Ekasarana Dharma

Ekasarana Dharma[4] (Assamese এক শৰণ ধৰ্ম; literally: 'Shelter-in-One religion') is a Vaishanavite religion propagated by Srimanta Sankardeva in the 15th-16th century in the Indian state of Assam. It rejects vedic ritualism and focuses on devotion (bhakti) to Krishna in the form of congregational listening and singing his name and deeds (Kirtan) and (Sravan). It is also referred to as eka sarana hari naam dharma.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Assam |

|---|

|

|

Proto-historic

Classical Medieval

Modern |

|

|

|

Festivals

|

|

Religion Major

Others |

|

History

Archives

Genres

Institutions

Awards

|

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

|

Symbols

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Holy scriptures

|

|

Sampradayas

|

|

Related traditions |

|

|

The simple and accessible religion attracted already Hinduized as well as non-Hindu populations into its egalitarian fold. The neophytes continue to be inducted into the faith via an initiation ceremony called xoron-lowa (take-shelter or sarana), usually conducted by Mahantas who were heads of monastic institutions called Sattras who generally draw apostolic lineage from Sankardev. Some abbots, especially those from the Brahma-sanghati, reject apostolic lineage from Sankardev due to an early schism with the order. Some modern reformation institutions conduct xoron-lowa outside the sattra institution. Institutions propagating Eka Sarana like sattra (monasteries) and village Namghar (prayer houses), had profound influence in the evolution of the social makeup of Assam. The artistic creations emanating from this movement led to engendering of new forms of literature, music (Borgeets or songs celestial), theatre (Ankia Naat) and dance (Sattriya dance).

The central religious text of this religion is Bhagavat of Sankardeva, which was rendered from the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana by Srimanta Sankardeva and other luminaries of the Eka Sarana school. This book is supplemented by the two books of songs for congregational singing: Kirtan Ghoxa by Sankardeva and Naam Ghoxa by Madhabdev. These books are written in the Assamese language.

The religion is also called Mahapuruxiya because it is based on the worship of the Mahapurux or Mahapurush (Sanskrit: Maha: Supreme and purush: Being), an epithet of the supreme spiritual personality in the Bhagavata and its adherents are often called Mahapuruxia, Sankari etc. In course of time, the epithet 'Mahapurux' came also to be secondarily applied to Sankardeva and Madhabdev, the principal preceptors. Non-adherence to the Hindu varna system and rejection of Vedic karma marked its character.

Though often seen as a part of the wider, pan-Indian Bhakti movement, it does not worship Radha with Krishna which is common in other Vaishnava schools. It is characterised by the dasya form of worship. Historically, it has been against caste system, and especially against animal sacrifices common in other sects of Hinduism, especially Saktism. Noted for its egalitarianism, it posed a serious challenge to Brahminical Hinduism, and converted into its fold people of all castes, ethnicity and religion (including Islam).

Worshipful God and salvation

| Schools of Vedanta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Three Vaishnava schools accept the Bhagavata as authoritative (Madhava, Chaitanya and Vallabha)[5] whereas Ramanuja does not mention it.[6] Sankardev's school accepts the nirvisesa God[7] and avers on vivartavada[8] which maintains that the world is a phenomenal aspect of Brahma, thus taking it very close to Sankaracharya's position.[9] Further, like the modern neo-Vedanta philosophies, Sankardev's philosophy accepts both the Nirguna and the Saguna Brahma.[10] Despite this unique philosophical position among the Vaishnavites, the preceptors of Ekasarana or their later followers provided no commentary of the prasthana-traya or gloss and did not establish an independent system of philosophy.[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes, references and sources for table Notes and references

Sources

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The preceptors as well as later leaders of the Ekasarana religion focused mainly on the religious practice of bhakti and kept away from systematically expounding philosophical positions.[12] Nevertheless references found scattered in the voluminous works of Sankardeva and Madhavdeva indicate that their theosophical positions are rooted in the Bhagavata Purana[13] with a strong Advaita influence via its commentary Bhavartha-dipika by Sridhar Swami.[14] Nevertheless, Sankardeva's interpretation of these texts were seen at once to be "original and new".[15] Scholars hold that these texts are not followed in-toto and deviations are often seen in the writings especially when the original philosophical contents came into conflict with the primary focus of bhakti as enunciated in the Ekasarana-dharma.[16]

Nature of God

Though Ekasarana acknowledges the impersonal (nirguna) god, it identifies the personal (saguna) one as worshipful[17] which it identifies in the Bhagavad-Puranic Narayana.[18] The sole aspect that distinguishes the personal from the impersonal one is the act of creation,[19] by which Narayana created everything. Unlike in Gaudiya Vaishnavism it claims no distinction between Brahman, Paramatman and Bhagavat, which are considered in Ekasarana as just different appellations applied to the same supreme reality.[20]

Even though Narayana is sometimes used synonymously with Vishnu, the gods Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva are considered of lower divinity.[21]

Narayana as the personal and worshipful god is considered to be a loving and lovable god, who possesses auspicious attributes that attract devotees. He is non-dual, omnipotent and omniscient; creator, sustainer, and destroyer of all. He also possesses moral qualities like karunamaya (compassionate), dinabandhu (friend of the lowly), bhakta-vatsala (beloved of devotees) and patit-pavana (redeemer of sinners) that make him attractive to devotees. Though it does not deny the existence of other gods, it asserts that Narayana alone is worshipful and the others are strictly excluded.

