Endell Street Military Hospital

Endell Street Military Hospital was a First World War military hospital located on Endell Street in Covent Garden, central London. This was the only hospital entirely staffed by suffragists (women who supported the introduction of votes for women).

| Endell Street Military Hospital | |

|---|---|

Entrance to Endell Street Military Hospital, c. 1915 | |

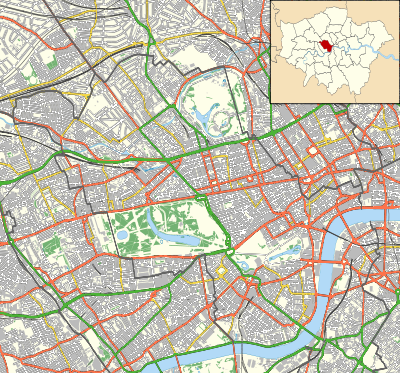

Location within Westminster | |

| Geography | |

| Location | 36, Endell Street, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51.5154°N 0.1255°W |

| Organisation | |

| Funding | Public hospital |

| Type | Military hospital |

| Services | |

| Beds | 573 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1915 |

| Closed | 1919 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in England |

The hospital was established during the First World War in May 1915[1] by Doctors Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson.[2] Both women were former members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a militant organisation that campaigned for women's suffrage in the early twentieth century.[2] The hospital was run under the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) of the British Army.[2]

History

Hospital

The hospital was established in May 1915[1] by Doctors Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson.[2] It was constructed in the former St Giles Union Workhouse located on Endell Street in Covent Garden, Central London. The empty workhouse had room for a larger hospital to operate. A majority of the hospital equipment came from a military hospital in Wimereux, France following its closure in January 1915. Murray and Anderson previously headed this hospital which was shut down because of a lack of patients as well as a destination change for injured soldiers from France to England.[1]

Endell Street Hospital had 573 beds, allowing for some 26,000 patients to be cared for during the five years the hospital was active. The women doctors performed upwards of 7,000 operations during that time.[3]

The hospital was located in close proximity to London's main railway stations, allowing a great influx of patients when ambulance convoys arrived. Often each convoy was transporting 30 to 50 injured soldiers, some of which required immediate surgery. These soldiers were taken directly to the operating theatre.[2] The doctors were able to carry out as many as 20 operations a day, many of which were late at night when the convoys arrived.[3]

A small ward for service women was opened, late in the hospital's life.[4]

Staff

Endell Street Military Hospital was staffed entirely by suffragettes. Leading the hospital, Murray was named Doctor in Charge and Anderson was named Chief Surgeon. Many of the women who staffed the hospital had previously worked with Murray and Anderson at the hospital in Wimereux. When that hospital closed its doors, the suffragettes were relocated to the new Endell Street hospital.[1] At Endell Street, these women worked in what was considered female-appropriate jobs as nurses, orderlies, and clerks. The hospital also staffed women as drivers, dentists, pathologists, and surgeons, which tended to be considered more masculine employment.[2]

The hospital also received a great number of volunteers daily. Librarians and entertainment officers would visit with the patients to heighten morale. Gardeners would help in the courtyard and ward visitors would often come, some only wishing to visit with lonely patients as they did not have family or friends in the hospital.[5]

Women's Hospital Corps

The concept of the Women's Hospital Corps was created and instituted in 1914. Previously met with hostility by officials, Murray and Anderson decided to bypass the British government by going directly to the French Embassy with their offer to run a military hospital in France. Their idea was accepted and they were granted work permits to travel to France. In less than two weeks, Murray and Anderson were able to recruit enough medically trained women to staff an entire hospital; doctors, nurses, orderlies, and clerks. The women created uniforms and raised funds for the supplies needed.[5]

While working under the authority of the War Office, women doctors at the Endell Street Military Hospital received the pay and benefits of military grades from lieutenant to lieutenant colonel, but they had no rank and could not command men.[6]

The Women's Social and Political Union influence at Endell Street Military Hospital

