South Tombs Cemetery, Amarna

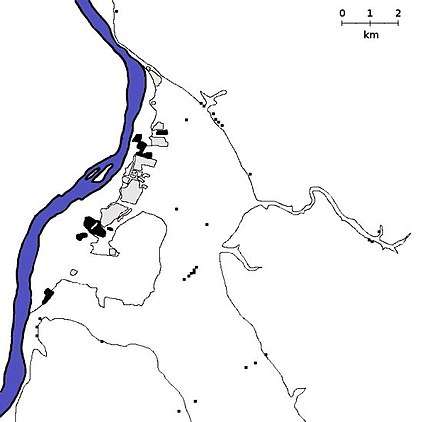

The South Tombs Cemetery is an Ancient Egyptian necropolis in Amarna, Upper Egypt. It is the burial place of low status individuals from the ancient city of Akhetaten. The site is located close to the Southern Tombs of the Nobles.[1] Archaeological excavation was undertaken by the Egypt Exploration Society between 2006 and 2013.

Discovery

This cemetery was discovered in 2003 during GPS surveying of the desert by the Egypt Exploration Society.[2] It is situated on the east side of a narrow wadi that runs southward and to the east behind Southern Tomb 25 (Ay). It appears to have been thoroughly robbed and partially washed away by floods, leaving a scatter of human bone on the floor of the valley and across the plain.[3] It was the subject of a systematic survey in 2005.[3] Excavation commenced in 2006[4] and concluded in 2013.[5]

Investigation

2005 survey

Analysis of the skeletal material collected during the 2005 survey represented 53 adults, of which 19 were identified as female and 18 as male, 14 juveniles between the ages of 5 and 17, and three infants. Low levels of arthritis, joint degeneration, and trauma indicate that work loads were not excessive. There appear to be high levels of childhood anemia indicating diet and iron deficiencies.[3]

2006 excavation

The cemetery was robbed extensively in the past. A pile of five torsos was excavated where the robbers had likely dumped them after pulling them from their graves. Evidence of fabric and matting coverings was found, along with woven wooden coffins, one solid wooden coffin, and one brick vaulted tomb which contained fragments of another wooden coffin.There were no signs of artificial mummification.[6]

Skeletal material representing at least 27 individuals was recovered. There were 16 adults with 13 being aged between 20 and 35, two aged 35–50, and one of unknown age. 10 juveniles were recovered: four were aged between five and 10 years; two were 10-15; four were aged 15–20 years. One infant (0-five years) was recovered. Of the aged skeletons, 15 were male or possible males. This sexing was done exclusively using skulls due to the disturbed nature of the burials. The virtual absence of babies and the high proportion of young adults is the inverse of the expected mortality ratios; this suggests that the population lived under high stress and suffered from high mortality rates. The spines of seven individuals were examined and over half were found to have suffered trauma such as fractures and Schmorl's nodes as a result of carrying heavy loads at an early age. 36% of the individuals displayed symptoms of anemia characterised by cribra orbitalia.[7]

79 artefacts were recovered consisting of beads and pendants, including two scarabs, one of which was inscribed for Menkheperre (Thutmose III). The stand-out find of the season consisted of two rectangular limestone stelae. One had a triangular top, and the other had three triangular projections on the top edge. Both stelae feature carefully cut recesses that would have held plaques of another material like wood, faience, or metal held in place with gypsum cement, of which no trace remains due to weathering.[8]

2007 excavation

A minimum of 29 individuals were identified from in situ burials and a total of 33 skulls were recovered. No evidence of mummification was found. The majority of the bodies were wrapped in textiles: two were wrapped in linen strips, while open-work matting made from tamarisk stems was common as an outer wrapping some burials also had a second inner layer of matting made from a variety of plant materials such as bark, date palm husks, or reeds. Fragments of wood and decorated gypsum plaster indicate at least one individual was interred in a coffin; wood fragments from a disturbed burial indicate there were likely others buried in coffins. The number of infants continued to be lower than expected and the majority of individuals were juveniles or adults.[9]

2008 excavation

Burials continue to be those of juveniles, young adults, and adults, with infants in the minority. Six graves excavated in this season contained the body of more than one person. A grand total of 76 individuals had been excavated across the three seasons. Again no evidence of mummification was present. Bodies were commonly wrapped in textiles and then matting. One individual was buried in a rectangular wooden coffin, an infant was buried in a bark or wood coffin, and a woman was buried in an elaborate anthropoid coffin. The coffin was made of sycamore fig, tamarisk, and Mimusops sp. wood; with the exception of the face, the whole is badly eaten by termites. Painted fragments of the decoration name the deceased as Maiay. Horizontal bands give short prayers known from the period and she asks to receive offerings. The side panels preserve mourning figures. There is no sign of the Aten or royal family.

