El Cielo Biosphere Reserve

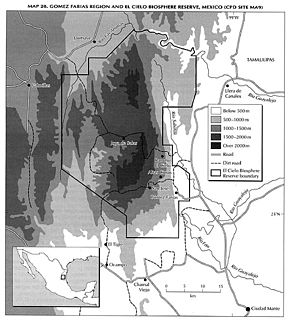

The El Cielo Biosphere Reserve (Reserva de la Biosfera El Cielo in Spanish) is located in the southern part of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas near the town of Gómez Farias. The reserve protects the northernmost extension of tropical forest and cloud forest in Mexico. It has an area of 144,530 hectares (357,100 acres; 558.0 sq mi) made up mostly of steep mountains rising from about 200 metres (660 ft) to a maximum altitude of more than 2,300 metres (7,500 ft).[1]

The state of Tamaulipas protected the area in 1985 and in 1987 it was formally recognized as a biosphere reserve by UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Programme.[2]

History

The El Cielo area attracted little attention until the 1930s. In 1935, A Canadian farmer and horticulturalist named John William Francis (Frank, Francisco, or Pancho) Harrison established a homestead he named Rancho El Cielo at 1,140 metres (3,740 ft) elevation in the cloud forest. Noted ornithologist George Miksch Sutton began fieldwork in Mexico in the late 1930s,[3] and by 1941 Sutton and Olin Sewall Pettingill Jr. embarked on a series of extended stays in the Gómez Farias region and found their way to Harrison's small ranch followed by a succession of ornithological publications.[4][5][6] Sutton's protégé, Paul S. Martin also conducted extensive fieldwork in the region from 1948 to 1953, publishing herpetological studies[7][8] that culminated with his Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico,[9] considered by some to be one of the finer examples of a biogeography in any region or discipline, "a classic treatise in historical biogeography".[10] Extensive logging and roads penetrated the area in the 1950s. In 1965, to protect the ecosystem, Harrison transferred his land to a non-profit corporation in cooperation with Texas Southmost College and the Gorgas Science Foundation. In 1966, Harrison was murdered in a land dispute with local farmers.[11]

Harrison's farm is now the El Cielo Biological Research Center (or Rancho del Cielo). In 1983, the Gorgas Science Foundation established Rancho El Cielito by purchasing land along the Sabinas River, just outside the reserve, to preserve part of a riparian ecosystem.[12]

Geography

The 144,530-hectare (357,100-acre; 558.0 sq mi) reserve has two core areas in which most human travel and exploitation are prohibited. One, 7,844 hectares (19,380 acres; 30.29 sq mi) in area, protects tropical forests while the larger core area of 28,674 hectares (70,850 acres; 110.71 sq mi) includes a cross section of the altitudes and climates of the area, especially the cloud forest. The remainder of the reserve is a buffer zone in which human activities, including limited logging, is permitted. Several communities within the reserve offer facilities for visitors and are reachable by road.[13] An ecological interpretive center is reached by paved road a few miles west of the town of Gómez Farías. The interpretive center, located at an elevation of 360 metres (1,180 ft) offers good views of the tropical forest and facilities for visitors.[14]

The reserve occupies portions of four Mexican municipalities in the state of Tamaulipas: Jaumave, Llera de Canales, Gómez Farías, and Ocampo. Within it are 26 ejidos (hamlets with communal land) and about 8,000 hectares (20,000 acres; 31 sq mi) of agricultural land used mostly to cultivate corn, beans, and rice.[15] The principal access is a road, initially paved, from the town of Gomez Farias into the interior and higher elevations. The community of Alta Cima (also known as Altas Cimas), at an elevation of 910 metres (2,990 ft) has modest lodging and restaurants for visitors. Camping is allowed.