Krishna

Following the Bhagavata Purana, the object of devotion in Ekasarana is Krishna, who is the supreme entity himself.[22][23] All other deities are subservient to Him.[24] Brahman, Vishnu and Krishna are fundamentally one.[25] Krishna is alone the supreme worshipful in the system. Sankaradeva's Krishna is Nārāyana, the Supreme Reality or Parama Brahma and not merely an avatara of Visnu. Krishna is God Himself.[26] It considers Narayana (Krishna) as both the cause as well as the effect of this creation,[27] and asserts Narayana alone is the sole reality.[28] From the philosophical angle, He is the Supreme Spirit (Param-Brahma). As the controller of the senses, the Yogis call him Paramatma. When connected with this world, He assumes the name of Bhagavanta.[29] Moreover, some of the characteristics usually reserved for the impersonal God in other philosophies are attributed to Narayana with reinterpretations.[30]

Jiva and salvation

The embodied self, called jiva or jivatma is identical to Narayana.[31] It is shrouded by maya and thus suffers from misery,[32] When the ego (ahamkara) is destroyed, the jiva can perceive himself as Brahma.[33] The jiva attains mukti (liberation) when the jiva is restored to its natural state (maya is removed). Though other Vaishnavites (Ramanuja, Nimbarka, Vallabha, Caitanya) recognise only videhamukti (mukti after death), the Ekasarana preceptors have recognised, in addition, jivanmukti (mukti during lifetime).[34] Among the five different kinds of videhamukti,[35] the Ekasarana rejects the Sayujya form of mukti, where the complete absorption in God deprives jiva of the sweetness and bliss associated with bhakti. Bhakti is thus not a means to mukti but an end to itself, and this is strongly emphasised in Ekasarana writings—Madhavdeva begins his Namaghosha with an obeisance to devotees who do not prefer mukti.[36]

Krishna is identical to Narayana

Narayana often manifests through avatars, and Krishna is considered as the most perfect one who is not a partial manifestation but Narayana himself.[37] It is in the form of Krishna that Narayana is usually worshiped. The description of Krishna is based on the one in Bhagavat Puran, as one who resides in Vaikuntha along with his devotees. Thus the worshipful form is different from other forms of Krishna-based religions (Radha-Krishna of Caitanya, Gopi-Krishna of Vallabhacharya, Rukmini-Krishna of Namadeva and Sita-Rama of Ramananda).[38] The form of devotion is infused with the dasya and balya bhava in the works of Sankardev and Madhabdev. Madhura bhava, so prevalent in the other religions, is singularly absent here.[39]

Four Principles

The cari vastu or the Four Principles defined this religious system are:

- Naam — the chanting and singing the name and the qualities of God. In general, only four names are most important: rama-krishna-narayana-hari)[40]

- Deva — worship of a single God, that is Krishna.[41]

- Guru — reverence of a Guru, or Spiritual Preceptor.[42]

- Bhakat — the association or the congregation of devotees (bhaktas)

Sankardev defined the first, second and fourth of these, whereas Madhavdev introduced the third while at Belaguri when he accepted Sankardev as the guru for himself and for all others who accepted his faith.[43] The four principles are revealed and their meaning explained at the time of initiation (xonron-lowa).

Four Books: sacred texts

The single most important religious text is the Bhagavata, especially the Book X (Daxama). This work was transcreated from the original Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana to Assamese in the 15th and 16th centuries by ten different individuals, but chiefly by Srimanta Sankardev who rendered as many as ten Cantos (complete and partial) of this holy text.

Three other works find a special place in this religion: Kirtan Ghoxa, composed by Sankardev; and Naam Ghoxa and Ratnavali, composed by Madhavdev.

