Ember days

In the liturgical calendar of the Western Christian churches, ember days are four separate sets of three days within the same week—specifically, the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday—roughly equidistant in the circuit of the year, that are set aside for fasting and prayer. These days set apart for special prayer and fasting were considered especially suitable for the ordination of clergy. The Ember Days are known in Latin as the quatuor anni tempora (the "four seasons of the year"), or formerly as the jejunia quatuor temporum ("fasts of the four seasons").

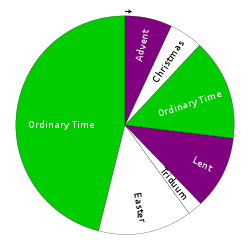

| Christian liturgical year |

|---|

| Western |

| Eastern |

|

| East Syriac Rite |

|

The four quarterly periods during which the ember days fall are called the embertides.

Etymology

Ember days have their origin in the Latin Quatuor Tempora (four times).[1]

There are various views as to etymology. According to J. M. Neale in Essays of Liturgiology (1863), Chapter X:

"The Latin name has remained in modern languages, though the contrary is sometimes affirmed, Quatuor Tempora, the Four Times. In French and Italian the term is the same; in Spanish and Portuguese they are simply Temporas. The German converts them into Quatember, and thence, by the easy corruption of dropping the first syllable, a corruption which also takes place in some other words, we get the English Ember. Thus, there is no occasion to seek after an etymology in embers; or with Nelson, to extravagate still further to the noun ymbren, a recurrence, as if all holy seasons did not equally recur. Ember-week in Wales is Welsh: "Wythnos y cydgorian", meaning "the Week of the Processions". In mediæval Germany they were called Weihfasten, Wiegfastan, Wiegefasten, or the like, on the general principle of their sanctity.... We meet with the term Frohnfasten, frohne being the then word for travail. Why they were named foldfasten it is less easy to say."

Neil and Willoughby in The Tutorial Prayer Book (1913) prefer the view that it derives from the Anglo-Saxon ymbren, a circuit or revolution (from ymb, around, and ryne, a course, running), clearly relating to the annual cycle of the year. The word occurs in such Anglo-Saxon compounds as ymbren-tid ("Embertide"), ymbren-wucan ("Ember weeks"), ymbren-fisstan ("Ember fasts"), ymbren-dagas ("Ember days"). The word imbren even makes it into the acts of the "Council of Ænham"[2] (1009): jejunia quatuor tempora quae imbren vocant, "the fasts of the four seasons which are called "imbren'".[3] It corresponds also with Pope Leo the Great's definition, jejunia ecclesiastica per totius anni circulum distributa ("fasts of the church distributed through the whole circuit of the year").

Folk etymology even cites the phrase "may ye remember (the inevitability of death)" as the source.

Origins

The term Ember days refers to three days set apart for fasting, abstinence, and prayer during each of the four seasons of the year.[4] The purpose of their introduction was to thank God for the gifts of nature, to teach men to make use of them in moderation, and to assist the needy.[1]

Possibly occasioned by the agricultural feasts of ancient Rome, they came to be observed by Christians for the sanctification of the different seasons of the year.[4] James G. Sabak argues that the Embertide vigils were "...not based on imitating agrarian models of pre-Christian Roman practices, but rather on an eschatological rendering of the year punctuated by the solstices and equinoxes, and thus underscores the eschatological significance of all liturgical vigils in the city of Rome."[5]

At first, the Church in Rome had fasts in June, September, and December. The Liber Pontificalis ascribes to Pope Callixtus I (217–222) a law regulating the fast, although Leo the Great (440–461) considers it an Apostolic institution. When the fourth season was added cannot be ascertained, but Pope Gelasius I (492–496) speaks of all four. The earliest mention of four seasonal fasts is known from the writings of Philastrius, bishop of Brescia (died ca 387) (De haeres. 119). He also connects them with the great Christian festivals.

As the Ember Days came to be associated with great feast days, they later lost their connection to agriculture and came to be regarded solely as days of penitence and prayer.[6] It is only the Michaelmas Embertide, which falls around the autumn harvest, that retains any connection to the original purpose.

The Christian observance of the seasonal Ember days had its origin as an ecclesiastical ordinance in Rome and spread from there to the rest of the Western Church. They were known as the jejunium vernum, aestivum, autumnale and hiemale, so that to quote Pope Leo's words (A.D. 440 - 461) the law of abstinence might apply to every season of the year. In Leo's time, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday were already days of special observance. In order to tie them to the fasts preparatory to the three great festivals of Christmas, Easter and Pentecost, a fourth needed to be added "for the sake of symmetry" as the Encyclopædia Britannica 1911 has it.

From Rome the Ember days gradually spread unevenly through the whole of Western Christendom. In Gaul they do not seem to have been generally recognized much before the 8th century.