The highest point in the reserve is 7,719 feet (2,353 m) located at 23 14N, 99 30W.[16] The lowest elevations are about 200 metres (660 ft) at the eastern, northern, and southern boundaries. The reserve is characterized by steep, north-south trending mountain ranges, eastern extensions of the Sierra Madre Oriental, made up of limestone. Typical of karst topography, caves, sinkholes, and rock outcrops are common.[17]

Flora

Several distinct vegetation types are found in the reserve. Vegetation in the drier northern and western portions of the reserve up to an elevation of 1,600 metres (5,200 ft) consists of desert and semi-desert shrublands, the montane Tamaulipan matorral and the lowland Tamaulipan mezquital. Shrubs and small trees generally do not exceed 5 metres (16 ft) in height except in riparian locations. Annual precipitation in the shrublands is less than 1,000 millimetres (39 in).[18]

In the eastern part of the reserve, sub-tropical semi-deciduous forests (Veracruz moist forests) are found at elevations of from 200 metres (660 ft) and 800 metres (2,600 ft) above sea level. The closed canopy forests averages about 20 metres (66 ft) in height. Annual precipitation of this zone is usually from 1,100 millimetres (43 in) to more than 1,800 millimetres (71 in).[19]

The principal reason for the establishment of El Cielo was the prevalence of cloud forests, distinguished by heavy precipitation, foggy conditions, and abundant mosses and fungi, at elevations of 800 metres (2,600 ft) to 1,400 metres (4,600 ft). The El Cielo cloud forests receive precipitation of about 2,500 millimetres (98 in) annually. The closed canopy forests reach a height of about 30 metres (98 ft).

Oak forests, (Sierra Madre Oriental pine-oak forests), mixed oak-pine forest, and pine forests are found at elevations of 700 metres (2,300 ft) to the top of highest summits in the reserve. These forested highland areas are drier than the cloud forests with an average precipitation of 850 millimetres (33 in) annually.[20][21]

All of the vegetation types experience a wet season from May to October and a dry season from November to April. More than 1,000 species of plants have been recorded from the cloud forests consisting of 56 percent tropical species, 20 percent temperate, 19 percent cosmopolitan, and 5 percent other. Included are species associated with the temperate climate of the eastern United States such as maple (Acer skutchii), hickory (Carya ovata), hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), and redbud (Cercis canadensis).[22]

A botanical garden and arboretum is located in Alta Cima at an elevation of 800 metres (2,600 ft).[23]

.jpg) The road into the cloud forest at El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Municipality of Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (16 April 2001)

The road into the cloud forest at El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Municipality of Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (16 April 2001) The few roads in the cloud forest of El Cielo Biosphere Reserve are suitable for four-wheel drive vehicles only (12 August 2004).

The few roads in the cloud forest of El Cielo Biosphere Reserve are suitable for four-wheel drive vehicles only (12 August 2004). Mountain streams disappear into fissures and sinkholes then reappear and disappear again throughout the karstic environment (12 August 2004).

Mountain streams disappear into fissures and sinkholes then reappear and disappear again throughout the karstic environment (12 August 2004).

Fauna

Mammals: Six species of cats, none abundant, are found in the reserve: jaguar, mountain lion, ocelot, margay, jaguarundi, and bobcat. A small population of black bears is also present. At least 255 species of birds are resident in the reserve and more than 175 migratory species have been recorded. Both birds and mammals are a mixture of temperate and tropical species.[24]

The large cats, jaguars and mountain lions, are generally regarded favorably by the people living in the reserve. Mountain lions are more often seen in the cloud forests and the higher elevations of the reserve, while jaguars are more common in the lower-elevation tropical forests.[25] Camera traps set out in tropical forests photographed eight male, female, and juvenile jaguars in a survey area of 135 square kilometres (52 sq mi). The investigators estimated a density of six jaguars per 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi). The principal prey animals of the jaguar are the lowland paca, Central American red brocket deer, white-tail deer, Virginia opossum, collared peccary, racoon, and great curassow. In addition the jaguar sometimes preys on domestic animals.[26]

