Amarna

Amarna (/əˈmɑːrnə/; Arabic: العمارنة, romanized: al-ʿamārnah) is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site that represents the remains of the capital city newly established (1346 BC) and built by the Pharaoh Akhenaten of the late Eighteenth Dynasty, and abandoned shortly after his death (1332 BC).[1] The name for the city employed by the ancient Egyptians is written as Akhetaten (or Akhetaton—transliterations vary) in English transliteration. Akhetaten means "Horizon of the Aten".[2]

العمارنة | |

Small Temple of the Aten at Akhetaten | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Alternative name | El-Amarna, Tell el-Amarna |

|---|---|

| Location | Minya Governorate, Egypt |

| Region | Upper Egypt |

| Coordinates | 27°38′43″N 30°53′47″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Akhenaten |

| Founded | Approximately 1346 BC |

| Periods | Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, Roman Empire |

The area is located on the east bank of the Nile River in the modern Egyptian province of Minya, some 58 km (36 mi) south of the city of al-Minya, 312 km (194 mi) south of the Egyptian capital Cairo and 402 km (250 mi) north of Luxor.[3] The city of Deir Mawas lies directly west across from the site of Amarna. Amarna, on the east side, includes several modern villages, chief of which are el-Till in the north and el-Hagg Qandil in the south.

The region flourished from the Amarna period up to the later Roman era.[4]

Name

The name Amarna comes from the Beni Amran tribe that lived in the region and founded a few settlements. The ancient Egyptian name was Akhetaten.

(This site should be distinguished from Tell Amarna in Syria, a Halaf period archaeological tell.[5])

English Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson visited Amarna twice in the 1820s and identified it as Alabastron,[6] following the sometimes contradictory descriptions of Roman-era authors Pliny (On Stones) and Ptolemy (Geography),[7][8] although he was not sure about the identification and suggested Kom el-Ahmar as an alternative location.[9]

City of Akhetaten

The area of the city was effectively a virgin site, and it was in this city that the Akhetaten described as the Aten's "seat of the First Occasion, which he had made for himself that he might rest in it".

It may be that the Royal Wadi's resemblance to the hieroglyph for horizon showed that this was the place to found the city.

The city was built as the new capital of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, dedicated to his new religion of worship to the Aten. Construction started in or around Year 5 of his reign (1346 BC) and was probably completed by Year 9 (1341 BC), although it became the capital city two years earlier. To speed up construction of the city most of the buildings were constructed out of mud-brick, and white washed. The most important buildings were faced with local stone.[10]

It is the only ancient Egyptian city which preserves great details of its internal plan, in large part because the city was abandoned after the death of Akhenaten, when Akhenaten's son, King Tutankhamun, decided to leave the city and return to his birthplace in Thebes (modern Luxor). The city seems to have remained active for a decade or so after his death, and a shrine to Horemheb indicates that it was at least partially occupied at the beginning of his reign,[11] if only as a source for building material elsewhere. Once it was abandoned it remained uninhabited until Roman settlement[4] began along the edge of the Nile. However, due to the unique circumstances of its creation and abandonment, it is questionable how representative of ancient Egyptian cities it actually is. Amarna was hastily constructed and covered an area of approximately 8 miles (13 km) of territory on the east bank of the Nile River; on the west bank, land was set aside to provide crops for the city's population.[2] The entire city was encircled with a total of 14 boundary stelae detailing Akhenaten's conditions for the establishment of this new capital city of Egypt.[2]

The earliest dated stele from Akhenaten's new city is known to be Boundary stele K which is dated to Year 5, IV Peret (or month 8), day 13 of Akhenaten's reign.[12] (Most of the original 14 boundary stelae have been badly eroded.) It preserves an account of Akhenaten's foundation of this city. The document records the pharaoh's wish to have several temples of the Aten to be erected here, for several royal tombs to be created in the eastern hills of Amarna for himself, his chief wife Nefertiti and his eldest daughter Meritaten as well as his explicit command that when he was dead, he would be brought back to Amarna for burial.[13] Boundary stela K introduces a description of the events that were being celebrated at Amarna:

His Majesty mounted a great chariot of electrum, like the Aten when He rises on the horizon and fills the land with His love, and took a goodly road to Akhetaten, the place of origin, which [the Aten] had created for Himself that he might be happy therein. It was His son Wa'enrē [i.e. Akhenaten] who founded it for Him as His monument when His Father commanded him to make it. Heaven was joyful, the earth was glad every heart was filled with delight when they beheld him.[14]

This text then goes on to state that Akhenaten made a great oblation to the god Aten "and this is the theme [of the occasion] which is illustrated in the lunettes of the stelae where he stands with his queen and eldest daughter before an altar heaped with offerings under the Aten, while it shines upon him rejuvenating his body with its rays."[14]