Denominations

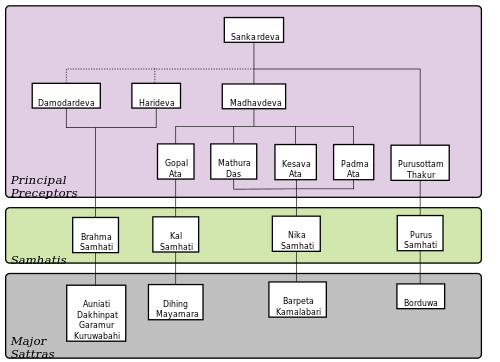

The religion fissured into four sanghati (samhatis or sub-sects) soon after the death of Srimanta Sankardeva. Sankardev handed down the leadership to Madhabdev, but the followers of Damodardev and Harideva did not accept Madhabdev as their leader and formed their own group (Brahma sanghati). Madhabdeva at the time of his death did not name a successor. After his death three leaders formed their own denominations: Bhabanipuria Gopal Ata (Kaal sanghati), Purushuttom Thakur Ata, a grandson of Sankardev (Purusa sanghati) and Mathuradas Burhagopal Ata (Nika Sanghati). They differ mostly in the emphasis of the cari vastus (four fundamental principles)

Brahma sanghati

The Brahma sanghati developed as a result of Damodardev and Haridev moving away from Sankardev's successor Madhabdev's leadership. Over time this sanghati brought back some elements of Brahminical orthodoxy. The vedic rituals which are generally prohibited in the other sanghatis are allowed in this sanghati. Brahmins too found this sanghati attractive and most of the Sattras of this sanghati have traditionally had Brahmin sattradhikars. Among the cari vastus, Deva is emphasised, worship of the images of the deva (Vishnu and the chief incarnations, Krishna and Rama) are allowed. Among the gurus Damodardev is paramount. Later on they came to call themselves Damodariya after Damodardev.

Purush sanghati

The Purush sanghati was initiated by the grandsons of Sankardeva—Purushottam Thakur and Chaturbhuj Thakur—after the death of Madhavdev. The emphasis is on Naam. Sankardeva has a special position among the hierarchy of Gurus. Some brahminical rites as well as the worship of images is tolerated to some extent.

Nika sanghati

This sanghati was initiated by Padma, Mathuradas and Kesava Ata. The emphasis is on sat-sanga. This sanghati is called Nika (clean) because it developed strict codes for purity and cleanliness in religious matters as well as in general living, as laid down by Madhabdeva. Idol worship is strictly prohibited and it gives special importance to Madhavdev.

Kala sanghati

The Kala sanghati, initiated by Gopal Ata (Gopalldev of Bhavanipur) and named after the place of his headquarters Kaljar, placed its emphasis on Guru. The sattariya of this sanghati came to be considered as the physical embodiment of Deva, and the disciples of this sect are not allowed to pay obeisance to anyone else. This sect was successful in initiating many tribal and socially backward groups into the Mahapuruxia fold, and it had the largest following among the different sanghatis. The Dihing sattra, one of the large sattra's received royal patronage; but the largest sattra, Moamara, forged an independent path and the followers of this sect were responsible for the Moamoria rebellion against the Ahom royalty.[44]

See also

Notes

- "639 Identifier Documentation: aho – ISO 639-3". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). SIL International. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

Ahom [aho]

- "Population by Religious Communities". Census India – 2001. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Census Data Finder/C Series/Population by Religious Communities

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- Sarma (Sarma 1966, p. 41), Cantlie (Cantlie 1984:258) and Barman (Barman 1999:64) call it Ekasarana. Maheshwar Neog uses both Ekasarana(Neog 1985:111) as well as Ekasarana naam-dharma, qualifying the word dharma in the second example. Others call it Ekasarana Hari-naam-Dharma, further qualifying the word dharma.

- (Sheridan 1986, p. 2)

- (Sheridan 1986, p. 7)

- "To him (Sankardev) Brahman is indeterminate (nirvisesa)..." (Neog 1981, p. 244)

- "Sankardev cannot lend himself to parinamavada because of his monistic position and therefore, leans on the side of vivartavada (Neog 1981, p. 227)

- "...on the philosophical or theoretical side there is scarcely any difference between the two Sankaras. (Neog 1981, p. 244)

- (Sarma 1966, p. 27)

- (Neog 1981, p. 223)

- Though several schools of Vaishnavism had their own philosophical treatises (Ramanuja, Madhava, Nimbarka, Vallabhacharya), Sankardeva and Chaitanya did not. Though Jiva Goswami compiled systematic works for Chaitanya, nothing similar was attempted by Sankardeva's followers (Neog 1980, pp. 222–223)

- "Sankaradeva was enabled to preach the new faith he had established for himself and for earnest seekers in his province, basing it on the philosophical doctrines of the Gita and the Bhagavata Purana as its scriptures" Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. "The Eka-sarana Dharma of Sankaradeva: The Greatest Expression of Assamese Spiritual Outlook" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "...the influence of the Bhagavata Purana in forming the theological backbone of Assam Vaishnavism in quite clear and the monistic commentary of Sridhara Swami is highly popular amongst all sections of Vaishnavas" (Sarma 1966, p. 26)

