Epidemiology of tuberculosis

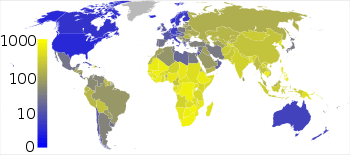

Roughly one-quarter of the world's population has been infected with M. tuberculosis,[4] and new infections occur at a rate of one per second.[5] However, not all infections with M. tuberculosis cause tuberculosis disease and many infections are asymptomatic.[6] In 2007 there were an estimated 13.7 million chronic active cases,[7] and in 2017 there were 10 million new cases, and 1.6 million deaths, mostly in developing countries.[4] 300 000 deaths occurred in those co-infected with HIV.[4]

|

no data

≤ 10

10–25

25–50

50–75

75–100

100–250

|

250–500

500–750

750–1000

1000–2000

2000–3000

≥ 3000

|

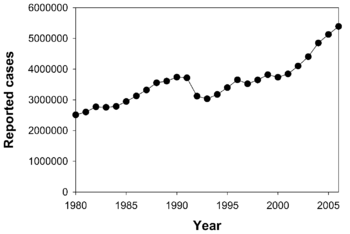

Tuberculosis is the most common cause of death from "a single infectious agent (above HIV/AIDS)".[4] The absolute number of tuberculosis cases has been decreasing since 2005 and new cases since 2002.[8] Russia has achieved particularly dramatic progress with decline in its TB mortality rate—from 61.9 per 100,000 in 1965 to 2.7 per 100,000 in 1993;[9][10] however, mortality rate increased to 24 per 100,000 in 2005 and then recoiled to 11 per 100,000 by 2015.[11] The distribution of tuberculosis is not uniform across the globe; about 80% of the population in many African, Caribbean, south Asian, and eastern European countries test positive in tuberculin tests, while only 5–10% of the U.S. population test positive.[12]

In 2017, the country with the highest estimated incidence rate as a % of the population was Lesotho, with 665 cases per 100,000 people.[4] As of 2017, India had the largest total incidence, with an estimated 2 740 000 cases.[4] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2000-2015, India's estimated mortality rate dropped from 55 to 36 per 100 000 population per year with estimated 480 thousand people died of TB in 2015.[13][14]

In developed countries, tuberculosis is less common and is mainly an urban disease. In Europe, deaths from TB fell from 500 out of 100,000 in 1850 to 50 out of 100,000 by 1950. Improvements in public health were reducing tuberculosis even before the arrival of antibiotics, although the disease remained a significant threat to public health, such that when the Medical Research Council was formed in Britain in 1913 its initial focus was tuberculosis research.[15]

In 2017, in the United Kingdom, the national average was 9 per 100,000 and the highest incidence rates in Western Europe were 20 per 100,000 in Portugal. These rates compared with 63 per 100,000 in China and 44 per 100,000 in Brazil. In the United States, the overall tuberculosis case rate was 3 per 100,000 persons in 2017.[4] In Canada, tuberculosis is still endemic in some rural areas.[16]

The incidence of TB varies with age. In Africa, TB primarily affects adolescents and young adults.[17] However, in countries where TB has gone from high to low incidence, such as the United States, TB is mainly a disease of older people, or of the immuno-compromised.[12][18]

Tuberculosis incidence is seasonal, with peaks occurring every spring/summer.[19][20][21][22] The reasons for this are unclear, but may be related to vitamin D deficiency during the winter.[22][23]

References

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- World Health Organization (2009). "The Stop TB Strategy, case reports, treatment outcomes and estimates of TB burden". Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. pp. 187–300. ISBN 9789241563802. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- World Health Organization. "WHO report 2008: Global tuberculosis control". Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- "Global Tuberculosis Report 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- "Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104". World Health Organization. November 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Fact Sheets: The Difference Between Latent TB Infection and Active TB Disease". Centers for Disease Control. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- World Health Organization (2009). "Epidemiology" (PDF). Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. pp. 6–33. ISBN 9789241563802. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- "The sixteenth global report on tuberculosis" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-06.

- Vladimir M. Shkolnikov and France Meslé. The Russian Epidemiological Crisis as Mirrored by Mortality Trends, Table 4.11, The RAND Corporation.

- Global Tuberculosis Control, World Health Organization, 2011.

- WHO global tuberculosis report 2016. Annex 2. Country profiles: Russian Federation

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 516–522. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- WHO Global tuberculosis report 2016: India

- "Govt revisits strategy to combat tuberculosis". Daily News and Analysis. 8 Apr 2017.

- Medical Research Council.Origins of the MRC. Accessed 7 October 2006.

- Al-Azem A, Kaushal Sharma M, Turenne C, Hoban D, Hershfield E, MacMorran J, Kabani A (1998). "Rural outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Canadian province". Abstr Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 38: 555. abstract no. L-27. Archived from the original on 2011-11-18.

- World Health Organization. "Global Tuberculosis Control Report, 2006 – Annex 1 Profiles of high-burden countries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (12 September 2006). "2005 Surveillance Slide Set". Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- Douglas AS, Strachan DP, Maxwell JD (1996). "Seasonality of tuberculosis: the reverse of other respiratory diseases in the UK". Thorax. 51: 944–946. doi:10.1136/thx.51.9.944. PMC 472621. PMID 8984709.

- Martineau AR, Nhamoyebonde S, Oni T, Rangaka MX, Marais S, et al. (2011). "Reciprocal seasonal variation in vitamin D status and tuberculosis notifications in Cape Town, South Africa". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108: 19013–19017. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111825108. PMC 3223428. PMID 22025704.

- Parrinello CM, Crossa A, Harris TG (2012). "Seasonality of tuberculosis in New York City, 1990–2007". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 16: 32–37. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0145.

- Korthals Altes H, Kremer K, Erkens C, Van Soolingen D, Wallinga J (2012). "Tuberculosis seasonality in the Netherlands differs between natives and non-natives: a role for vitamin D deficiency?". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 16: 639–644. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0680.

- Koh GCKW; Hawthorne G; Turner AM; Kunst H; Dedicoat M (2013). "Tuberculosis incidence correlates with sunshine: an ecological 28-year time series study". PLoS ONE. 8: e57752. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057752. PMC 3590299. PMID 23483924.