Site and plan

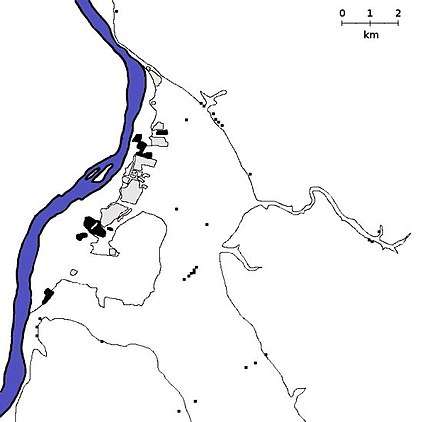

Located on the east bank of the Nile, the ruins of the city are laid out roughly north to south along a "Royal Road", now referred to as "Sikhet es-Sultan".[15][16] The Royal residences are generally to the north, in what is known as the North City, with a central administration and religious area and the south of the city is made up of residential suburbs.

North City

If one approached the city of Amarna from the north by river the first buildings past the northern boundary stele would be the North Riverside Palace. This building ran all the way up to the waterfront and was likely the main residence of the Royal Family.[17] Located within the North City area is the Northern Palace, the main residence of the Royal Family. Between this and the central city, the Northern Suburb was initially a prosperous area with large houses, but the house size decreased and became poorer the further from the road they were.[16]

Central City

Most of the important ceremonial and administrative buildings were located in the central city. Here the Great Temple of the Aten and the Small Aten Temple were used for religious functions and between these the Great Royal Palace and Royal Residence were the ceremonial residence of the King and Royal Family, and were linked by a bridge or ramp.[18] Located behind the Royal Residence was the Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh, where the Amarna Letters were found.[19]

This area was probably the first area to be completed, and had at least two phases of construction.[15]

Southern suburbs

To the south of the city was the area now referred to as the Southern Suburbs. It contained the estates of many of the city's powerful nobles, including Nakhtpaaten (Chief Minister), Ranefer, Panehesy (High Priest of the Aten) and Ramose (Master of Horses). This area also held the studio of the sculptor Thutmose, where the famous bust of Nefertiti was found in 1912.[20]

Further to the south of the city was Kom el-Nana, an enclosure, usually referred to as a sun-shade, and was probably built as a sun-temple.,[21] and then the Maru-Aten, which was a palace or sun-temple originally thought to have been constructed for Akhenaten's queen Kiya, but on her death her name and images were altered to those of Meritaten, his daughter.[22]

City outskirts

- See also Workmen's Village, Amarna

Surrounding the city and marking its extent, the Boundary Stelae (each a rectangle of carved rock on the cliffs on both sides of the Nile) describing the founding of the city are a primary source of information about it.[23]

Away from the city Akhenaten's Royal necropolis was started in a narrow valley to the east of the city, hidden in the cliffs. Only one tomb was completed, and was used by an unnamed Royal Wife, and Akhenaten's tomb was hastily used to hold him and likely Meketaten, his second daughter.[24]

In the cliffs to the north and south of the Royal Wadi, the nobles of the city constructed their Tombs.

Life in ancient Amarna/Akhetaten

Much of what is known about Amarna's founding is due to the preservation of a series of official boundary stelae (13 are known) ringing the perimeter of the city. These are cut into the cliffs on both sides of the Nile (10 on the east, 3 on the west) and record the events of Akhetaten (Amarna) from founding to just before its fall.[25]

To make the move from Thebes to Amarna, Akhenaten needed the support of the military. Ay, one of Akhenaten's principal advisors, exercised great influence in this area because his father Yuya had been an important military leader. Additionally, everyone in the military had grown up together, they had been a part of the richest and most successful period in Egypt's history under Akhenaten's father, so loyalty among the ranks was strong and unwavering. Perhaps most importantly, "it was a military whose massed ranks the king took every opportunity to celebrate in temple reliefs, first at Thebes and later at Amarna."[26]

Religious life

While the reforms of Akhenaten are generally believed to have been oriented towards a sort of monotheism, or perhaps more accurately, monolatrism. Archaeological evidence shows other deities were also revered, even at the centre of the Aten cult – if not officially, then at least by the people who lived and worked there.

... at Akhetaten itself, recent excavation by Kemp (2008: 41–46) has shown the presence of objects that depict gods, goddesses and symbols that belong to the traditional field of personal belief. So many examples of Bes, the grotesque dwarf figure who warded off evil spirits, have been found, as well as of the goddess-monster, Taweret, part crocodile, part hippopotamus, who was associated with childbirth. Also in the royal workmen’s village at Akhetaten, stelae dedicated to Isis and Shed have been discovered (Watterson 1984: 158 & 208).[27]

Amarna art-style

The Amarna art-style broke with long-established Egyptian conventions. Unlike the strict idealistic formalism of previous Egyptian art, it depicted its subjects more realistically. These included informal scenes, such as intimate portrayals of affection within the royal family or playing with their children, and no longer portrayed women as lighter coloured than men. The art also had a realism that sometimes borders on caricature.

