Epidemiology of attention deficit hyperactive disorder

ADHD is estimated to affect about 6 to 7 percent of people aged 18 and under when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria.[1] Hyperkinetic disorder when diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria give rates of between 1 and 2 percent in this age group.[2]

Children in North America appear to have a higher rate of ADHD than children in Africa and the Middle East - however, this may be due to differing methods of diagnosis used in different areas of the world.[3] If the same diagnostic methods are used rates are more or less the same between countries.[4]

Africa

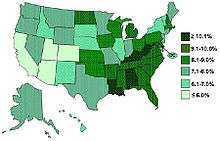

It is estimated that ADHD affects between 5.4-8.7% of children in Africa.[5] Data quality however is not high.[5]

Germany

A 2008 evaluation of the “KiGGS” survey, monitoring 14,836 girls and boys (age between 3 and 17 years), showed that 4.8% of the participants had an ADHD diagnosis. While 7.9% of all boys had ADHD, only 1.8% girls had it, too. Another 4.9% of the participants (6.4% boys : 3.6% girls) were suspected ADHD cases, because they showed a rate ≥7 on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scale. The number of ADHD diagnoses was 1.5% (2.4% : 0.6%) among preschool children (3–6 years old), 5,3 % (8.7% : 1.9%) at age 7–10 years, and had its peak at 7.1% (11.3% : 3.0%) in the age group of 11–13 years. Among 14 to 17 years old adolescents the rate was 5.6% (9.4% : 1.8%).[6]

Spain

Rates in Spain are estimated at 6.8% among people under 18.[7]

United Kingdom

In some parts of England there were waiting lists of five years or more for ADHD adult diagnostic assessment in 2019.[8]

United States

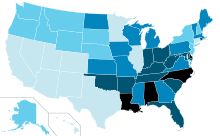

In the United States it is diagnosed in 2-16 percent of school children.[10] The rates of diagnosis and treatment of ADHD are much higher on the east coast of the United States than on its west coast.[11] The frequency of the diagnosis differs between male children (10%) and female children (4%) in the United States.[12] This difference between genders may reflect either a difference in susceptibility or that females with ADHD are less likely to be diagnosed than males.[13] Boys outnumber girls across all three subtyping categories, but the exact magnitude of these differences seems to depend on both the informant (parent, teacher, etc.) and the subtype. In two community-based investigations, conducted by DuPaul and associates, boys outnumbered girls by only 2.2:1 in parent-generated samples and 2.3:1 in teacher-based input.[14]

Changing rates

Rates of ADHD diagnosis and treatment have increased in both the United Kingdom and the United States since the 1970s. This is believed to be primarily due to changes in how the condition is diagnosed[15] and how readily people are willing to treat it with medications rather than a true change in the frequency.[2] In the UK an estimated 0.5 per 1,000 children had ADHD in the 1970s, while 3 per 1,000 received ADHD medications in the late 1990s. In the UK in 2003, 3.6 percent of male children and less than 1 percent in female children had the diagnosis.[16]:134 In the United States the number of children with the diagnosis increase from 12 per 1000 in the 1970s to 34 per 1000 in the late 1990s,[16] to 95 per 1,000 in 2007,[17] and 110 per 1,000 in 2011.[18] It is believed that the changes to the diagnostic criteria in 2013 from the DSM 4TR to the DSM 5 will increase the number of people with ADHD especially among adults.[19]

References

- Willcutt EG (July 2012). "The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (3): 490–9. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8. PMC 3441936. PMID 22976615.

- Cowen, Philip (2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 546. ISBN 9780191626753. Retrieved 2014-01-17. Cited source of Cowen (2012): Taylor, Eric (2012). "Attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorders in childhood and adolescence". New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (2nd ed.). pp. 1644–1654. doi:10.1093/med/9780199696758.003.0215. ISBN 9780199696758.

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA (June 2007). "The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (6): 942–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.942. PMID 17541055.

- Jones, edited by Ming Tsuang, Mauricio Tohen, Peter B. (2011-03-25). Textbook of psychiatric epidemiology (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 450. ISBN 9780470977408.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bakare, MO (September 2012). "Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and disorder (ADHD) among African children: a review of epidemiology and co-morbidities". African Journal of Psychiatry. 15 (5): 358–61. doi:10.4314/ajpsy.v15i5.45. PMID 23044891.

- "Erkennen – Bewerten – Handeln: Zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland" (PDF) (in German). Robert Koch Institute. 27 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF; 3,27 MB) on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2014. – Kapitel 2.8 Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS), S. 57 ISBN 978-3-89606-109-6. See also R. Schlack; et al. (23 April 2007). "Die Prävalenz der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland" (PDF) (in German). Robert Koch Institute. Archived from the original (PDF; 611 kB) on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Catalá-López, F; Peiró, S; Ridao, M; Sanfélix-Gimeno, G; Gènova-Maleras, R; Catalá, MA (Oct 12, 2012). "Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in Spain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies". BMC Psychiatry. 12: 168. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-168. PMC 3534011. PMID 23057832.

- "Clearing ADHD caseload could take 5 years, CCG warns". Health Service Journal. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "CDC – ADHD, Prevalence – NCBDDD". 2017-02-13.

- Rader, R; McCauley, L; Callen, EC (Apr 15, 2009). "Current strategies in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". American Family Physician. 79 (8): 657–65. PMID 19405409.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (October 17, 2013). "ADHD Home". United States: CDC.gov.

- CDC (March 2004). "Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002" (PDF). Vital and Health Statistics. United States: CDC. 10 (221).

- Staller J, Faraone SV (2006). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: epidemiology and management". CNS Drugs. 20 (2): 107–23. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620020-00003. PMID 16478287.

- Anastopoulos AD, Shelton, TL (2001). Assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "ADHD Throughout the Years" (PDF). Center For Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (24 September 2008). "CG72 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): full guideline" (PDF). NHS.

- "Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Data and Statistics". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2013.

- Schwarz, Alan (Mar 31, 2013). "A.D.H.D. Seen in 11% of U.S. Children as Diagnoses Rise". New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Dalsgaard, S (February 2013). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 22 Suppl 1: S43-8. doi:10.1007/s00787-012-0360-z. PMID 23202886.

External links