Their observance in Britain, however, was embraced earlier than in Gaul or Spain, and Christian sources connect the Ember Days observance with Augustine of Canterbury, AD. 597, said to be acting under the direct authority of Pope Gregory the Great. The precise dates appears to have varied considerably however, and in some cases, quite significantly, the Ember Weeks lost their connection with the Christian festivals altogether. Spain adopted them with the Roman rite in the eleventh century. Charles Borromeo introduced them into Milan in the sixteenth century.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, ember days have never been observed. Yet in Western Rite Orthodoxy, which is in full communion with the Eastern Orthodox, the Ember days are observed.[1]

Ember Weeks

The Ember Weeks, the weeks in which the Ember Days occur, are these weeks:

- between the third and fourth Sundays of Advent (although the Common Worship lectionary of the Church of England places them in the week following the second Sunday in Advent); but because the calendar reform in the 1970s includes specific "Late Advent" propers for Dec 17 onward, when Ember Days were restored for the Personal Ordinariates, the Vatican assigned the Ember Days to the first week of Advent.

- between the first and second Sundays of Lent;

- between Pentecost and Trinity Sunday; and

- the liturgical Third Week of September. According to an old way of counting, the first Sunday of a month (a datum important to determine the appropriate Matins readings) was considered the Sunday proximate to, not on or after, the first of the month, so this yielded as Ember Week precisely the week containing the Wednesday after Holy Cross Day (September 14), and as Ember Days said Wednesday and the following Friday and Saturday. It has been preserved in that order by Western Rite Orthodoxy[7] and Anglicans.[8] Yet for Roman Catholics, a 20th-century reform of the Breviary shifted the First Sunday in September to what the name literally implies, and by implication, Ember Week to the Week beginning with the Sunday after Holy Cross day. Therefore, in a year that September 14 falls on a Sunday, Monday, or Tuesday, the Ember Days for Western Rite Orthodox and Anglicans are a week sooner than for those of modern-day Catholics. But when the Vatican restored the Ember Days for the Personal Ordinariates, it assigned them to the traditional, earlier dates.

Timing

The Ordo Romanus fixed the spring fast in the first week of March (then the first month), thus loosely associated with the first Sunday in Lent; the summer fast in the second week of June, after Whitsunday; the autumnal fast in the third week of September following the Exaltation of the Cross, September 14; and the winter fast in the complete week next before Christmas Eve, following St. Lucy's Day (Dec. 13).

These dates are given in the following Latin mnemonic:

Sant Crux, Lucia, Cineres, Charismata Dia

Ut sit in angariâ quarta sequens feria

Or in an old English rhyme:

Fasting days and Emberings be

Lent, Whitsun, Holyrood, and Lucie.

"Lenty, Penty, Crucy, Lucy" is a shorter mnemonic for when they fall.[9]

The ember days began on the Wednesday immediately following those days. This meant, for instance, that if September 14 were a Tuesday, the ember days would occur on September 15, 17, and 18. As a result, the ember days in September could fall after either the second or third Sunday in September. This, however, was always the liturgical Third Week of September, since the First Sunday of September was the Sunday closest to September 1 (August 29 to September 4). As a simplification of the liturgical calendar, Pope John XXIII modified this so that the Third Sunday was the third Sunday actually within the calendar month. Thus if September 14 were a Sunday, September 24, 26 and 27 would be ember days, the latest dates possible; with September 14 as a Saturday, however, the ember days would occur on September 18, 20 and 21 - the earliest possible dates.

Other regulations prevailed in different countries, until the inconveniences arising from the want of uniformity led to the rule now observed being laid down under Pope Urban II as the law of the church, at the Council of Piacenza and the Council of Clermont, 1095.

Prior to the reforms instituted after the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Catholic Church mandated fasting (only one full meal per day plus two partial, meatless meals) on all Ember Days (which meant both fasting and abstinence from meat on Ember Fridays), and the faithful were encouraged (though not required) to receive the sacrament of penance whenever possible. On February 17, 1966, Pope Paul VI's decree Paenitemini excluded the Ember Days as days of fast and abstinence for Roman Catholics.[10]

The revision of the liturgical calendar in 1969 laid down the following rules for Ember Days and Rogation days:

"In order that the Rogation Days and Ember Days may be adapted to the different regions and different needs of the faithful, the Conferences of Bishops should arrange the time and manner in which they are held. Consequently, concerning their duration, whether they are to last one or more days, or be repeated in the course of the year, norms are to be established by the competent authority, taking into consideration local needs. The Mass for each day of these celebrations should be chosen from among the Masses for Various Needs, and should be one which is more particularly appropriate to the purpose of the supplications."[11]

They may appear in some calendars as "days of prayer for peace".[12]

They were made optional by churches of the Anglican Communion in 1976. In the Episcopal Church, the September Ember Days are still (optionally) observed on the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday after Holy Cross Day,[13] so that if September 14 is a Sunday, Monday, or Tuesday, the Ember Days fall on the following Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday (in the second week of September) whereas they fall a week later (in the third week of September) for the Roman Catholic Church.