- "If there could be any question of mutation or affiliation still, it could have been with the Gita and the Bhagawat direct which Sankardew read and interpreted in his own way, at once original and new" (Neog 1963, p. 4). Haladhar Bhuyan, the founder of the Sankar Sangha, a modern sect of Ekasarana concurs: "Sri Neog now definitely shows that Sankardew’s philosophy is his own and that his religion is as original as that of any great preacher of the world" (Neog 1963:vii)

- For example, "the Chapters of the Bhagavata Purana, where the Pancharatra theology is discussed, have been omitted by Assamese translators because the Vyuha doctrine finds no place in the theology of Assamese Vaishnavism." (Sarma 1966, p. 27); "the highly philosophical benedictory verse (mangalacarana) of Book I of the Bhagavata-Purana, which has been elaborately commented upon by Sridhara from the monistic stand-point, has been totally omitted by Sankaradeva in his rendering." Whereas, "Kapila of Saṃkhya is an incarnation of God" in the original, Saṃkhya and Yoga are made subservient to bhakti (Neog 1980, p. 235). Furthermore, "Where Sridhara's commentary appears to them in direct conflict with their Ekasarana-dharma, they have not hesitated to deviate from Sridhara's views." (Sarma 1966, p. 48)

- "Assamese Vaishnava scriptures without denying the nirguna, i.e. indeterminate aspect of God, have laid more stress on the saguna aspect." (Sarma 1966, p. 27).

- "The first two lines of Kirtana has struck this note: 'At the very outset, I bow to the eternal Brahman who in the form of Narayana is the root of all incarnations'" (Sarma 1966, p. 27)

- Nimi-nava-siddha-sambad, verses 187–188 (Sarma 1966, p. 27)

- ekerese tini nama laksana bhedata in Nimi-navasiddha-sambada verses 178–181 (Sankardeva) (Sarma 1966, p. 30)

- Nimi-navasiddha-samvada, verse 178 (Sankardeva); Anadi-patan verses 163–167 (Sankardeva) (Sarma 1966, p. 31)

- Chutiya, Sonaram. "Srimad-Bhāgavata : The Image of God" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- Bezbaroa, Lakshminath (2004). A Creative Vision: – Essays on Sankaradeva and Neo-Vaisnava Movement in Assam (PDF). Srimanta Sankar Kristi Bikash Samiti. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

Krishna was the all-supreme God of adoration for him

- "Fundamental Aspects of Sankaradeva's Religion – Monotheism". Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- Chutiya, Sonaram. "The Real Philosophy of Mahāpurusism" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Fundamental Aspects of Sankaradeva's Religion – Monotheism". Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- Kirtana VIII (Sarma 1966, p. 29)

- Bhakti-ratnakar, verse 111 (Sarma 1966, p. 29)

- Gupta, Bina. "Lord Krishna's Teachings and Sankaradeva". Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- For example, nirakara is used to describe Narayana as someone without an ordinary or special form (prakrita akara varjita) (Sarma 1966, p. 28)

- "Though associated with body yet I am not identical with it: I am verily Paramatma. I am Brahma and Brahma is I", Sankardeva in Bhagavata Book XII verses 18512-18518 (Sarma 1966, p. 33)

- Sankardeva, Bhakti-ratnakara, verse 773 (Sarma 1966, p. 35)

- Sankardeva, Bhagavata (Sarma 1966, p. 34)

- (Sarma 1966, p. 41)

- (1) Salokyo (being in the same plane as God); (2) Samipya (nearness to God); (3) Sarupya (likeness to God); (4) Sarsti (equaling God in glory) and (5) Sayujya (absorption in God)

- (Sarma 1966, pp. 41–42)

- based on the Bhagavata Puran, 1/3/28 (Sarma 1966, p. 32)

- (Murthy 1973, p. 233)

- (Sarma 1966, p. 32)

- (Neog 1980:348)

- (Neog 1980:347-348)

- At the time of xoron-lowa both Sankardev and Madhavdev are mentioned as the original gurus of the Order, though Sankardev is very often considered alone. (Neog 1980:349-350)

- (Neog 1980:346)

- (Neog 1980:155)

References

- Cantlie, Audrey (1984). The Assamese. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barman, Sivanath (1999). An Unsung Colossus: An Introduction to the Life and Works of Sankaradeva. Guwahati.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neog, Dimbeswar (1963). Jagat-Guru Sankardew. Nowgong: Haladhar Bhuya.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neog, Maheshwar (1980). Early History of the Vaishnava Faith and Movement in Assam. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, S N (1966). The Neo-Vaisnavite Movement and the Satra Institution of Assam. Gauhati University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murthy, H V Sreenivasa (1973). Vaisnavism of Samkaradeva and Ramanuja (A Comparative Study). Motilal Banarsidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheridan, Daniel (1986). The Advaitic Theism of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Retrieved 12 December 2012.