While the worship of Aten was later referred to as the Amarna heresy and suppressed, this art had a more lasting legacy.

Rediscovery and excavation

18th and 19th century excavations

The first western mention of the city was made in 1714 by Claude Sicard, a French Jesuit priest who was travelling through the Nile Valley, and described the boundary stela from Amarna. As with much of Egypt, it was visited by Napoleon's corps de savants in 1798–1799, who prepared the first detailed map of Amarna, which was subsequently published in Description de l'Égypte between 1821 and 1830.[28]

After this European exploration continued in 1824 when Sir John Gardiner Wilkinson explored and mapped the city remains. The copyist Robert Hay and his surveyor G. Laver visited the locality and uncovered several of the Southern Tombs from sand drifts, recording the reliefs in 1833. The copies made by Hay and Laver languish largely unpublished in the British Library, where an ongoing project to identify their locations is underway.[29]

The Prussian expedition led by Richard Lepsius visited the site in 1843 and 1845, and recorded the visible monuments and topography of Amarna in two separate visits over a total of twelve days, using drawings and paper squeezes. The results were ultimately published in Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien between 1849 and 1913, including an improved map of the city.[28] Despite being somewhat limited in accuracy, the engraved Denkmäler plates formed the basis for scholastic knowledge and interpretation of many of the scenes and inscriptions in the private tombs and some of the Boundary Stelae for the rest of the century. The records made by these early explorers teams are of immense importance since many of these remains were later destroyed or otherwise lost.

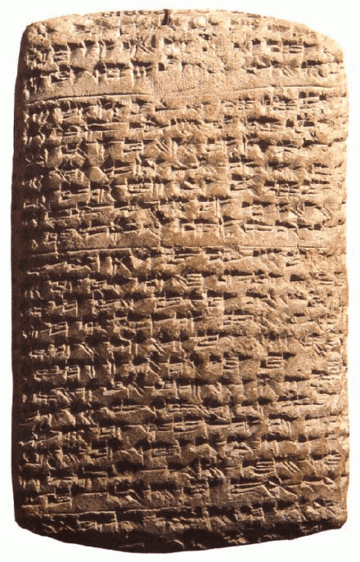

The Amarna letters

In 1887 a local woman digging for sebakh uncovered a cache of over 300 cuneiform tablets (now commonly known as the Amarna Letters).[30] These tablets recorded select diplomatic correspondence of the Pharaoh and were predominantly written in Akkadian, the lingua franca commonly used during the Late Bronze Age of the Ancient Near East for such communication. This discovery led to the recognition of the importance of the site, and lead to a further increase in exploration.[31]

Excavation of the king's tomb

Between 1891 and 1892 Alessandro Barsanti 'discovered' and cleared the king's tomb (although it was probably known to the local population from about 1880).[32] Around the same time Sir Flinders Petrie worked for one season at Amarna, working independently of the Egypt Exploration Fund. He excavated primarily in the Central City, investigating the Great Temple of the Aten, the Great Official Palace, the King's House, the Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh and several private houses. Although frequently amounting to little more than a sondage (survey), Petrie's excavations revealed additional cuneiform tablets, the remains of several glass factories, and a great quantity of discarded faience, glass and ceramic in sifting the palace rubbish heaps (including Mycenaean sherds).[31] By publishing his results and reconstructions rapidly, Petrie was able to stimulate further interest in the site's potential.

20th century excavations

The copyist and artist Norman de Garis Davies published drawn and photographic descriptions of private tombs and boundary stelae from Amarna from 1903 to 1908. These books were republished by the EES in 2006.

In the early years of the 20th century (1907 to 1914) the Deutsche Orientgesellschaft expedition, led by Ludwig Borchardt, excavated extensively throughout the North and South suburbs of the city. The famous bust of Nefertiti, now in Berlin's Ägyptisches Museum, was discovered amongst other sculptural artefacts in the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose. The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 terminated the German excavations.

From 1921 to 1936 an Egypt Exploration Society expedition returned to excavation at Amarna under the direction of T.E. Peet, Sir Leonard Woolley, Henri Frankfort, Stephen Glanville[33] and John Pendlebury. Mary Chubb served as the digs administrator. The renewed investigations were focused on religious and royal structures.

During the 1960s the Egyptian Antiquities Organization (now the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities) undertook a number of excavations at Amarna.