Some Lutheran church calendars continue the observation of Ember and Rogation days, though the practice has diminished over the past century.

Ordination of clergy

The rule that ordination of clergy should take place in the Ember weeks was set in documents traditionally associated with Pope Gelasius I (492–496), the pontificate of Archbishop Ecgbert of York, A.D. 732 - 766, and referred to as a canonical rule in a capitulary of Charlemagne. It was finally established as a law of the church in the pontificate of Pope Gregory VII, ca 1085.

However, why Ember Saturdays are traditionally associated with ordinations (other than episcopal ones) is unclear. By the time of at the latest Code of Canon Law (1917), major orders could also be conferred on the Saturday preceding Passion Sunday, and on the Easter Vigil; for grave reasons, on Sundays and holy days of obligation; and, for minor orders, even without grave reason, on all Sundays and double feasts (which included most saints' feasts and thus the great majority of the calendar).[14] Present Roman Catholic canon law (1983) prefers them to be conferred on Sundays and holy days of obligation, but allows them for pastoral reason on any day.[15] In practice the use of Saturdays, though not necessarily Ember Saturdays, still prevails. Subsequently, Pentecost Vigil and the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul (and Saturdays around it) have come much in use as ordination days.

Weather prediction

In the folk meteorology of the North of Spain, the weather of the ember days (témporas) is considered to predict the weather of the rest of the year. The prediction methods differ in the regions. Two frequent ones are:

- Wind-based: The season after the ember days will have as a prevailing wind the prevailing one during the ember days (some just consider the wind at midnight). That wind usually has an associated weather. Hence, if the southern wind brings dry air and clear skies, a southern wind during the winter embers forecasts a dry winter.

- Considering each day separately: The Wednesday weather predicts the weather for the first month; the Friday weather for the second month and the Saturday weather for the third month.

Other parts of the Hispanic world derive predictions from the cabañuelas days.

See also

- Rogation days

- Perchta (Quatemberca, Kvaternica, Lady of the Ember Days)

- Quarter days

- Cross-quarter day

Notes

- Mershman, Francis. "Ember Days." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 15 Sept. 2016

- More correctly a synod, convoked by King Ethelred. "Aenham" was identified as "probably Ensham, in Oxfordshire" by Thomas Lathbury, A History of the Convocation of the Church of England 1842:54. The site would have been the Abbey of Eynsham rather than the town.

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1911, s.v. "Ember Days"

- Hardon, S.J., John. "Explanation of Ember Days", Modern Catholic Dictionary, Doubleday, 1980

- Sabak, James George. The Theological Significance of "Keeping Vigil" in Rome From the Fourth to the Eighth Centuries, Catholic University of America, 2012

- Kellner, Karl Adam Heinrich. Heortology: A History of the Christian Festivals from Their Origin to the Present Day, 1908

- http://www.stjohnbaptistorthodox.org/files/calendar/2015-Western-Rite-Calendar.pdf

- 1928 Book of Common Prayer: "The Ember Days at the Four Seasons, being the Wednesday, Friday. and Saturday after the First Sunday in Lent, the Feast of Pentecost, September 14, and December 13."

- Morrow, Maria C. (2016). Sin in the Sixties. CUA Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780813228983.

- Encyclopædia Britannica article Ember days

- Universal Norms of the Liturgical Year and the Calendar, nos. 46–47 (2010 ICEL translation); for the Latin text see Normae universales de anno liturgico et de calendario

- Article Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine at Bartleby dot com

- 1979 Book of Common Prayer, p. 18: "The Ember Days, traditionally observed on the Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays after the First Sunday in Lent, the Day of Pentecost, Holy Cross Day, and December 13"

- See can. 1006, CIC 1917

- See can. 1010, CIC 1983.

![]()

External links

| Look up Ember day in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Readings and Litanies for the Ember Days

- Medieval Sourcebook: The Golden Legend: Ember Days

- William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875. Contains a description of Roman feriae.

- "Ember Days", The Old Farmer's Almanac

Weather prediction

- Peñalba, Javier (21 October 2009). "«Hace veintiséis años, tampoco yo creía en las témporas»". El Diario Vasco (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 September 2019., interview with eu:Pello Zabala, folk meteorologist.

- Garmendia Larrañaga, Juan. "meteorologia - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". Auñamendi Encyclopedia (in Basque). Eusko Ikaskuntza. Retrieved 19 September 2019.