Kharahostes

Kharahostes or Kharaostasa was an Indo-Scythian ruler (probably a satrap) in the northern Indian subcontinent around 10 BCE – 10 CE. He is known from his coins, often in the name of Azes II, and possibly from an inscription on the Mathura lion capital, although another satrap Kharaostes has been discovered in Mathura.[2]

| Kharahostes | |

|---|---|

| Indo-Scythian king | |

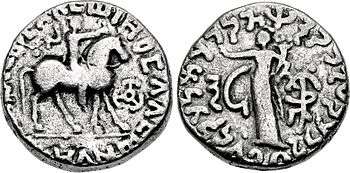

Coin of Kharahostes (or possibly his son Mujatria),[1] in the name of Azes. Obv. Azes riding, with corrupted Greek legend (WEIΛON WEOΛΛWN IOCAAC) for ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΑΖΟΥ "King of Kings Azes", and Buddhist Triratna symbol behind the head of the king. Rev. City goddess Tyche standing left holding cornucopia and raised right hand. Kharoshthi legend Maharajasa mahatasa Dhramakisa Rajatirajasa Ayasa "The Great king followower of the Dharma, King of Kings Azes" | |

| Reign | 10 BCE – 10 CE |

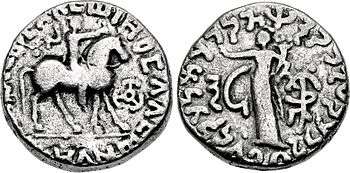

Obverse: King on horseback, with levelled spear. Greek legend XAPAHWCTEI ϹΑΤΡΑΠΕΙ ARTAYOY ("Satrap Kharahostes, son of Arta"). Kharoahthi mint mark sam

Reverse: Lion. Kharoshthi legend Chatrapasa pra Kharaustasa Artasa putrasa ("Satrap Kharahostes, son of Arta").

He was probably a successor of Azes II. Epigraphical evidence from inscribed reliquaries show for certain that he was already "Yabgu-King", when the Indravarman Silver Reliquary was dedicated, which is itself positioned with certainty before the 5-6 CE Bajaur casket.[3] There is some dispute however about the exact meaning of Yabgu-King. For Richard Salomon, Yabgu means "tribal chief", in the manner of the Kushans, suggesting that Kharahostes was already fully king by the end of the 1st century BCE, supporting a 10 BCE- 10 CE date for his reign. For Joe Cribb, this is a misspelling by a careless scribe, and should be read "yuva-King" which means "Heir apparent", and therefore would push forward the years Kharahostes actually ruled to the first part of the 1st century CE.[4]

Coin finds suggest that Kharahostes ruled in the area of the Darunta district to the west of Jalalabad, probably based on the ancient city of Nagarahara, located to the west of Jalalabad.[5]

Son of Arta

Kharahostes's own coins attest that he was the son of Arta, a brother of king Maues,[6] and Satrap of Chukhsa.[7]

According to F. W. Thomas and Hendrik Willem Obbink, his mother was Nada Diaka, who was the daughter of Ayasia Kamuia.[8][9] However, according to Sten Konow, Ayasia Kamuia, the chief queen of Rajuvula, was the daughter of Kharahostes.[10]

Kharohostes' coinage bears a dynastic mark (a circle within three pellets), which is rather similar, although not identical, with the dynastic mark of the Kushan ruler Kujula Kadphises (three pellets joined together), which has led to suggestions that they may have been contemporary rulers.

The Kharaosta of the Mathura lion capital inscriptions is usually identified with the Satrap Kharaostas or Kharahostes.[11] However, according to a recent study by Joe Cribb, the Kharaostes of Mathura should be considered as a different Indo-Scythian Northern Satrap, who ruled in Mathura with his own specific coinage and was probably a successor of Sodasa just before the conquest of Mathura by Kushan king Vima Takto.[5]

Kharaosta's known coins are of two types, presenting legends in Greek characters on the obverse and in Kharoshthi in the reverse: a round type in the name of Azes and three-pellet symbol, also recently attributed to his son Mujatria, and a square type without the three-pellet symbol in his own name, as son of Arta.

The Greek and Kharoshthi legends in the square coins run thus:

XAPAHWCTEI ϹΑΤΡΑΠΕΙ ARTAYOY (Greek for "Satrap Kharahostes, son of Arta")

Kṣatrapasa Pra Kharaoṣtasa Artasa Putrasa (Kharoshthi for "Satrap Kharaosta, son of Arta")[12]

Some of his coins write "Ortas" in place of "Artas".

Buddhist dedications

Kharahostes is known for several Buddhist dedications.

Bimaran casket

Unworn coins of Kharahostes, or his son Mujatria, were found in the Bimaran casket, suggesting the dedication was made during his rule or that of his son, if not by them personally.[5]

Indravarman's Silver Reliquary

Kharahostes is also known as one of the owners of the Indravarman's Silver Reliquary as described by the inscriptions in Kharoshthi on the reliquary.[13] He was probably the initial owner of the reliquary, which was then rededicated by Apraca ruler Indravarma. The Indravarman Silver Reliquary is dated with certainty before the Bajaur casket, meaning it must have been dedicated by Indravarman as a Prince in the end of the 1st century BCE, implying that Kharahostes, the previous owner of the Silver Reliquary (as shown by the inscriptions) was already king before that time (at the very least before 6 CE, date of the Bajaur casket).[3][14]

A son: Mujatria

Some rare square coins, also displaying the three-pellet symbol, were struck in the name of Mujatria, who claims in the Kharoshthi legends of these coins that he is the "son of Kharahostes".[5]

A recent study (2015) by Joe Cribb suggests that the round debased silver coins with three-pellet symbols in the name of Azes, usually attributed to Kharahostes, should actually be attributed to Mujatria.[1]

See also

- Parama-Kambojas

- India and Central Asia

References and notes

- Dating and Locating Mujatria and the two Kharaostes, Joe Cribb, 2015, p.43-44, type 11a

- Joe Cribb

- An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman, Richard Salomon, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 116, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1996), pp. 442

- Joe Cribb, p.31

- "Dating and locating Mujatria and the two Kharahostes", by Joe Cribb, 2015, p.27-28

- Ahmad Hasan Dani (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations, 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-208-1408-0. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Taxila an illustrated account of archaeological excavations, CUP Archive

- Hendrik Willem Obbink (1949). Orientalia Rheno-traiectina. Brill Archive. p. 333. GGKEY:S6C77GP5KP7. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- F. W. Thomas, Epigraphia Indica, Vol IX, p 135, F. W. Thomas.

- Sten Konow, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part I, p 36 & xxxvi

- Ahmad Hasan Dani et al., History of Civilizations of Central Asia, 1999, p 201, Unesco

- Philologica indica, 1940, p 252, Dr Heinrich Lüders

- Inscription Nb II in Apracaraja Indravarman's Silver Reliquary

- Richard Salomon, "An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 116, No. 3 (July - September 1996), pp. 418-452