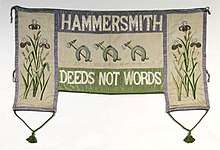

Although the hospital was run by suffragettes, the women kept the suffrage movement and their hospital duties separate. The hospital did, however, adopt the WSPU's motto of "Deeds, Not Words". In the long run, the women hoped that the hospital and their deeds would prove women's equality and their ability to fulfil their duties as citizens.[2]

Tension with the Royal Army Medical Corps

The RAMC was outspoken about their reluctance to allow an all women's staff run a military hospital. The staff's involvement in the suffrage movement also added to the RAMC's scepticism of the women's ability perform in a professional manner. Murray recounts a colonel who was disgusted by the idea, claiming that the hospital would shut down within six months.[1] The RAMC felt that the women would not be properly trained to care for and control soldiers in the military setting. They were proven wrong when the women received all positive acknowledgments due to their feminine touches around the hospital. Flowers, bright colours, and proper lighting were all attributed to the women's ability to consider the patient's psychological health as well as their physical health.[2]

Contributions

During the hospital's active years, Endell Street Military Hospital staff were able to publish a total of seven publications in The Lancet, one of the world's oldest and best known general medical journals.[7] The papers were in collaboration with the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service. They included an analysis of a series of cases of anaerobic infection, and collaborated with the Institute Pasteur in trials of gas gangrene antiserum by Frances Ivens from the Scottish Women's Hospital at Royaumont. Endell Street and Royaumont together produced the first hospital-based research papers published by female British doctors.[2]

1918 flu pandemic

The Endell Street Military Hospital received patients affected by the 1918 flu pandemic that infected 500 million people across the world.[6]

Closure

In 1917, Murray and Anderson each received the CBE for their work in the hospital.[3] In October 1919, Endell Street received orders to evacuate and close the hospital. Endell Street Military Hospital closed its doors in December 1919.[1][8]

References

- Murray, Flora (1920). Women as Army Surgeons: Being the history of the Women's Hospital Corps in Paris, Wimereux, and Endell Street September 1914-October 1919. London: Hodder & Stoughton. A second copy at archive.org.

- Geddes, Jennian F (January 2007). "Deeds and words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street". Medical history. England. 51 (1): 79–98. doi:10.1017/s0025727300000909. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1712367. PMID 17200698.

Endell Street differed from other women’s hospitals of the First World War in that the staff made no secret of their militant views, and the public perceived it to be a specifically suffrage hospital. In forming the group, Murray and Anderson had left no ambiguity about their aims, and, explicitly linking their work with their political aspirations, committed themselves to educating and training the women under their command in their expectations and obligations as future citizens. Ironically, despite the overt feminism of the WHC, there is no doubt that by the end of the war the success of its hospital had played a considerable role in expunging the stigma of the militant years in the eyes of the public at large.

- "World War One: Endell Street hospital's suffragette surgeons". BBC News. 28 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- B. E. Escott. Women in Air Force Blue. p. 31.

- Geddes, Jennian F (1 May 2006). The Women's Hospital Corps: Forgotten Surgeons of the First World War. Journal of Medical Biography 14, no. 2. p. 109–17. ProQuest 210330818.

- Hacker, Barton C.; Vining, Margaret, eds. (17 August 2012). A Companion to Women's Military History. History of Warfare. 74. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20682-3. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- "Prestigious Medical Journal, The Lancet, Issues Family Planning Series". Population Media Center. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2016

- "Endell Street Military Hospital". Lost Hospitals of London. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

Further reading

- Moore, Wendy (2020). Endell Street: the suffragette surgeons of World War One. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781786495846

(also entitled: Endell Street: the Trailblazing Women who Ran World War One's Most Remarkable Military Hospital ISBN 9781786495860)

- Moore, Wendy. "Endell Street". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

External links

- Details of photograph of staff 1916 held at Senate House Library, London

- Endell Street, London: Only All-Female Run Military Hospital

- Geddes, J. F. (2008). "Louisa Garrett Anderson (1873-1943), surgeon and suffragette". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (4): 205–14. doi:10.1258/jmb.2007.007048. PMID 18952990.