Artefact finds included some faience beads, a scarab, a cowrie-shaped bead, a kohl tube and stick, a fragmentary gypsum window grille, a fragmentary triangle-topped stela, a fragmentary offering table, a model oar, and an adze placed alongside the face of an individual between inner and outer shroud layers.[10]

2009 excavation

In this season the excavation was spread over two separated areas designated the 'upper' and 'lower' sites.

Lower site: The remains of 29 individuals were recovered. 15 were adults - seven women and eight men. 10 were subadults of which seven are infants (0-5). The population demographic in this area is in keeping what is expected for ancient populations. Bodies continue to be wrapped in textile and then matting. Graves in this area are noted as being less crowded. There were no definite double burials of adults; where they occurred they were an adult interred with an infant or subadult. Compared to the upper site, this area had a higher proportion of wooden coffins and stelae, together with a small pyramidion. Graves were often marked with cairns of stone. The graves continue to contain few grave goods and suffer extensively from ancient robbing. This area is located closer to the tombs of the officials at the mouth of the wadi, which may suggest a slightly higher status; however, the those buried here still suffered the effects of poor nutrition and lived hard-working lives. One of the stelae recovered in this season retained traces of incised decoration depicting the deceased seated in front of an offering table wearing a large wig topped with a perfume cone. These stelae continued to be rectangular with pointed or double pointed tops with a central recess.[11]

Upper site: 35 individuals were recovered from 29 burials. Infant and juvenile burials dominate. The mode of burial is the same as in the lower site, consisting of textile wrapping and matting coffins. No wooden coffins were found. Seven of the graves excavated contained multiple bodies; these range from an adult buried with a foetus to the burial of two adults and two children. The concentration of graves on the terrace of the wadi has led to crowding. The grave cuts have not encroached on each other indicating that there was a successful mode of differentiating the plots, although this method has not survived. Grave goods continue to be sparse, with most burials containing at least one pottery vessel, and some finds of beads or amulets. One grave contained a copper-bronze mirror wrapped in fine cloth, a kohl stick, and a possible wig.[12]

2010 excavation

In this season a new excavation area was opened at the mouth of the wadi in order to determine how far the cemetery extended and how it interacted with the nearby rock tombs.

Wadi mouth site: This area is characterised by gently sloping ground with shallow interments due to the underlying bedrock. 17 individuals were recovered from 17 burials. One grave was entirely robbed and one contained a double infant burial. The vast majority of burials continued to be those of young adults and children. This excavation encountered a smaller number of disturbed burials, perhaps due to the more visible location at the mouth of the valley. The treatment of the body is consistent with what has been found previously. Burial goods continue to be extremely rare. Some graves were covered with cairns of stone.[13]

Lower site: 33 graves were exposed but only 30 were excavated. 30 individuals were recovered with only two double burials - an adult and child, and a child and an infant. Three wooden coffins were found. Two burials were in painted anthropoid wooden coffins which had been completely robbed out. Both coffins depict figures bearing offerings; the inscriptions of one appear to be unintelligible while the second bears the names Hesy(t)en-Ra and Hesy(t)en-Aten. The treatment of bodies is consistent with what has been found previously. Grave goods are not common; limited to pottery vessels and jewellery. Interestingly, single amulets, often scarabs, were placed in or worn on the left hand including one inscribed for Nebmaatre (Amenhotep III). This excavation season gave the first example of clear cairn-grave association. Two stone stelae were recovered. The best preserved example is round-topped depicting a man and woman seated and embracing before a male figure who gives offerings.[14]

Upper site: The excavation of 22 graves yielded the remains of 28 individuals. Some of the graves were empty while others held two or three bodies. Adults, young adults, and children dominate. No signs of artificial mummification were found. The bodies continue to be wrapped in shrouds, and often a separate layer of matting. Only two wooden coffins were found- one for a child, and one very large one that would have contained more than one adult. The inclusion of pottery was common, some vessels contained fruit and grains. Some jewellery in the form of beads and amulets is present. The most unusual finds of the excavation were a 'double scarab' bead of steatite and three beads in the shape of a hippopotamus with Taweret on the underside of the larger bead, and Bes, and a seated goddess on the other. One of two of the only extant 'incense cones' was found on head of an adult woman.[15] One funerary stela incised with the deceased seated at an offering table was recovered.[16]

The persistent high proportion of burials of individuals aged between 10 and 20 represents a "catastrophic burial assemblage" as these are the ages when deaths should be fewest. Malnutrition in childhood resulted in small stature and a failure to grow properly. The presence of frequent healed fractures of the hands, arms, legs, feet, and vertebrae indicate accidents were common and so was the carrying heavy loads.[17]

2011 excavation

No excavation was undertaken at the "upper site" this year.

