Euthydemus I

Euthydemus I (Greek: Εὐθύδημος Α΄; c. 260 BC – 200/195 BC) was a Greco-Bactrian king in about 230 or 223 BC according to Polybius;[1] he is thought to have originally been a satrap of Sogdiana who overturned the dynasty of Diodotus of Bactria and became a Greco-Bactrian king. Strabo, on the other hand, correlates his accession with internal Seleucid wars in 223–221 BC. His kingdom seems to have been substantial, including probably Sogdiana to the north, and Margiana and Ariana to the south or east of Bactria.

| Euthydemus I | |

|---|---|

Coin with Greek inscription reads: ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ ΘΕΟΥ i.e. "of Euthydemus God", Euthydemus qualified as "THEOS" ("God"). (Pedigree coin of Agathocles of Bactria.) | |

| Greco-Bactrian king | |

| Reign | 230–200/195 BC |

| Predecessor | Diodotus II or Antiochus Nikator |

| Successor | Demetrius I |

| Born | c. 260 BC Magnesia |

| Died | 200 or 195 BCE Bactria |

| Spouse | A sister of Diodotus II |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Euthydemid |

| Father | Antimachus |

Biography

Euthydemus was allegedly a native of Magnesia (though the exact site is unknown), son of the Greek general Apollodotus, born c. 295 BC, who might have been son of Sophytes, and by his marriage to a sister of Diodotus II and daughter of Diodotus I, born c. 250 BC, was the father of Demetrius I according to Strabo[2] and Polybius;[3] he could possibly have had other royal descendants, such as sons Antimachus I, Apollodotus I and Pantaleon.

- For Euthydemus himself was a native of Magnesia, and he now, in defending himself to Teleas, said that Antiochus was not justified in attempting to deprive him of his kingdom, as he himself had never revolted against the king, but after others had revolted he had possessed himself of the throne of Bactria by destroying their descendants. (...) finally Euthydemus sent off his son Demetrius to ratify the agreement. Antiochus, on receiving the young man and judging him from his appearance, conversation, and dignity of bearing to be worthy of royal rank, in the first place promised to give him one of his daughters in marriage and next gave permission to his father to style himself king. (Polybius, 11.34, 2 )

War with the Seleucid Empire

Little is known of his reign until 208 BC when he was attacked by Antiochus III the Great, whom he tried in vain to resist on the shores of the river Arius (Battle of the Arius), the modern Herirud. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a battle on the Arius [3] and had to retreat. He then successfully resisted a three-year siege in the fortified city of Bactra, before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son Demetrius around 206 BC.[3] As part of the peace treaty, Antiochus was given Indian war elephants by Euthydemus.[4]

Classical accounts also relate that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the descendants of the original rebel Diodotus, and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts:

- "...for if he did not yield to this demand, neither of them would be safe: seeing that great hords of Nomads were close at hand, who were a danger to both; and that if they admitted them into the country, it would certainly be utterly barbarised." (Polybius, 11.34).

The war lasted altogether three years and after the Seleucid army left, the kingdom seems to have recovered quickly from the assault. The death of Euthydemus has been roughly estimated to 200 BC or perhaps 195 BC, and the last years of his reign probably saw the beginnings of the Bactrian incursions into Northern India.

Coinage

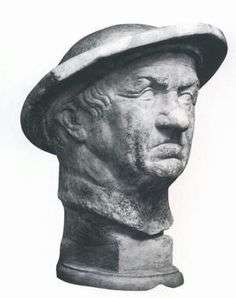

There exist many coins of Euthydemus, portraying him as a young, middle-aged and old man. He is also featured on no less than three commemorative issues by later kings, Agathocles, Antimachus I and one anonymous series.[5] He was succeeded by Demetrius, who went on to invade northwestern regions of South Asia. His coins were imitated by the nomadic tribes of Central Asia for decades after his death; these imitations are called "barbaric" because of their crude style.

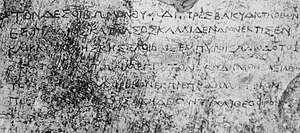

Kuliab inscription

In an inscription found in the Kuliab area of Tadjikistan, in western Greco-Bactria, and dated to 200-195 BC,[6] a Greek by the name of Heliodotos, dedicating a fire altar to Hestia, mentions Euthydemus as the greatest of all kings, and his son Demetrius I as "Demetrios Kalinikos" "Demetrius the Glorious Conqueror":[7][6]

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Greek script) | Inscription (Greek language) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

References

- Polybius. The Histories. Book XI chap. 34 v. 1.

- Strabo, Geography 11.11.1

- Polybius 11.34 Siege of Bactra

- Polybius. Histories.

adding to his own the elephants belonging to Euthydemus.

- "Two Remarkable Bactrian Coins" RC Senior, Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter 159

- Shane Wallace Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries p.206

- Osmund Bopearachchi, Some Observations on the Chronology of the Early Kushans, p.48

- Shane Wallace Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries p.211

- Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum: 54.1569

External links

- Coins of Euthydemus

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

| Preceded by Diodotus II or Antiochus Nikator |

Greco-Bactrian Ruler 230 – c. 200 BCE |

Succeeded by Demetrius I |

- O. Bopearachchi, "Monnaies gréco-bactriennes et indo-grecques, Catalogue raisonné", Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1991, p.453

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2 April 2019). "History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE". BRILL – via Google Books.