Birds: The area is very rich in bird diversity, just a few of the tropical species occurring in the area include the bare-throated tiger-heron (Tigrisoma mexicanum), boat-billed heron (Cochlearius cochlearius), plumbeous kite (Ictinia plumbea), ornate hawk-eagle (Spizaetus ornatus), bat falcon (Falco rufigularis), great curassow (Crax rubra), yellow-headed parrot (Amazona oratrix), military macaw (Ara militaris), squirrel cuckoo (Piaya cayana), northern potoo (Nyctibius jamaicensis), green-breasted mango (Anthracothorax prevostii), mountain trogon (Trogon mexicanus), blue-crowned motmot (Momotus momota), pale-billed woodpecker (Campephilus guatemalensis), ivory-billed woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus flavigaster), barred antshrike (Thamnophilus doliatus), yellow-throated euphonia (Euphonia hirundinacea). [4][27]

Reptiles: Although Morelet’s crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) and several species of turtles occur in Tamaulipas, they are largely absent from the mountain slopes of El Cielo, however, the Mexican box turtle (Terrapene mexicana) has been recorded at lower elevation in the area. Paul Martin recorded 24 species of lizards and 44 snakes. Lizards include lower elevation species like the casque-headed lizard (Laemanctus serratus), Mexican spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura acanthura), and rainbow ameiva (Holcosus amphigrammus). Higher elevations support populations of banded arboreal alligator lizard (Abronia taeniata), minor spiny lizard (Sceloporus minor), Dice’s short-nosed skink (Plestiodon dicei), Madrean tropical night lizard (Lepidophyma sylvaticum), and the flathead knob-scaled lizard (Xenosaurus platyceps).[9]

The Tamaulipan montane gartersnake (Thamnophis mendax) is endemic to El Cielo. Other snake snakes include the boa constrictor (Boa [constrictor] imperator), speckled racer (Drymobius margaritiferus), mountain earth snake (Geophis latifrontalis), blunthead tree snake (Imantodes cenchoa), Mexican parrot snake (Leptophis mexicanus), brown vine snake (Oxybelis aeneus), Gaige’s pine forest snake (Rhadinaea gaigeae), tropical tree snake (Spilotes pullatus), and the terrestrial snail sucker (Tropidodipsas sartorii). Venomous snakes like the Tamaulipas rock rattlesnake (Crotalus morulus) and Totonacan rattlesnake (Crotalus totonacus) occur in the cloud forest, and the terciopelo (Bothrops asper) can be found on the lower slopes.[9]

Dice’s short-nosed skink (Plestiodon dicei), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (12 August 2004).

Dice’s short-nosed skink (Plestiodon dicei), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (12 August 2004). Flathead knob-scaled lizard(Xenosaurus platyceps), Municipality of Victoria, Tamaulipas (12 July 2004)

Flathead knob-scaled lizard(Xenosaurus platyceps), Municipality of Victoria, Tamaulipas (12 July 2004) Northern speckled racer (Drymobius margaritiferus), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Mexico (12 August 2004).

Northern speckled racer (Drymobius margaritiferus), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Mexico (12 August 2004). Tamaulipan Rock Rattlesnake (Crotalus morulus), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (27 May 2005).

Tamaulipan Rock Rattlesnake (Crotalus morulus), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (27 May 2005). Central American boa constrictor (Boa imperator), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (23 August 2007).

Central American boa constrictor (Boa imperator), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (23 August 2007).

Amphibians: Two endemic salamanders are known from, the El Cielo salamander (Chiropterotriton cieloensis) and graceful flat-footed salamander (Chiropterotriton cracens). Other species include the Tamaulipan false brook salamander (Aquiloeurycea scandens), broadfoot mushroomtongue salamander (Bolitoglossa platydactyla)[28] and Bell’s salamander (Isthmura bellii). Frogs and toads from the region include the Rio Grande leopard frog (Lithobates berlandieri), Mexican treefrog (Smilisca baudinii), small-eared treefrog (Rheohyla miotympanum), mountain treefrog (Dryophytes eximius), long-footed chirping frog (Eleutherodactylus longipes), and predominantly subterranean species like the barking frog (Craugastor augusti) and Adorned Robber frog (Craugastor decoratus). At lower elevations the sabinal frog (Leptodactylus melanonotus), veined treefrog (Trachycephalus [vermiculatus] typhonius, sheep frog (Hypopachus variolosus), and the burrowing toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis) may be found.[9]

Chunky false brook salamander (Aquiloeurycea cephalica), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (12 August 2004).