Wadi mouth site: The remains of 14 individuals were recovered this season. The individuals represented ranged from a foetus to a 50 year old adult. Two wooden coffins were encountered; one wooden coffin for an infant and a painted coffin for an child. This coffin was not excavated this season.[18]

Lower site: 29 individuals were recovered during the excavation of this area. The individuals represented included babies, children, and adults. Three wooden coffins were found: two wooden coffins for infants and one wooden anthropoid coffin. The decoration of the coffin depicted the Four Sons of Horus. The remains of four individuals were recovered from within the coffin but the original occupant was likely a young woman; the remains of a second trimester foetus were found within her pelvis.[18]

Bodies continue to be wrapped in textiles or matting. Grave goods continue to be rare. Significant finds this season included a hollow clay ball placed beside the head of an infant, a toe ring, a ring bearing an image of Ra-Horakhty, and two pieces of gold sheeting. Some burials had been covered by stone cairns. No trace of stelae or pyramidia were found but the grave layouts were orderly. Analysis of the bones found a high instance of spinal and limb fractures, along with osteoarthritis, infections, and poor diet in childhood.[19]

2012 and 2013 excavation

The aim of these seasons was to reach 400 excavated individuals. The aim of the 2012 season was to balance the number of individuals from the excavated areas. To this end, more excavation was undertaken at the wadi mouth site and the lower site. Work at the upper site was limited to clearing graves left unexcavated in the 2010 season. The aim of the 2013 season was reach the 400 individual target. Work was extended at the upper site due to the higher frequency of multiple burials. A new area, the "middle site", was opened to investigate the previously unexplored middle of the cemetery. Some excavation was carried out to determine the edges of the cemetery and if they corresponded to the surface scatters.[20]

Wadi mouth site: 47 individuals were recovered from 49 graves. Three painted wooden coffins were excavated. The child's coffin encountered in the 2011 season was lifted. It was found that a hole had been cut in the foot board with the child's feet protruding through the bottom. It was found to be painted, with the decoration consisted of geometric patterns. A large anthropoid coffin decorated with offering bearers was excavated. Remnants of another painted wooden coffin were encountered in a thoroughly looted grave. Three unpainted coffins were uncovered, all were rectangular coffins for children. The most common wrapping consisted of strips of fabric wound around the body. The first example of a stela from the wadi mouth site was uncovered in this season. This area of the cemetery continued to have a uniform grave layout.[21]

Lower site: The burials uncovered contained single individuals and the graves had a uniform layout. Seven wooden coffins were encountered: five were plain and two were painted. Significantly, an anthropoid coffin made of mud for a child was excavated. One stela with a pointed top was found. No decoration survived.[22]

Middle site: 44 graves were identified and 32 were excavated, resulting in the recovery of 35 individuals. There was only one flexed burial, only the second in the cemetery. Two wooden coffins, both rectangular, were found. One was for a child and the other for an infant. Three examples of double burials were encountered: an infant and a child, and two cases of an adult women with a child. The second case was a woman and a baby buried at the same time. The baby was buried inside the matting, indicating that the pair were buried together, having possibly died in childbirth.[23]

Upper site: In 2012 six burials containing seven individuals were excavated. These were burials that had been identified but not excavated in the 2010 season. The excavation revealed 22 individuals buried in eight single burials, one double burial, and four triple burials. They were buried wrapped in textile, then rolled in matting made of differing materials. The graves were packed closely together.[24]

Wadi end site: Eight burials were excavated containing six adults and two children. One of the adults was elderly and noted as being buried with minimal care. Limestone fragments of possible burial cairns or grave lining were found.[25]

The end of the surface scatter was found to correspond fairly closely with the edge of the cemetery.[26]