21st century excavations

Exploration of the city continues to the present, currently under the direction of Barry Kemp (Emeritus Professor in Egyptology, University of Cambridge, England) (until 2006, under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Society and now with the "Amarna Project".).[11][34] In 1980 a separate expedition led by Geoffrey Martin described and copied the reliefs from the Royal Tomb, later publishing its findings together with objects thought to have come from the tomb. This work was published in 2 volumes by the EES.

From 2005 to 2013, the Amarna Project excavated at a cemetery of private individuals, close to the southern tombs of the Nobles.[35]

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

- List of historical capitals of Egypt

Notes

- "The Official Website of the Amarna Project". Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- David (1998), p. 125

- "Google Maps Satellite image". Google. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- "Middle Egypt Survey Project 2006". Amarna Project. 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- "Tell Amarna in the general framework of the Halaf period". academia.edu. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Digital Egypt for Universities: Amarna". University College London. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1828). Materia hieroglyphica. Malta: privately printed. p. 22. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Alfred Lucas & John Richard Harris (2011). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (reprint of 4th edition (1962), revised from first (1926) ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-486-40446-2. Retrieved 26 July 2016.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Modern Egypt and Thebes: being a description of Egypt; including the information required for travellers in that country. II. London: John Murray. 1843. pp. 43–44. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Grundon (2007), p. 89

- "Excavating Amarna". Archaeology.org. 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- Aldred (1988), p .47

- Aldred (1988), pp. 47–50

- Aldred (1988), p. 48

- Waterson (1999), p. 81

- Grundon (2007), p. 92

- Kemp, Barry, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People, Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 151–153

- Waterson (1999), p. 82

- Moran (1992), p. xiv

- Waterson (1999), p. 138

- "Kom El-Nana". Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- Eyma (2003), p. 53

- "Boundary Stelae". Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Royal Tomb". Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- Silverman, David P; Wegner, Josef W; Jennifer Houser (2006). Akhenaten and Tutankhamun, Revolution and Restoration. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania.

- Reeves, Nicholas (2001). Akhenaten, Egypt's False Prophet. London, UK: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Turner, Philip (2012). Seth – a misrepresented god in the Ancient Egyptian pantheon? (PhD). Manchester, UK: University of Manchester.

- "Mapping Amarna". Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- "The Robert Hay Drawings in the British Library". Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Wallis Budge describes the discovery of the Amarna tablets". Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Grundon (2007), pp. 90–91

- "Royal Tomb". The Amarna Project. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Grundon(2007), p. 71

- "Fieldwork – Tell El-Armana". Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- John Hayes-Fisher (2008-01-25). "Grim secrets of Pharaoh's city". BBC Timewatch. news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

References

- Aldred, Cyril (1988). Akhenaten: King of Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05048-4. OCLC 17997212.

- David, Rosalie (1998). Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt. Facts on File.

- de Garis Davies, Norman (1903–1908). The Rock Tombs of El Amarna. Parts 1–6. London: EES.

- Eyma, Aayko, ed. (2003). A Delta-Man in Yebu. Universal-Publishers.

- Grundon, Imogen (2007). The Rash Adventurer, A Life of John Pendlebury. London: Libri.

- Hess, Richard S. (1996). Amarna Personal Names (Thesis). Winona Lake, IN: American Schools of Oriental Research. DASOR, 9.

- Kemp, Barry (2012). The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Amarna and its People. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- Martin, G.T. (1989) [1974]. The Royal Tomb at el-'Amarna. London, UK: EES. 2 vols.

- Moran, William L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4251-4.

- Redford, Donald (1984). Akhenaten: The Heretic King. Princeto, NJ.

- Waterson, Barbara (1999). Amarna: Ancient Egypt's Age of Revolution.

Further reading

- Freed, Rita A., Yvonne J. Markowitz, and Sue H. D’Auria, eds. 1999. Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Giles, Frederick John. 2001. The Amarna Age: Egypt. Warminster, Wiltshire, England: Aris & Phillips.

- Kemp, Barry J. 2006. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. 2d ed. London: Routledge.

- Kemp, Barry J. 2012. The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Murnane, William J. 1995. Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt. Atlanta: Scholars.

- Mynářová, Jana. 2007. Language of Amarna – Language of Diplomacy: Perspectives On the Amarna Letters. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology; Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague.

- Watterson, Barbara. 1999. Amarna: Ancient Egypt's Age of Revolution. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Amarna. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amarna. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Amarna. |

| Library resources about Amarna |

- "Amarna Project". The University of Cambridge.

- "Amarna Art Gallery". — Shows just a few, but stunning, examples of the art of the Amarna period.

- "M.A. Mansoor Amarna Collection".

- "The Amarna3D Project". — 3D visualisation of the city developed by Paul Docherty.

| Preceded by Thebes |

Capital of Egypt (Akhetaten) c. 1353 BC – c. 1332 BC |

Succeeded by Thebes |