdown costs". BBC News. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "'Dirty thunderstorm': Lightning in a volcano".

- "Met Office: Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres". Metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Iceland Meteorological office – Earthquakes Mýrdalsjökull, Iceland". En.vedur.is. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Iceland volcano 'pauses'". Metoffice.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- Hall, Shannon (15 November 2018). "World's first automated volcano forecast predicts Mount Etna's eruptions". Nature. 563 (7732): 456–457. Bibcode:2018Natur.563..456H. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07420-y. PMID 30459379.

Working with the Icelandic Meteorological Office in Reykjavik, the scientists have installed five sensor arrays across the island to monitor infrasound waves from multiple volcanoes. Among them is the infamous Eyjafjallajökull, whose last eruption, in 2010, shut down air traffic across northwestern Europe for weeks.

- "Green.view: Back into the clouds". The Economist. 2010-04-16. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- Roger Boyes (21 March 2010). "Iceland prepares for second, more devastating volcanic eruption". London: TimesOnline. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- Kastljósið 22.3.2010, Sjónvarpið, "Viðtal við Dr. Pál Einarsson, jarðeðlisfræðing"

- "Newsnight – Olafur Grimsson: Eruption is only 'small rehearsal'". BBC News. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Weekly Reports". Katla. Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program.

- "Stamps created from Eyjafjallajokull volcano ash". FindYourStampsValue.com. 2010-07-30. Retrieved 2019-06-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eyjafjallajökull. |

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Eyjafjallajökull in the Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes

- Photos

- Satellite image of 2010 eruption by NASA

- A collection of satellite images from the CIMSS Satellite Blog

- Best of Photo Collection

- More from Eyjafjallajökull – The Big Picture

- Videos and webcams

- Webcams of the eruption

- A short time-lapse from April 17, 2010. About 30 minutes played in 18 second.

- Video of the first 2010 eruption

- Video of the first 2010 eruption by Raw Iceland

- Video of the aftermath of Eyjafjallajokull eruption. Shot on July 28, 2010

- A film crew lands on Eyjafjallajokull during the 2010 eruption

- Audio

- Geological articles

- Sturkell, Erik; Einarsson, Páll; Sigmundsson, Freysteinn; Hooper, Andy; Ófeigsson, Benedikt G.; Geirsson, Halldór; Ólafsson, Halldór (2010). "Geology of Katla and Eyjafjallajökull volcanoes, University of Iceland". Developments in Quaternary Sciences: 5–21. doi:10.1016/S1571-0866(09)01302-5.

- Magma pathways and earthquakes at Eyjafjallajökull, Icelandic Meteorological Institute (PDF)

- SI / USGS Weekly Volcanic Activity Report for Eyjafjallajökull

- Aviation ash forecasts

- Maps