Ethnic groups in Senegal

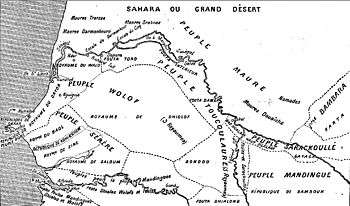

There are various ethnic groups in Senegal, none of which forms the ethnic majority in the country. Many subgroups of those can be further distinguished, based on religion, location and language. According to one 2005 estimate, there are at least twenty distinguishable groups of largely varying size.[1]

Major groups

- The largest group is the Wolof, representing 43.3% of the population of the country.[2] They live predominantly in the west, having descended from the kingdoms of Cayor, Waalo and Jolof that once existed in that area. Their population is focused in large urban centres. Most are Muslim, being either Mouride or Tijānī. The Lebou people of Cap-Vert and Petite Côte are considered a subgroup of the Wolof, however they represent less than 1% of its population.[3] The prevalence of the Wolof both linguistically and politically has continued to increase throughout the years; this tendency has been called the "wolofisation" of Senegal.[4]

- The Fula, those who speak the Fula language, are the second most populous group, representing 23.8% of the country's population.[5] This figure includes the Toucouleurs, but according to surveys, this subgroup is sometimes considered separate from the Fula. They were Islamized very early. The territory inhabited by the Fula is larger than that of the Wolof, however many areas are sparsely populated, such as Ferlo, Kolda, the Senegal River Valley, and Badiar. Traditionally nomadic, the vast majority has become sedentary, although there is a current rural exodus. Since Ahmed Sékou Touré became president of Guinea, many Guinean Fula have immigrated to Senegal, particularly from Fouta Djallon.

- The third group is the Serer, who represent 14.7% of the national population.[6] Serer pre-colonial kingdoms included : the Kingdom of Sine, Kingdom of Saloum, Biffeche and previously the Kingdom of Baol (ruled by the Joof family). Serer medieval history is characterized by resisting Islamization from the 11th century (during the Almoravids' advance) to the 19th century (the Marabout wars of Senegambia), resulting in the Battle of Fandane-Thiouthioune, commonly known as the Battle of Somb. The Serer anti-French movement during the colonial era resulted in the Battle of Logandème. The Serer people includes, but not limited to : the Saafi, Ndut, Laalaa, Niominka, Palor, etc. Many of these speak the Cangin languages.

- The Jola represent 5% of the country's population, and mostly live in Ziguinchor where they primarily make their living from rice cultivation and fishing. Traditionally animist, they have historically resisted the spread of both Islam and Christianity in the country.[7] While much of the Jola population now adheres to either Islam or Christianity, many mix these religions with animist beliefs. The Jola hold their ethnic distinctiveness as of great importance.[8]

Avenue du Senegal in Tyre, Lebanon

Avenue du Senegal in Tyre, Lebanon - Other groups also live in the Ziguinchor Region. While these groups lead lifestyles that are very similar to the Jola, they speak different languages and are much less populous. This is the case of the Bainuk, the Balanta, the Manjack, the Mankanya, the Karoninka, and the Bandial.

- Several small ethnic groups in Senegal are related to the Mandinka, together constituting 4% of the population of the country. These include the Malinké, the Sossé, the Bambara, the Dyula, the Yalunka, and the Jakhanke.

- The Soninke represent 0.5% of the population of Senegal. While most of the Soninke live in Mali, some live on the other side of the border, along the Falémé and Sénégal Rivers. This group has been experiencing a significant diaspora. The Soninke were Islamized earlier than most other groups in the country.

A few Bassari and Bedick live in the hills in eastern Senegal around Kédougou. These are subgroups of the Tenda, same as the Coniagui and the Badiaranké.

- Senegal has among its population many Africans from other countries. There are small Ivorian communities in Dakar, as well as many Nigerians, most of which being Hausa. Malians go almost unnoticed in Senegal because their culture is so similar to that of the Senegalese. There is a large Cape Verdean community in Dakar. Moors, constituting 0.5% of the population of Senegal, have long invested in business in the country, residing mainly in cities in the north. The subgroup of the Darmankour, who have lived in Senegal for centuries, are present throughout the country.

Europeans and descendants of Lebanese migrants are fairly numerous in urban centres in Senegal, about 50,000. Most of the Lebanese originate from the Southern Lebanese city of Tyre, which is known as "Little West Africa and has a main promenade that is called "Avenue du Senegal".[9]

Minor groups

There are also many other smaller representations of other ethnic groups in Senegal, including the Khassonké, the Lawbe and the Papel.

There are also small Chinese and Vietnamese migrant communities.

Commonality

The predominant ethnic groups in Senegal share a common cultural background so that, apart from their languages that also have many similarities, there are no effective cultural barriers between them. This is why marriage between ethnic groups in Senegal is so common.

See also

Related articles

- Languages of Senegal

- List of African ethnic groups

Bibliography

- Mara A. Leichtman (2005). "The legacy of transnational lives: Beyond the first generation of Lebanese in Senegal". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 28 (4): 663–686. doi:10.1080/13569320500092794.

- Papa Oumar Fall, «The ethnolinguistic classification of Seereer in question», in Altmayer, Claus / Wolff, H. Ekkehard, Les défis du plurilinguisme en Afrique, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2013, pp. 47–60

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethnic groups of Senegal. |

- (in French) The ethnic groups of Senegal

References

- Atlas du Sénégal (in French). Paris: Éditions J. A. 2007. pp. 72–73.

- "The World Factbook:Senegal". CIA. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Peuples du Sénégal (in French). Éditions Sépia. 1996. p. 182.

- Donal Cruise O'Brien (1979). "Langues et nationalité au Sénégal. L'enjeu politique de la wolofisation". Année Africaine (in French): 319–335.

- "The World Factbook:Senegal". CIA. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "The World Factbook:Senegal". CIA. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Christian Roche (2000). Histoire de la Casamance : Conquête et résistance 1850-1920 (in French). Karthala. p. 408. ISBN 978-2-86537-125-9.

- Jean-Claude Marut (2002). Le problème casamançais est-il soluble dans l'Etat-nation?. Le Sénégal Contemporain (in French). Paris: Karthala. pp. 425–458. ISBN 978-2-84586-236-4.

- Leichtman, Mara (2015). Shi'i Cosmopolitanisms in Africa: Lebanese Migration and Religious Conversion in Senegal. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 26, 31, 51, 54, 86. ISBN 978-0253015990.