Chunky false brook salamander (Aquiloeurycea cephalica), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (12 August 2004). Tamaulipan false brook salamander (Aquiloeurycea scandens), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (25 May 2005).

Tamaulipan false brook salamander (Aquiloeurycea scandens), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (25 May 2005). Bell’s salamander (Isthmura bellii), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (27 September 2004).

Bell’s salamander (Isthmura bellii), El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Tamaulipas, Mexico (27 September 2004). Mexican treefrog (Smilisca baudinii), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (8 August 2004).

Mexican treefrog (Smilisca baudinii), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (8 August 2004). Veined treefrog (Trachycephalus typhonius), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (5 June 2002).

Veined treefrog (Trachycephalus typhonius), Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, Mexico (5 June 2002).

Fishes: Although the steep mountain slopes and karstic environment do not support a large fish diversity, lower elevation tributaries in the Rio Guayalejo drainage, such as the Rio Sabinas and Rio Frio and associated springs and creeks contain species like the longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus), red shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis), lantern minnow (Dionda ipni), pigmy shiner (Notropis tropicus), Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus), gold gambusia (Gambusia aurata), Forlón gambusia (Gambusia regani), Gulf gambusia (Gambusia vittata), mountain swordtail (Xiphophorus nezahualcoyotl), and variable platyfish (Xiphophorus variatus), Tamesí molly (Poecilia latipunctata), and the Amazon molly (Poecilia formosa), an all female species, reproduces through gynogenesis. The phantom blindcat (Prietella lundbergi) is known only from subterranean waters and has been collected by cave drivers at depths of 50 meters in Rio Frio cave systems.[29][30]

Climate

The climate of Gómez Farías, to the east, is typical of the lower and wetter elevations of the reserve. Higher elevations are substantially cooler and precipitation declines rapidly on the western slopes of the mountains. The Sierra Madre Oriental create a rain shadow effect. The town of Jaumave, Tamaulipas at the northwestern entrance to the reserve receives only 17.9 inches (450 mm) of precipitation annually and has a semi-arid, near-desert climate. Freezing temperatures are rare at the lower elevations of El Cielo, but common in winter at elevations of more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)

| Climate data for Gomez Farias, Tamaulipas. 23 03 N, 99 09W. Elevation: 327 metres (1,073 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.3 (90.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.3 (63.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31 (1.2) |

30 (1.2) |

47 (1.9) |

77 (3.0) |

172 (6.8) |

323 (12.7) |

365 (14.4) |

270 (10.6) |

289 (11.4) |

153 (6.0) |

50 (2.0) |

39 (1.5) |

1,847 (72.7) |

| Source: Weatherbase: Gomez Farias, Tamaulipas.[31] | |||||||||||||

References

- Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/libros/2/cielo.html, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- "Gomez Farias Region and El Cielo Biosphere Reserve", http://www.botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/ma/ma9.htm Archived 2015-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Sutton, George Miksch and Thomas D. Burleigh. (1939). A list of birds observed on the 1938 Semple Expedition to northeastern Mexico. Louisiana State University Museum of Zoology, Occasional Paper No. 3: 1-46.

- Sutton, George Miksch and Olin Sewall Pettingill Jr. (1942). Birds of the Gomez Farias Region, Southwestern Tamaulipas. The Auk, 59(1): 1-34.

- Sutton, George Miksch. (1951). Mexican Birds: First Impressions Based Upon an Ornithological Expedition to Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, and Coahuila with an Appendix Briefly Describing all Mexican Birds. University of Oklahoma Press

- Sutton, G. M. 1972. At a Bend in a Mexican River. Paul S. Eriksson, Inc. Publisher, New York, New York xvii, 184. ISBN 0-8397-0780-0

- Martin, Paul S. (1955). Zonal Distribution of Vertebrates in a Mexican Cloud Forest. American Naturalist 89: 347-361.