The most common artefacts recovered were pottery fragments. The remains of food was recovered from some burials, most significantly pomegranates buried with a baby. Other significant finds included two bronze tweezers and two cosmetic applicators, jewellery including ear and hair rings, amulets depicting Taweret and Bes, a necklace of coloured faience beads beads and another of beads and fish pendants. A gold bracelet was found on the wrist of a baby.[27] The trend of high juvenile mortality continued, along with the high frequency of healed fractures and poor nutrition. Three men with healed piercing wounds to the scapula were encountered, along with a 13 year old with a skull fracture that was the likely cause of death. Amarna adults are the shortest reported for Ancient Egypt.[28]

External links

References

- Barry Kemp. "SOUTH TOMBS Cemetery". The Amarna Project. The Amarna Project. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Kemp, Barry; Rosa, Pamela (2003). "Fieldwork, 2002-03: Delta Survey, Memphis, Tell el-Amarna, Qasr Ibrim on JSTOR". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 89: 11.

- Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Bunbury, Judith; Nicholson, Paul T.; Kemp, Barry; Rose, Pamela (2005). "Fieldwork, 2004-05: Sais, Memphis, Saqqara Bronzes Project, Tell el-Amarna, Tell el-Amarna Glass Project, Qasr Ibrim". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 91: 22.

- Rowland, Joanne; Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Nicholson, Paul T.; Kemp, Barry; Parcak, Sarah; Rose, Pamela (2006). "Fieldwork, 2005–06". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92: 27–28.

- Kemp, Barry; Dabbs, Gretchen R.; Davis, Heidi S. (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 2–18.

- Rowland, Joanne; Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Nicholson, Paul T.; Kemp, Barry; Parcak, Sarah; Rose, Pamela; Rose, Jerome C. (2006). "Fieldwork, 2005–06". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92: 30–35.

- Rowland, Joanne; Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Nicholson, Paul T.; Kemp, Barry; Parcak, Sarah; Rose, Pamela; Rose, Jerome C. (2006). "Fieldwork, 2005–06". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92: 44–45.

- Rowland, Joanne; Wilson, Penelope; Jeffreys, David; Nicholson, Paul T.; Kemp, Barry; Parcak, Sarah; Rose, Pamela; Rose, Jerome C. (2006). "Fieldwork, 2005–06". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92: 37–38.

- Kemp, Barry; Dolling, Wendy (2007). "Tell El-Amarna, 2006-7". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 93: 11–35.

- Kemp, Barry; Dolling, Wendy (2008). "Tell El-Amarna, 2007-8". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 94: 13–41.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna (2009). "Tell El-Amarna, 2008-9". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 95: 11–27.

- Kemp, Barry; Shepperson, Mary (2009). "Tell El-Amarna, 2008-9". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 95: 21–27.

- Kemp, Barry; King Wetzel, M. (2010). "Tell El-Amarna, 2010". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 96: 1–7.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna (2010). "Tell El-Amarna, 2010". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 96: 10–21.

- Stevens, Anna; Rogge, Corina E.; Bos, Jolanda E. M. F.; Dabbs, Gretchen R. (2019). "From representation to reality: an ancient Egyptian wax head cones from Amarna" (PDF). Antiquity. 93 (372): 1515–1533. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Kemp, Barry; Shepperson, Mary (2010). "Tell El-Amarna, 2010". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 96: 7–10.

- Kemp, Barry; Zabecki, Melissa; Rose, Jerry (2010). "Tell El-Amarna, 2010". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 96: 28–29.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna (2012). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 98: 1–7.

- Kemp, Barry; Rose, Jerry; Dabbs, Gretchen R. (2012). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 98: 7–9.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna; Shepperson, Mary; King Weztel, Melinda (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 2–3.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna; Shepperson, Mary; King Weztel, Melinda (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 4–6.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna; Shepperson, Mary; King Weztel, Melinda (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 6–8.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna; Shepperson, Mary; King Weztel, Melinda (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 8–9.

- Kemp, Barry; Stevens, Anna; Shepperson, Mary; King Weztel, Melinda (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 9–12.

- Kemp, Barry; Dabbs, Gretchen R.; Davis, Heidi S. (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 12.

- Kemp, Barry; Dabbs, Gretchen R.; Davis, Heidi S. (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 12–13.

- Kemp, Barry; Dabbs, Gretchen R.; Davis, Heidi S. (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 13–14.

- Kemp, Barry; Dabbs, Gretchen R.; Davis, Heidi S. (2013). "Tell El-Amarna, 2011". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 16–18.