Endell Street

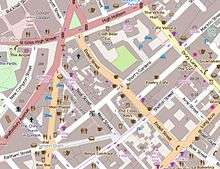

Endell Street, originally known as Belton Street, is a street in London's West End that runs from High Holborn in the north to Long Acre and Bow Street, Covent Garden, in the south. A long tall narrow building on the west side is an 1840s-built public house, the Cross Keys, Covent Garden.

Location

Endell Street is crossed only by Shorts Gardens and Shelton Street. Betterton Street intersects between these on the eastern side. The northern end of the street is in the London Borough of Camden, the south in the City of Westminster. The street is an avenue with very tall, mature plane trees, widely spaced; it now equals the B401 (which had included Bow and Wellington Streets) and is one-way, southbound.

History

The land on which the southern part of Endell Street is built was originally owned by William Short, who leased it to Esmé Stewart, 3rd Duke of Lennox, in 1623–24. Lennox House was built on the site which eventually passed to Sir John Brownlow who began to build from 1682. Belton Street was created, named after the Brownlow's country seat in Lincolnshire, Belton House.[1] Henry Wheatley writes that the southern end of the street from Castle Street to Short's Gardens was originally known as Old Belton Street, the northern end from Short's Gardens to St Giles, was known as New Belton Street.[2]

In the seventeenth century, Queen Anne is supposed to have bathed in the waters from a medical spring there at a site known as Queen Anne's Bath.[3]

The modern Endell Street was created according to the reforming plans of architect James Pennethorne.[4]

Charles Lethbridge Kingsford states that the street was built in 1846 when Belton Street was widened and extended northwards to Broad Street (now in High Holborn).[1] The street is believed to have been named after the Reverend James Endell Tyler, rector of St Giles in the Fields in the 1840s.[3] The British Lying-In Hospital was relocated to a purpose-built building on Endell Street in 1849.[5][6]

Listed buildings

There are eight listed buildings of the street, including:

Lavers and Barraud stained-glass studio

The Lavers and Barraud Building at 22 Endell Street, together with the attached cast-iron railings, is a Grade II listed building. The polychrome brick and stone building was designed as a studio for the stained-glass firm by R.J. Withers in 1859 in the Gothic style;[7] the gable window on Betterton Street has modern stained glass by Brian Clarke, commissioned by the Crafts Council in 1981.

Cross Keys public house

The Cross Keys public house at №31, constructed 1848-49, is a Grade II listed building.[8]

Latchfords Timber Yard

The nineteenth-century Latchfords Timber Yard and attached timber sheds at №61 are Grade II listed.[9]

Swiss Protestant Church

The Swiss Protestant Church at №79 was designed by George Vulliamy and built 1853-4. It is also Grade II listed.[10]

Inhabitants

The watercolour painter William Henry Hunt was born at "8 Old Belton Street" (№ 7) in 1790.[2]

Hospitals of Endell Street

British Lying-in Hospital

Founded in 1749, this maternity hospital was built at №24 in 1849;[11] it closed in 1913.[12]

St Paul's Hospital

Founded in 1898, thus urology hospital took over the premises at №24 after the British Lying-In Hospital closed; St Paul's Hospital closed in 1992.[13]

Endell Street Military Hospital

During the first world war a military hospital operated from №36, staffed entirely by women. The hospital was opened in 1915 by suffragists Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson and treated 24,000 patients and carried out over 7,000 operations. It closed in 1919.[14][15]

Clubs

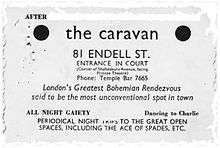

The Caravan Club

The basement of №81 was home from July 1934 to the Caravan Club that advertised itself as "London's Greatest Bohemian Rendezvous said to be the most unconventional spot in town" which was code for being gay-friendly. The club helpfully promised "All night gaiety".[16] It was run by Jack Rudolph Neaves, known as "Iron Foot Jack" on account of the metal leg brace he wore, and was frequented by both gay men and lesbian women. It was financed by small-time criminal Billy Reynolds.

The club came to the attention of the police almost straight away and in August local residents complained "It's absolutely a sink of iniquity."[17] The club was raided on 25 August, with men arrested. Their trial at Bow Street Magistrates Court caused a sensation reported in the News of the World.[18]

The Hospital Club

The Hospital Club opened in 2003 at №24 to serve the members of London's media and creative industries. It is on the site of the former St Paul's Hospital.[19]

References

- Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge. (1925). The early history of Piccadilly Leicester Square Soho & their neighbourhood based on a plan drawn in 1585 and published by the London Topographical Society in 1925. Cambridge: University Press. p. 35.

- Wheatley, Henry B. (1891). London past and present: Its history, associations, and traditions. I. London: John Murray. Cambridge University Press reprint, 2011. p. 157. ISBN 9781108028066.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2010). The London Encyclopaedia. London: Pan Macmillan. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

- "Commercial Street | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- "Information Leaflet Number 35 Records of patients in London hospitals" (PDF). London Metropolitan Archives. City of London. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Ryan, Thomas (1885). The History of Queen Charlotte's Lying-in Hospital. pp. ix–xv.

- Historic England. "NUMBER 22 AND ATTACHED RAILINGS (1078289)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Historic England. "CROSS KEYS PUBLIC HOUSE (1078290)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Historic England. "LATCHFORDS TIMBER YARD INCLUDING ATTACHED TIMBER SHEDS (1078292)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Historic England. "SWISS PROTESTANT CHURCH (1078294)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Waterston, Jane Elizabeth (1983). The Letters of Jane Elizabeth Waterston, 1866-1905. Van Riebeeck Society, The. ISBN 9780620073752.

- "British Lying-In Hospital". Lost Hospitals of London. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- St Paul’s Hospital for Skin and Genito-Urinary Diseases. "St Paul's Hospital for Skin and Genito-Urinary Diseases". www.ucl.ac.uk. UCL Bloomsbury Project. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Endell Street, London: Only All-Female Run Military Hospital. BBC, 3 February 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Hacker, Barton; Vining, Margaret. (Eds.) (2012). A Companion to Women's Military History. Brill. p. 193. ISBN 978-90-04-21217-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Houlbrook, Matt. (2006). Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918–1957. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-226-35462-0.

- Jennings, Rebecca. (2007). Tomboys and Bachelor Girls: A Lesbian History of Post-War Britain 1945–71. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7190-7544-5.

- Houlbrook, Matt (15 October 2006). Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226354620 – via Google Books.

- About Us. The Hospital Club. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

External links

![]()