- Martin, Paul S. (1955). Herpetological Records from the Gómez Farias Region of Southwestern Tamaulipas, Mexico. Copeia 1955(3): 173-180.

- Martin, Paul S. 1958. A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology University of Michigan, 101: 1-102.

- Adler, Kraig. (2012). Contributions to the History of Herpetology, Vol. III. Contributions to Herpetology Vol. 29. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 564 pp. ISBN 978-0-916984-82-3

- Webster, Fred and Marie S. The Road to El Cielo, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001, pp. 113-118; "Gomez Farias Region and El Cielo Biosphere Reserve", http://www.botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/ma/ma9.htm Archived 2015-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- "Rancho El Cielo and Rancho El Cielito", Gorgas Science Foundation http://www.gsfinc.org/focus/mexico Archived 2014-12-25 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 23 Dec 2014

- Sosa Florescano, Alejandra, "El Cielo: A Reserve Teeming with Life" http://www.revistascisan.unam.mx/Voices/pdfs/6822.pdf, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Google Earth

- Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/libros/2/cielo.html, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Google Earth

- "Gomez Farias Region and El Cielo Biosphere Reserve", http://www.botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/ma/ma9.htm Archived 2015-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- "Tamaulipan Matorral" http://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na1311, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- "Veracruz Moist Forests" http://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0176, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/libros/2/cielo.html, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Downey, Patricia J.; Hellgren, Eric C.; Caso, Arturo; Carvajal, Sasha; Frangioso, Kerri (2007). "Hair Snares for Noninvasive Sampling of Felids in North America: Do Gray Foxes Affect Success?". Journal of Wildlife Management. 71 (6): 2090–2094. doi:10.2193/2006-500.

- "Gomez Farias Region and El Cielo Biosphere Reserve", http://www.botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/ma/ma9.htm Archived 2015-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- "Botanical Gardens Conservation International" http://www.bgci.org/garden.php?id=3594&ftrCountry=MX&ftrKeyword=&ftrBGCImem=&ftrIAReg=, accessed 22 Dec 2014

- Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/libros/2/cielo.html, accessed 18 Dec 2014

- Tiefenbacher, John; Teinert, Brian P. "Attitudes toward Jaguars and Pumas in the El Cielo Biosphere Reserve, Mexico". Academia. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Carrera-Trevino, Rogelio; Lira-Torres, Ivan; Martinez-Garcia, Luis; Lopez-Hernandez, Martha. "El Jaguar en la Reserva de la biosfera 'El Cielo,' Tamaulipas, Mexico". Academia. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Howell, S. N. G. and S. Webb. (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Cantral America. Oxford University Press. Oxford. xvi, 851 pp. ISBN 0-19-854012-4

- Farr, William L., Pablo A. Lavin-Murcio, and David Lazcano. (2007). New Distributional Records for Amphibians and Reptiles from the State of Tamaulipas, Mexico. Herpetological Review 38(2): 226-233.

- Miller, R. R., W. L. Minckley, and S. M. Norris. (2005). Freshwater Fishes of Mexico. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. xxv, 490 pp. ISBN 0-226-52604-6

- García de León, Francisco J., Delladira Gutiérrez Tirado, Dean A. Hendrickson, and Héctor Espinosa Pérez (2005). Fishes of the Continental Waters of Tamaulipas: Diversity and Conservation Status. In Jean-Luc E. Cartron, Gerardo Ceballos, and Richard S. Felger (eds.). Biodiversity, Ecosystems, and Conservation in Northern Mexico. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, N. Y. xvi, 496 pp. ISBN 0-19-515672-2

- http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=928136&cityname=G%F3mez-Far%EDas-Tamaulipas-Mexico&units=metric , accessed 18 December 2014